The Auburn, Cord, and Duesenberg Museum is somewhat misleadingly named. Yes, they have a stunning and visually arresting collection of Auburns, Cords, and Duesenbergs (one of the best I’ve ever seen), but the collection of more than 120 vintage automobiles includes more than just these three marques. There’s even a vintage BSA motorcycle (I’ll get to that in a bit).

The Museum is housed in what used to be the Auburn factory. It’s in Auburn, Indiana, where they used to make Auburn automobiles. Auburn is north of Indianapolis (the quick way in is on Interstate 69); we stopped there on our way to Goshen to visit the Janus factory. Janus was fun and I grabbed a ton of awesome photos there, too. Grab the September/October issue of Motorcycle Classics magazine and you’ll see it. But that’s not what this blog is about. Let’s get back to Auburn and the Museum.

The Museum is magnificent and the automobiles are stunning. The Duesenbergs are beyond stunning but don’t take my word for it. You might consider seeing this magnificent collection yourself. I took enough photos to fill a book and I had a hard time picking just a few to show here. I probably went a little overboard, but the cars are so nice it was hard not to.

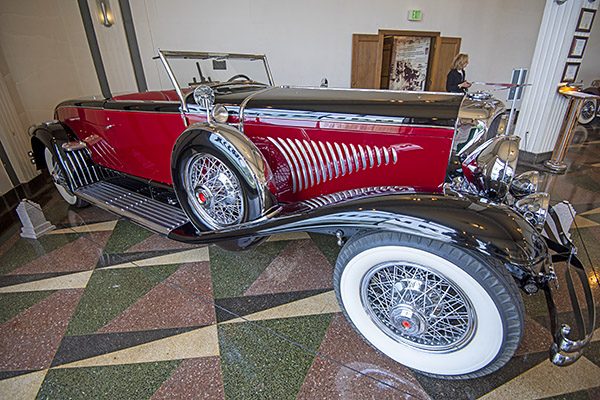

Here’s a 1931 Duesenberg Model J. The body was built by the Murphy company of Pasadena, who made more Duesenberg bodies than any other company. The car has a straight 8 engine.

This is a V-16 Cadillac, another truly magnificent automobile.

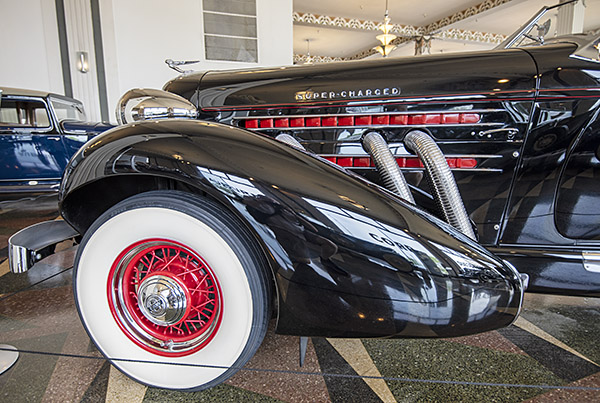

Next up is a supercharged 1935 Auburn. It is an 851 Speedster, with a Lycoming straight 8 engine. It cost $2,245 when it was new (less than a used Sportster, if you’re using that as a benchmark). The lines on this car are beautiful, and the colors work, too.

This next car is a 1929 Ruxton, a car I had never heard of before visting the Auburn Cord Duesenberg Museum. It’s a front-wheel-drive car, a competitor to the Cord in its day. According to what I found online, the Ruxton was lower, lighter, and handled better than the Cord. The looks and the colors work for me.

Check out the Ruxton’s headlights. These are Woodlite headlights, which are very art deco. They look like helmets.

Here are two 1937 Cord 812 automobiles: A convertible and a coupe. The colors and the style are impressive. When I was a kid, I built a Monogram plastic model of a Cord that I think was based on the convertible I saw in Indiana.

Here are two 1937 Cord 812 automobiles: A convertible and a coupe. The colors and the style are impressive. When I was a kid, I built a Monogram plastic model of a Cord that I think was based on the convertible I saw in Indiana.

Here’s a 1948 Lincoln Continental Coupe with a V-12 engine. 1948 was the last year any US automobile manufacturer made a V-12. This one had 305 cubic inches and it produced 130 horsepower. The car you see here cost $4,145 in 1948.

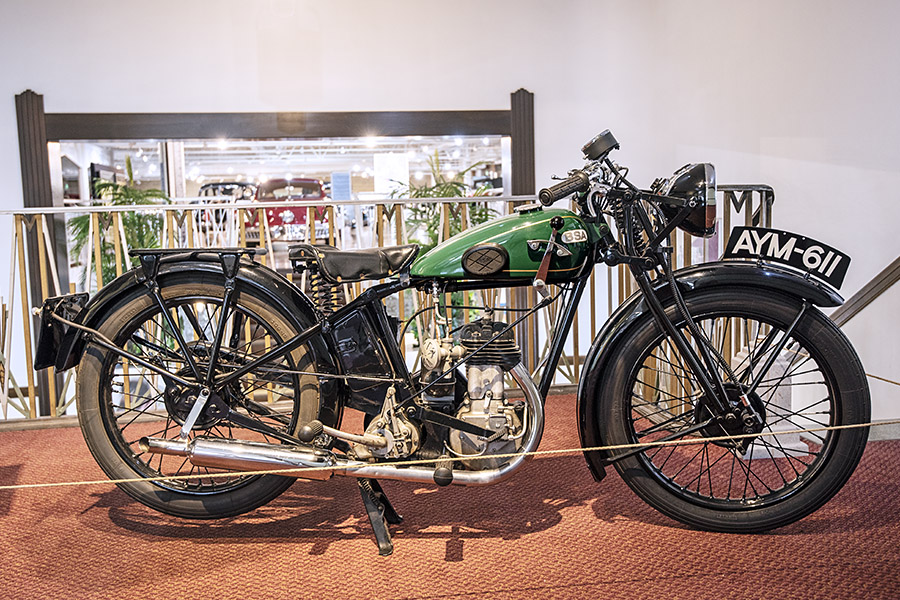

This 1933 250cc single-cylinder BSA is the lone motorcycle in the Cord Auburn Duesenberg Museum. This one was E.L. Cord’s personal motorcycle, which he kept on his yacht and at his Nevada ranch.

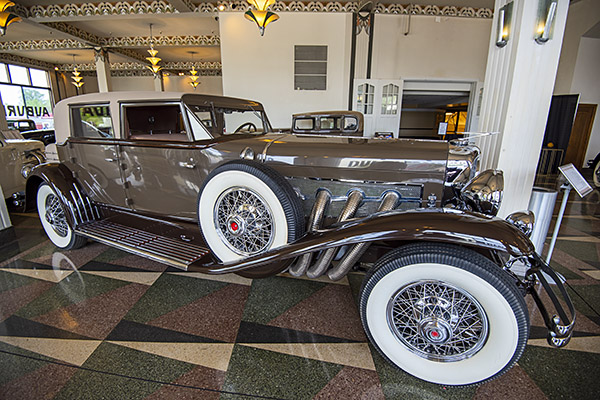

Another magnificent Duesenberg. This one is a 1931 Beverly sedan, with a 420 cubic inch, straight 8, 265-horsepower engine It went for $16,500 when it was new.

This is an XK 120 Jaguar. I think this is one of the most beautiful cars ever made. It’s my dream car, in exactly these colors.

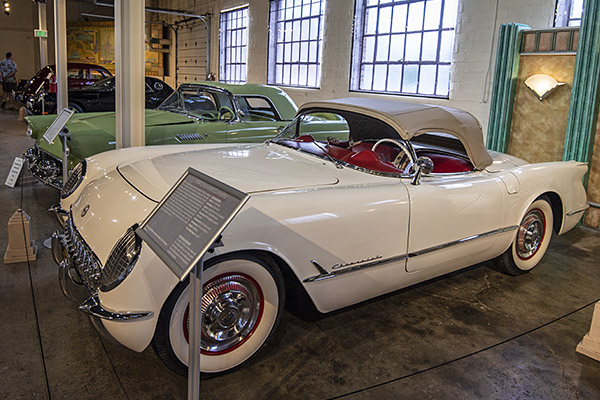

Here’s a first-year-of-production, 1953 Corvette. Chevy introduced the Corvette in the middle of the 1953 model year, so there were only a few made. The 1954 Corvette was essentially the same car.

Chevy was going to discontinue the Corvette due to its low sales, but the dealers convinced them otherwise. The dealers didn’t sell a lot of Corvettes, but they sold a lot of other Chevys to people who visited the showrooms to see the Corvette.

Another view of the first year Corvette. Note the mesh headlight protectors.

Ford’s answer to the Corvette…the two-seat Thunderbird. The little T-Bird never matched the Corvette’s performance. After three years of production (1955 to 1957), Ford redesigned the Thunderbird as a larger four-seater.

The Thunderbird soldiered on as a four-seater for years, then it was discontinued, then it briefly emerged again as a two-seater in 2002 (that’s the car you see below). The new Thunderbird only lasted through 2005, and like the classic ’55/’56/’57 two-seat T-Birds, Ford dropped this one, too. My buddy Paul drives one that looks exactly like this.

Auburn is a cool little town. Its population is about 14,000 and the town is about 145 miles north of Indianapolis (it’s a straight shot up on Interstate 69). The town is rooted in automotive history, and other history as well. In 1933, John Dillinger and his gang raided the local police station and they stole several firearms and ammunition. But it’s the automobiles and their history that make this town a worthy destination. Auburn, Indiana, loves its automobiles and automotive history. We saw several vintage cars being used as daily drivers. The murals were cool, too.

You can easily spend three or four hours in the Auburn Cord Duesenberg Museum, and spending the entire day there wouldn’t be out of the question. One of Auburn’s best kept dining secrets is Sandra D’s, a reasonably-priced Italian restaurant with an exquisite menu. Try the eggplant parmesan; you won’t be disappointed.

Hit those popup ads!

Never miss an ExNotes blog: