California’s 10 days are up, and Henry is in the house!

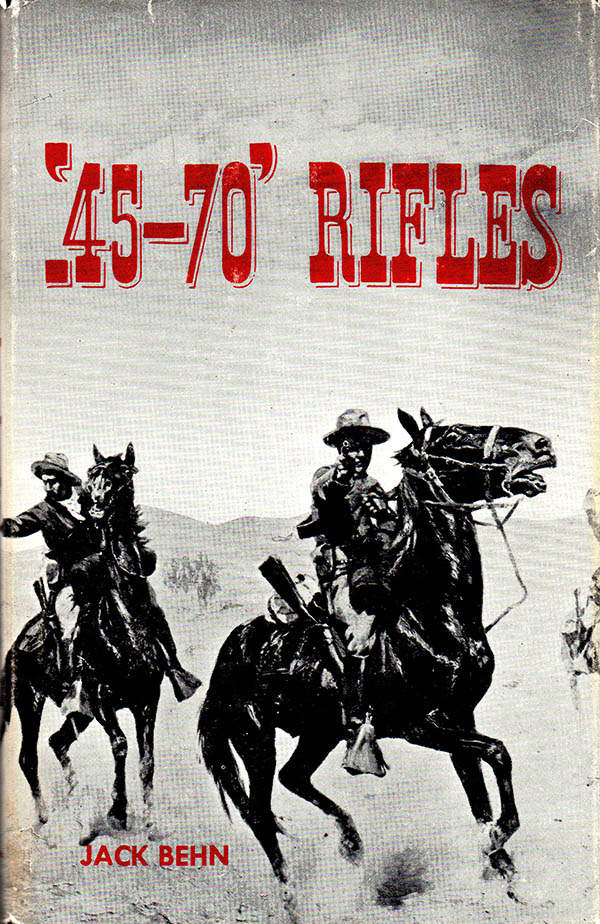

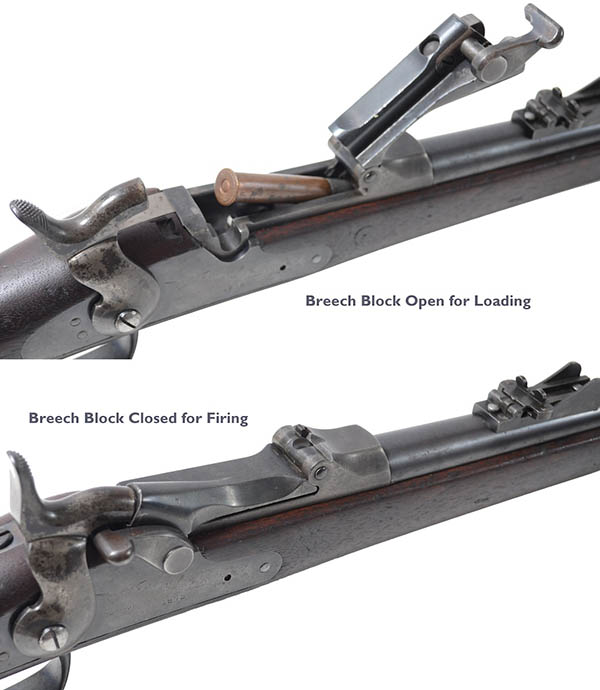

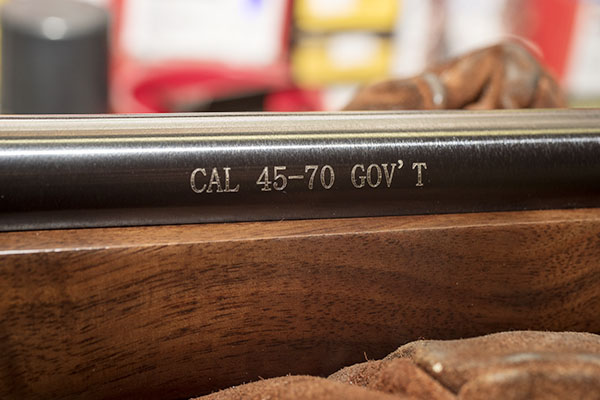

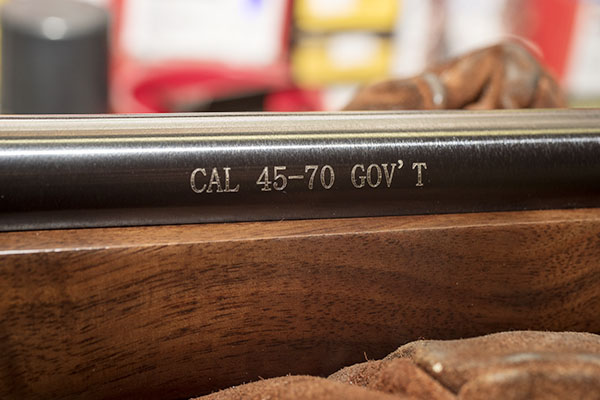

Henry, of course, is my new brass-framed .45 70 Single Shot from the rifle manufacturer of the same name. I haven’t shot it yet, but I’m ready. Eager, too. This is going to be fun.

To continue the story and as promised, a few days ago I interviewed Daniel Clayton-Luce, Henry’s Director of Communications. As you know from reading our earlier blogs, I am impressed with Henry and I purchased one of their new Single Shot rifles. I picked up my Single Shot yesterday (practicing all the required social distancing rules, of course), and wow, it is one fine firearm. Take a look.

With me, it’s always been about the wood. I’ll get better photos when I’m basking in the grand and glorious sunshine at the West End Gun Club (and I’m not sure just yet when that will be), but here are a few teaser shots.

Like I said above, I haven’t shot the Henry yet. But my first impressions are very, very good. The wood is stellar (both the stock and the fore end), the wood-to-metal fit is way better than what I’m used to seeing on production guns, the action feels crisp and tight, and the brass frame and buttplate are classy. The trigger is a little heavy, but it is breaking-glass crisp, and the rifle shoulders well. The quality is off the charts. It’s that good.

So, about that interview with good buddy Dan from Henry USA…let’s get to it. My first questions were these: What prompted Henry to enter the single shot rifle market, and did Henry do so by purchasing the old Harrington and Richardson design and production equipment?

Dan explained to me that the new Henry Single Shot is a Henry through and through, it has no relation to the H&R design, and I would absolutely notice a difference in quality between it and the H&R guns. He sure was right. I am a collector and admirer of fine rifles (I’ve focused primarily on Ruger No. 1 and Ruger No. 3 rifles), and I think I know a bit about what goes into a good rifle. For me, the Ruger No. 1 has been the gold standard, especially the earlier ones made in the late 1960s and 1970s. I’m here to tell you that the new Henry is equal to those rifles, and perhaps even better. The fit, the finish, the wood, the bluing, and the overall feel of my Henry is absolutely top notch. Surprisingly, the new Henry brass-framed .45 70 (at an MSRP of a little over $600) is less than half the cost of a new Ruger No. 1. I am impressed. Dan told me that Henry decided to enter the single shot market with a premium offering, and after examining my new rifle, I can tell you that “premium” is the right adjective. My Henry Single Shot is stunning.

I told Dan that I thought entering the single shot rifle market had to be a risky venture (H&R went out of business, Ruger’s No. 1 sales have declined significantly, and the rage today seems to be black plastic Rambo wannabee guns). Dan told me that bringing the Henry Single Shot to market wasn’t as dicey a proposition as it might appear. Henry USA felt there was a strong desire in many shooters to get back to the basics, and shooting doesn’t get more basic than only having one shot. You need to make that one shot count, Dan said, and there’s an inherent challenge that makes a successful hunt with a single shot rifle more rewarding. It forces you to slow down, take your time with each shot, and think about the fundamentals. Dan didn’t have to convince me. I knew exactly what he was talking about. My first rifle was a single shot and I’ve been addicted to them ever since.

Dan told me the Henry Single Shot is doing well. Sales are good, and the rifle is a flexible platform (it is easy to introduce new calibers). In viewing the Henry USA website, I saw that the Single Shot is offered in .223, .243, .30 30, .308 Winchester, .357 Magnum, .44 Magnum, and .45 70. They have shotgun versions, too, in .410, 20 gauge, and 12 gauge. I suggested that Henry consider adding .22 Hornet to the mix (the .22 Hornet is a classic cartridge and it is one of my favorites, as you know from our earlier blogs on the Ruger No. 3 and my vintage Winchester Model 43). Dan said they would take a look at that and I immediately put my oar in the water…I told Dan when they bring out a .22 Hornet I want the first one off the production line (with fancy walnut, of course).

I asked Dan if they were going to offer replacement barrels to allow changing from one caliber to another. There are no plans to do so, he told me, and I can see the logic in that. Henry offers two models of the Single Shot rifle, one with a brass frame and one with a steel frame. The brass frame models are offered in chamberings that operate at lower pressure (.45 70, .357 Magnum, and .44 Magnum). If the barrels were interchangeable, there’s a risk someone might mount the barrel for a higher-pressure cartridge (e.g., .308 Winchester) on a brass frame. I get it.

I asked about folks using Henry rifles in competition, and Dan told me they are popular in both SASS (Single Action Shooting Society) and cowboy silhouette. There are no kits on the market for slicking the actions on a Henry lever gun (as exist for Marlin rifles), but the Henry rifles still have a good presence in these events.

Henry’s website says that Henry is the leading lever action manufacturer. Dan said that’s true, both from the perspective of quantity of rifles and sales revenue. That’s impressive. Marlin and Winchester have been around for more than 150 years, and Henry has already surpassed them,

My next question was on takedown and cleaning. I’ve owned Marlin and Winchester lever guns, and the difference in disassembling the two for cleaning is significant. On the Marlin, you only have to remove one screw (the lever pivot screw), and then the lever, the bolt, and the ejector are easily removed to provide access to the breech. Disassembling a Winchester is much more complex. Dan told me the Henry lever guns are like Marlins in that regard. That’s a good thing. On that same topic, I spent some time looking at Henry’s web-based maintenance videos. As a guy who’s done a few of those for CSC Motorcycles (I know what it takes to make a good video), I was impressed. The Henry videos are excellent. They cover disassembly, reassembly, sight adjustment, cleaning, and more. This is good stuff.

Anthony Imperato is Henry’s President and CEO (that’s Mr. Imperato you see in the photo above). In the video on the Henry website he comes across as a cool guy, so I asked the question: What’s he really like? Dan told me that Anthony is a personable, good-natured, hands-on leader and a genuine nice guy. He’s a shooter, too. That was good to hear. When I work with the best motorcycle companies (like CSC or Janus), it’s always good to see that the top people are riders as well as business leaders. Dan told me that the overwhelming majority of the nearly 500 employees at Henry are shooters and hunters. It sounds like a team I would like to join. If I was younger and looking for a place to make a difference, I’d send a resume to Henry.

Henry USA started as a small manufacturing operation in Brooklyn, New York. Henry outgrew the Brooklyn facility and moved manufacturing to Bayonne, New Jersey. In 2016, Henry opened a second plant in Rice Lake, Wisconsin to manufacture the Single Shot. Henry has grown to nearly 500 employees and they now offer a wide range of rifles, shotguns, and accessories. Take it from me, folks: Henry is the real deal, a genuine Made-In-America success story.

I asked Dan about the make/buy mix on their guns, and he told me 100% of the parts in a Henry are made in the U.S. The walnut comes from Missouri and is finished in North Carolina. There must be something about the soil and the water in Missouri; all the best wood from custom riflesmiths comes from Missouri. And North Carolina has a long heritage of making high end furniture, so it’s a natural fit for those good Southerners to craft the Missouri walnut for Henry. Henry uses a spray varnish on all but their modern version of the original Henry rifle (those rifles have an oil finish). I examined my Henry carefully, and the finish is flawless. I’m pretty picky about that sort of thing, having finished a few rifles myself. These folks have it wired. Henry does its own machining, too, including the barrels.

Dan and I spoke about their different models for a bit, and I asked which one is the most popular. The best-selling of all the Henry rifles is their H001, the .22 lever action rifle. In the Single Shot series, it’s the .45 70 (I guess great minds work alike). Dan told me every Henry has a lifetime warranty that follows the gun. New, used, or inherited, Henry stands behind the rifle for life. That says a lot. Henry tests every rifle for safety and functionality. They don’t test for accuracy, but they don’t need to. I know from firing good buddy TK’s beautiful brass-framed .44 Mag Henry lever gun that they are very accurate. When TK let me shoot his .44, I put five slugs through a hole you could cover with a quarter. In fact, it was that morning on the range a few years ago with TK that first planted the Henry seed in my mind.

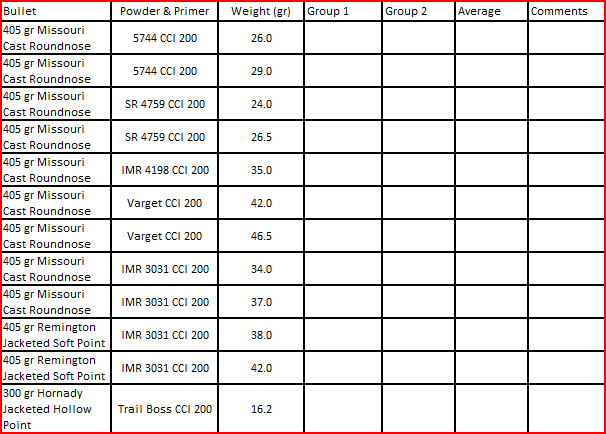

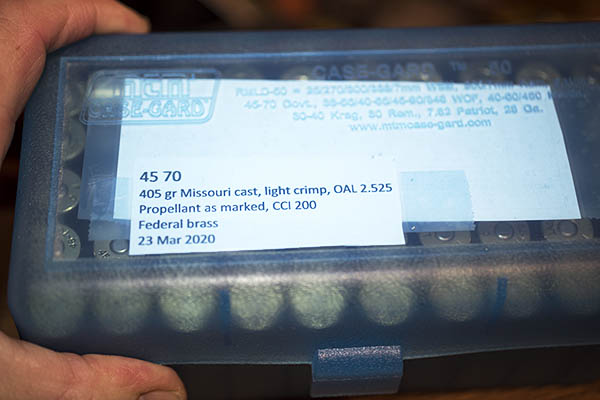

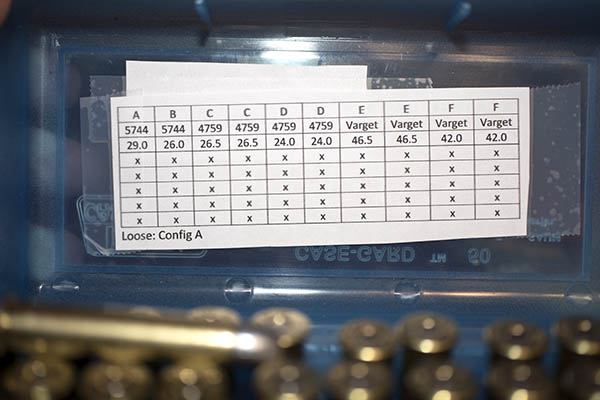

I was going to ask Dan why someone would buy a Henry instead of a Marlin, a Winchester, or a Ruger, but I already knew the answer. It’s for all the reasons you see above. Good walnut, classy looks, a good trigger, real craftsmanship, a great price, accuracy, a lifetime warranty, and it’s all made right here in the USA. It just doesn’t get any better than this. The Henry .45 70 Single Shot is a beautiful and handy carbine that looks and feels the way a gun should. It’s 7 pounds and .45 70 chambering will make for a bit of kick on the bench with the 405-grain Missouri bullets, but that’s okay. On a hunt, I’ve never felt the recoil or even heard the gun fire when the hammer drops. That’s what intense concentration does; you folks who have experienced it already know that. The look? Henry nailed it. There’s something about polished brass, blue steel, and fancy walnut that simply feels right on a fine firearm, and Henry has made this a fine firearm indeed.

Stay tuned to the ExhaustNotes blog for the .45 70 Henry range test. Sign up here and never miss an ExhaustNotes blog!

Check out our earlier Henry Single Shot stories here:

Developing a Henry .45 70 Load: Part 2

Developing A Henry .45 70 Load: Part 1

The Henry Is In California

Henry Rifles: Made in America Or Not Made At All

Want more gun stuff? Hey, just click here!

Would you like to know more about Henry USA? Here you go, folks!

You guys and gals will remember my good buddy Mike, whom I met on one of the CSC Baja runs a couple of years ago. It was a chance meeting…we stopped to buy bottled gas from one of the roadside entrepreneurs in Catavina and I noticed one of the bikes had a set of jump wings on the tail box. We had been on the road a few days already and I wondered why I hadn’t noticed the Airborne insignia before, and then I realized it was because I hadn’t noticed the bike was a BMW GS, not a CSC RX3 (that’s how much the bikes look alike, I guess). I looked around and there was Mike (a new face in the crowd), waiting for fuel just like the rest of us. You meet the coolest people in Baja, and you meet the coolest people on motorcycles. I liked Mike immediately.

You guys and gals will remember my good buddy Mike, whom I met on one of the CSC Baja runs a couple of years ago. It was a chance meeting…we stopped to buy bottled gas from one of the roadside entrepreneurs in Catavina and I noticed one of the bikes had a set of jump wings on the tail box. We had been on the road a few days already and I wondered why I hadn’t noticed the Airborne insignia before, and then I realized it was because I hadn’t noticed the bike was a BMW GS, not a CSC RX3 (that’s how much the bikes look alike, I guess). I looked around and there was Mike (a new face in the crowd), waiting for fuel just like the rest of us. You meet the coolest people in Baja, and you meet the coolest people on motorcycles. I liked Mike immediately. The trip started out great in San Felipe in a wonderful off grid solar AirBnb casita, with a lovely host (we only travel Saturday and Sunday as we are heads down working Mon-Fri in AirBnBs). We continued camping, riding, and staying in AirBnBs all through Guerro Negro, Muleje, La Ventana, Todo Santos, and Loreto. We were spending a week in each location to fully absorb the unique cities, people, and culture while soaking up the incredible desert roads, ocean views, and all while meeting new riders that will become lifelong friends along the way.

The trip started out great in San Felipe in a wonderful off grid solar AirBnb casita, with a lovely host (we only travel Saturday and Sunday as we are heads down working Mon-Fri in AirBnBs). We continued camping, riding, and staying in AirBnBs all through Guerro Negro, Muleje, La Ventana, Todo Santos, and Loreto. We were spending a week in each location to fully absorb the unique cities, people, and culture while soaking up the incredible desert roads, ocean views, and all while meeting new riders that will become lifelong friends along the way.