It was one of the things my 10th grade English teacher drilled into us, although in my case it didn’t take too well. I always alliterate at every opportunity, and I always appreciate it when others similarly sin. That’s why this video, which I noticed in my Facebook feed (oops, uh oh, and all that…I did it again) was immediately appealing. Stetsons, Steers, and Lone Stars…who could refuse to review such a stunningly-subtitled YouTube?

Month: November 2018

Zed’s Not Dead: Part 12

When I took off Zed’s rear wheel I noticed two spacers on the brake drum side. This isn’t very Kawasaki-like and I suspect it was assembled wrong. The long spacer probably goes on the drum side with the short spacer keeping the sprocket side from rubbing against the chain adjusters. I’ll try it and check alignment.

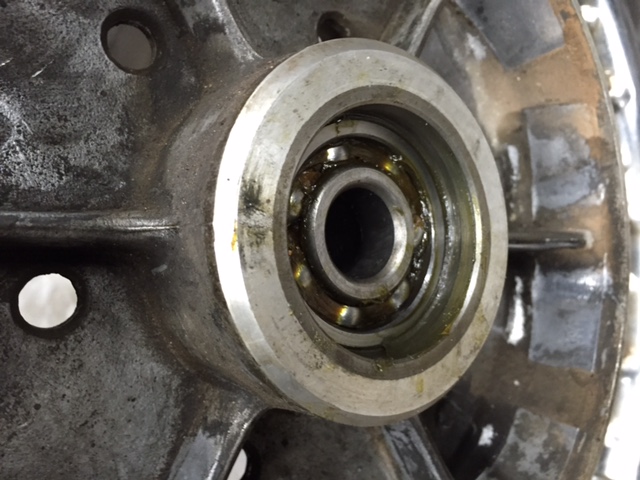

While I’m busting a new tire onto Zed I figured I might as well replace the rear wheel bearings. I could have cleaned them and re-greased them and if I was broke I would have. Z1 Enterprises carries the All Balls brand and they have fit well wherever else I’ve used the brand. I stick with what works. I don’t like change.

While I’m busting a new tire onto Zed I figured I might as well replace the rear wheel bearings. I could have cleaned them and re-greased them and if I was broke I would have. Z1 Enterprises carries the All Balls brand and they have fit well wherever else I’ve used the brand. I stick with what works. I don’t like change.

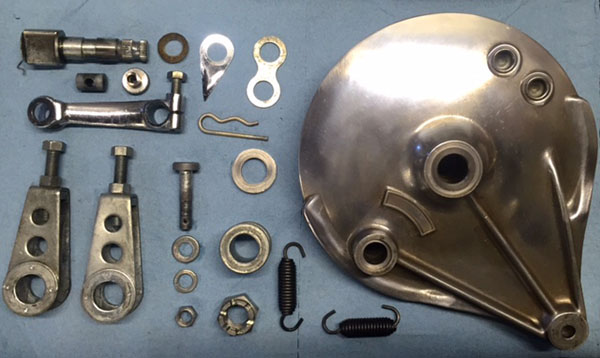

Kawasaki made a nice motorcycle when they built the Z1. Stuff like a brake shoe wear indicator was rare back in the 1970’s. Mama K even went to the trouble of recessing the brake shaft opening to fit a felt dust seal. That’s class, man. I’m not sure it does any good because the brake shoes generate more dust than you’d get kicked up from the street. Maybe it helps the shaft grease stay clean.

Kawasaki made a nice motorcycle when they built the Z1. Stuff like a brake shoe wear indicator was rare back in the 1970’s. Mama K even went to the trouble of recessing the brake shaft opening to fit a felt dust seal. That’s class, man. I’m not sure it does any good because the brake shoes generate more dust than you’d get kicked up from the street. Maybe it helps the shaft grease stay clean.

Kawasaki threw everything at the Z1. The sprocket carrier has its own bearing so that gives a total of three rear wheel bearings. Pretty sweet; I wish my Yamaha 360 had a better sprocket carrier design. The hub wears out and I have to feed spring-steel from a ¾-inch tape measure to take up the slack.

Kawasaki threw everything at the Z1. The sprocket carrier has its own bearing so that gives a total of three rear wheel bearings. Pretty sweet; I wish my Yamaha 360 had a better sprocket carrier design. The hub wears out and I have to feed spring-steel from a ¾-inch tape measure to take up the slack.

Part of the fun of working on motorcycles is setting up the exploded parts shot. I like to get all the parts clean before reassembly because they will never be cleaned again. Rear discs are mostly standard now but a husky rear drum like this will stop a bike just fine.

Part of the fun of working on motorcycles is setting up the exploded parts shot. I like to get all the parts clean before reassembly because they will never be cleaned again. Rear discs are mostly standard now but a husky rear drum like this will stop a bike just fine.

Changing tires is a lot of stress for me. If you don’t plan to use the tube or tire you can cut the work involved in half by cutting the old tire off. Use a razor, utility knife and lube the blade with a little oil. Then plunge in and pull the knife. Don’t saw at it. As you cut move around a little and you will find the thinnest part of the tire. Once you’re there, ride that sucker all the way around. After you do both sides the tread falls away leaving two beads. They pop off easy with no tire to create resistance and you can peel the remains off the rims without a tire iron.

Changing tires is a lot of stress for me. If you don’t plan to use the tube or tire you can cut the work involved in half by cutting the old tire off. Use a razor, utility knife and lube the blade with a little oil. Then plunge in and pull the knife. Don’t saw at it. As you cut move around a little and you will find the thinnest part of the tire. Once you’re there, ride that sucker all the way around. After you do both sides the tread falls away leaving two beads. They pop off easy with no tire to create resistance and you can peel the remains off the rims without a tire iron.

I removed the swingarm to check the bushings and lube the mess. Zed’s battery box is pretty rusty so I removed it to clean and paint the thing. I looked at the rear of the bike and decided there wasn’t much more to take everything off and give the rusty frame tubes a lick of paint. So I did.

I removed the swingarm to check the bushings and lube the mess. Zed’s battery box is pretty rusty so I removed it to clean and paint the thing. I looked at the rear of the bike and decided there wasn’t much more to take everything off and give the rusty frame tubes a lick of paint. So I did.

Reassembling the rear of the bike is going well and the Z1 Enterprises rear fender wiring harness fit perfectly. The original blinker stalks are slightly bent back. I’m going to leave them as they are. It gives the illusion of speed.

Reassembling the rear of the bike is going well and the Z1 Enterprises rear fender wiring harness fit perfectly. The original blinker stalks are slightly bent back. I’m going to leave them as they are. It gives the illusion of speed.

Almost time to make another parts order. I can get a seat cover or an entire new seat from Z1 Enterprises. Maybe Santa will drop one down the chimney.

Zed is coming along! Read the rest of the Zed’s Not Dead series here!

A bad influence?

I may be that kid your mother always warned you about. You know, the bad influence. The one who might do something she wouldn’t like, and then you follow suit. Moms live in fear of guys like me.

When it comes to guns, I am pretty sure I’m the guy she had in mind. On more than a few occasions, I’ll get fired up about a firearm (no pun intended), and then several of my friends will buy the same thing. It’s happened with Mosin-Nagants, 1911 .45 autos, Ruger No. 1 rifles, and most recently, big-bore Marlins. Caliber .45 70 Model 1895s, to be precise. Several of my friends now own these rifles and they are a hoot. One of these days we’ll have one of our informal West End Gun Club matches and restrict it to .45 70 rifles only. That should be fun.

I was in northern California last week and that’s always a good opportunity to visit with my good buddy Paul and send a little lead downrange. Well, maybe not a little. You see, Paul recently purchased a .45 70 Marlin 1895, and these rifles send lead downrange at the rate of 400 grains a shot. There are 7,000 grains in a pound. Do the math…that’s a big-ass bullet. Hell, they used to use these things for shooting buffalo.

The Marlins are great rifles, and you can pick up a 45 70 Model 1895 for around $600 if you shop around for a bit. Marlin was acquired by Remington a few years ago, and their quality took a hit during the transition as they moved production from the old Marlin factory in Connecticut to the Remington plant in New York. Judging by the recent rifles I’ve examined (including Paul’s), the quality issues are all in the rear-view mirror now. The new Marlins sure shoot well, too.

Paul added a Williams aperture rear sight to his 1895, and this was the first time he shot it. I had spotting duties. The first round went low left about 10 inches, and then Paul walked succeeding rounds up and to the right by adjusting the rear sight as I called the shots to him. It didn’t take too many shots to zero the rifle, and from that point on, it was simply a question of evaluating which of several different handloads grouped best. Paul had prepared test rounds using Unique and IMR 4227 propellant, all using the Missouri 400 grain cast lead bullet. The winner was 13.0 grains of Unique behind the mighty Missouri slug. At 50 yards, this load grouped well.

We were at a Santa Clara County public range and it was a rainy day, but we managed to have fun on both the rifle and handgun ranges. We shot the .45 70 and then my personal favorite handgun, the 1911 .45 Auto. Yep, Paul had his 1911 out, and we had fun with it, too.

Paul let me try the Marlin. He tried to capture the muzzle blast, but timing the camera to the shot is tough.

Other folks on the range are always intrigued by the .45 70 cartridge. Compared to the most common rounds seen on rifle ranges these days, they’re huge. The perception is that the recoil must be horrendous. It can be if you load near the upper end of the propellant charge spectrum, but at the lower powder charge ranges, these guns are a lot of fun. That’s a topic for another blog, one that will appear here soon. Stay tuned!

Want to read our other ExhaustNotes Tales of the Gun stories? Just click here!

Long Beach Vintage Motos

I grabbed just a few vintage motorcycle shots at the Long Beach show last weekend. There were quite a few vintage bikes there, but there were also many other interesting things to photograph. Here are just a few.

Like I said, there were many more vintage machines at Long Beach this year, and what I included here is just a small sample. It was a grand show.

Okay, one more…of little old me reflected in one of the Royal Enfield fuel tanks.

Double Vision

Water Canyon Road, west of Socorro, New Mexico is paved all the way to the Water Canyon Campground. The Campground is beautiful, wooded and self-serve: You put your fees into a pipe and pitch your tent. There are clean pit toilets and yodeling coyotes along with bear-proof trash cans. I’d like to hang out here but we are heading to The Magdalena Ridge Observatory.

Water Canyon Road, west of Socorro, New Mexico is paved all the way to the Water Canyon Campground. The Campground is beautiful, wooded and self-serve: You put your fees into a pipe and pitch your tent. There are clean pit toilets and yodeling coyotes along with bear-proof trash cans. I’d like to hang out here but we are heading to The Magdalena Ridge Observatory.

Water Canyon Road continues on for another 13 miles of unpaved road. It’s not a terrible road: a regular car could do it if you didn’t mind cutting a few low-profile tires and maybe bashing the undercarriage. The sign says 4-wheel drive only and I guess that’s the best way to go. The drop-offs are wonderful and steep, the views towards the valley are eye-twisting.

Even if the scenery was terrible Water Canyon would be worth the drive because the road ends on top of Mt. Baldy and one of the newest, gigantic telescopes under construction. When completed, the Magdalena Ridge Interferometer will have ten 1.4-meter optical telescopes interconnected to provide the resolution equal to a 340-meter diameter mirror (at max zoom). That’s over one thousand feet and that’s a big mirror, my brothers; for comparison the Hubble Space Telescope is 2.4-meters or 8 feet. Nine of the 1.4-meter telescopes will be movable allowing the mirror to reduce in equivalent size to 7.8 meters for those cool, wide-angle shots. One mirror remains in the center.

It’ll be a clunky system. There are no tracks to smoothly zoom in and out. A crane will lift the telescopes and relocate them on pads so changing focal length will be a several day operation. Clunky or not, it will be a huge telescope limited only by the Earth’s atmosphere and the small amount of light gathering surface relative to the size of the array.

The ten telescopes will send an image through pipes to the control room. A vacuum will be maintained inside the pipes to reduce distortion and all ten feeds will be reassembled inside the control room to produce what should be some spectacular space photography. Think of the whole operation as a Very Large Array except in the visible wavelengths.

This pipe will be joined by 9 more. Inside each of the ten pipes in this section will be a shuttle to adjust the information beam’s timing. This adjustment is needed because the light source will always strike the individual telescopes at slightly different times due to their distance from the source. From here they shoot into the control room and the open air.

At the moment the Interferometer has only one mirror. Any high-rollers reading ExNotes who can contribute 11 million dollars to finish the other 9 telescopes would find little resistance to naming the whole damn place after their recently deceased cat. Or themselves.

Like Popeil’s Ginsu knife deal, that’s not all! A short distance away on the same mountaintop is the Magdalena Ridge Observatory, a 2.4-meter, fast reacting telescope presently engaged by the government for tracking Earth orbiting objects. I imagine the idea is to identify and locate the other guy’s space stuff for future elimination in times of war. They can also track missile launches and aircraft as the gimbal is ten times faster than a garden variety telescope.

The mirror at the MRO is an ex-Hubble part of which there were three built; one is inside Hubble floating around space, the other is at The National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

The mirror at the MRO is an ex-Hubble part of which there were three built; one is inside Hubble floating around space, the other is at The National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

Tours of the Magdalena Ridge facility are infrequent, but don’t let that stop you from taking the ride up to the top. Check online for times and dates.

The Long Beach Customs

We sure enjoyed our time at the Long Beach International Motorcycle Show, and I had a great time photographing the custom bikes. The concept behind the motorcycle shows is that the manufacturers get to display their bikes, vendors get to display (and sell) their products, and in the midst of all, the aisles are peppered with custom bikes. The audience gets to vote and someone gets a trophy, I guess. I just like seeing the latest trends and the craftsmanship that goes into these customs. Take a look.

I think one of the great aspects of these shows is that the custom motorcycles suggest ideas for future customs. They’re fun to see and fun to photograph. All of these photos were shot with available light (no flash) with my Nikon D810 at ISO 1000 and the 24-120 Nikon lens. There were many more customs than just the ones I’m showing here, but this blog is getting long enough already, and I have other things I want to share with you from the Long Beach International Motorcycle Show. Stay tuned!

Good Buddies in Long Beach…

One of the best parts of the Long Beach International Motorcycle Show is always running into good friends. Here are a few good buddies we saw last weekend at the show.

I always enjoy seeing friends at the Long Beach Moto Show. It’s the best part of the show for me.

Why a 250?

This is a blog I wrote for CSC Motorcycles a little more than 4 years ago (time sure flies when you’re having fun). The topic was as timely then as it is today. I like big bikes, but I like small bikes more, and I’m convinced that a small bike makes way more sense than a big bike for real world adventure touring. I thought I would post the blog again, as we are having way too much fun with CSC, BMW, Janus, and other companies who have seen the light. Here’s the blog from back in September 2014…

A 250cc bike seems too small to many riders. Is it?

The motorcycle craze in the US really started in the mid-1960s. I know motorcycling goes back way before that, but motorcycling was essentially a fringe endeavor until Honda came on the scene. We met the nicest people on Hondas, if you remember, and that ad tagline was a winner (so is “Don’t Miss The Boat,” by the way). (Note: “Don’t Miss The Boat” was CSC’s tagline for the US RX3 introduction, and those who didn’t miss the boat participated in one of the best deals in the history of motorcycling.)

Honda’s sales model was a good one. They pulled us in with small bikes and then convinced us we needed larger and larger bikes. Many of us started with a Honda Cub (the 50cc step-through), we progressed to the Super 90 (that was my jump in), then the 160cc baby Super Hawk, then the 305cc Super Hawk, and at that point in about 1967 that was it for Honda. They didn’t have anything bigger (yet). After the 305cc Super Hawk, the next step for most folks was either a Harley or a Triumph.

You know, back in those days, a 650cc motorcycle was a BIG motorcycle. And it was.

But Honda kept on trucking…they offered a 450 that sort of flopped, and then in 1969 they delivered the CB-750. That bike was so far out in front of everyone else it killed the British motorcycle industry and (with a lot of self-inflicted wounds) it almost killed Harley.

The Japanese manufacturers piled on. Kawasaki one-upped Honda with a 900. (Another note…it’s one of those early Kawi 900s that Gobi Gresh is restoring in the Zed’s Not Dead series.) Honda came back with a 1000cc Gold Wing (which subsequently grew to 1100cc, then 1500cc, and is now an 1800cc). Triumph has a 2300cc road bike. Harley gave up on cubic centimeters and now describes their bikes with cubic inches. And on and on it went. It seems to keep on going. The bikes keep on getting bigger. And bigger. And bigger. And taller. And heavier. And bigger. In a society where everything was being supersized (burgers, bikes, and unfortunately, our beltlines), bigger bikes have ruled the roost for a long time. Too long, in my opinion.

Weirdly, today many folks think of a 750 as a small bike. It’s a world gone nuts. But I digress…

I’ve done a lot of riding. Real riding. My bikes get used. A lot. I don’t much care for the idea of bikes as driveway jewelry, and on a lot of my rides in the US, Mexico, and Canada, I kind of realized that this “bigger is better” mentality is just flat wrong. It worked as a motorcycle marketing strategy for a while, but when you’re wrestling with a 700-lb bike in the soft stuff, you realize it doesn’t make any sense.

I’ve had some killer big bikes. A Triumph Daytona 1200. A Harley Softail. A TL1000S Suzuki. A Triumph Speed Triple (often called the Speed Cripple, which in my case sort of turned out to be true). All the while I was riding these monsters, I’d see guys on Gold Wings and other 2-liter leviathans and wonder…what are these folks thinking?

I’d always wanted a KLR-650 for a lot of reasons. The biggest reasons were the bikes were inexpensive back then and they were lighter than the armored vehicles I had been riding. I liked the idea of a bike I could travel on, take off road, and lift by myself if I dropped it. To make a long story short, I bought the KLR and I liked it. I still have it. But it’s tall, and it’s heavy (well over 500 lbs fully fueled). But it was a better deal than the bigger bikes for real world riding. Nobody buys a KLR to be a poser, nobody chromes out a KLR, and nobody buys leather fringe for a KLR, but if that’s what you want in a motorcycle, hey, more power to you.

More background…if you’ve been on this blog for more than 10 minutes you know I love riding in Baja. I talk about it all the time. My friends tell me I should be on the Baja Tourism Board. Whatever. It is some of the best riding in the world. I’ll get down there the first week I take delivery on my CSC Cyclone, and if you want to ride with me, you’re more than welcome. (Note: And I did. We did a lot of CSC Baja tours, and CSC introduced a lot of folks to riding and to Baja. That one innocent little sentence became a cornerstone of CSC’s marketing strategy.)

I was talking up Baja one day at the First Church of Bob (the BMW dealership where me and some of my buddies hang out on Saturday mornings). There I was, talking about the road to San Felipe through Tecate, when my good buddy Bob said “let’s do it.” Baja it was…the other guys were on their Harleys and uber-Beemers, and I was on my “small bore” KLR. The next weekend we pointed the bars south, wicked it up, and rode to San Felipe.

That was a fun trip. I took a lot of ribbing about the KLR, but the funny thing was I had no problem keeping up with the monster motos. In fact, most of the time, I was in the lead. And Bob? Well, he just kept studying the KLR. On Saturday night, he opened up a bit. Bob is the real deal…he rode the length of Baja before there was a road. That’s why he was enjoying this trip so much, and it’s why he was so interested in my smaller bike. In fact, he announced his intent to buy a smaller bike, which surprised everybody at the table.

Bob told us about a months-long moto trip he made to Alaska decades ago, and his dream about someday riding to Tierra del Fuego. That’s the southernmost tip of South America. He’d been to the Arctic Circle, and he wanted to be able to say that he’d been all the way south, too.

I thought all of this was incredibly interesting. Bob is usually a very quiet guy. He’s the best rider I’ve ever known, and I’ve watched him smoke Ricky Racers on the Angeles Crest Highway with what appeared to be no effort whatsoever. Sometimes he’d do it on a BMW trade-in police bike standing straight up on the pegs passing youngsters on Gixxers and Ducksters. Those kids had bikes with twice the horsepower and two-thirds the weight of Bob’s bike, and he could still out ride them. Awesome stuff. Anyway, Bob usually doesn’t talk much, but during dinner that night on the Sea of Cortez he was opening up about some of his epic rides. It was good stuff.

Finally, I asked: Bob, what bike would you use for a trip through South America?

Bob’s answer was immediate: A 250.

That surprised me, but only for an instant. I asked why and he told me, but I kind of knew the answer already. Bob’s take on why a 250: It’s light, it’s fast enough, it’s small enough that you can pick it up when it falls, you can change tires on it easily, you can take it off road, you can get across streams, and it gets good gas mileage.

Bob’s answer about a 250 really stuck in my mind. This guy knows more about motorcycles than I ever will, he is the best rider I’ve ever known, and he didn’t blink an eye before immediately answering that a 250 is the best bike for serious world travel.

It all made a lot of sense to me. I had ridden my liter-sized Triumph Tiger in Mexico, but when I took it off road the thing was terrifying. The bike weighed north of 600 lbs, it was way too tall, and I had nearly dropped it several times in soft sand. It was not fun. I remembered another ride with my friend Dave when he dropped his FJR in an ocean-sized puddle. It took three of us to get the thing upright, and we dropped it a couple of more times in our attempt to do so. John and I had taken my Harley and his Virago on some fun trips, but folks, those bikes made no sense at all for the kind of riding we did.

You might be wondering…what about the other so-called adventure bikes, like the BMW GS series, the Yamaha Tenere, or the Triumph Tiger? Good bikes, to be sure, but truth be told, they’re really street bikes dressed up like dirt bikes. Big street bikes dressed up like dirt bikes. Two things to keep in mind…seat height and weight. I can’t touch the ground when I get on a BMW GS, and as you’ve heard me say before, my days of spending $20K or $30K on a motorcycle are over. Nice bikes and super nice for freeway travel, but for around town or off road or long trips into unknown territory, these bikes are just too big, too heavy, and too tall.

There’s one other benefit to a small bike. Remember that stuff above about Honda’s 1960s marketing strategy? You know, starting on smaller bikes? Call me crazy, but when I get on bikes this size, I feel like a kid again. It’s fun.

I’ve thought about this long and hard. For my kind of riding, a 250 makes perfect sense. My invitation to you is to do the same kind of thinking.

So there you have it. That was the blog that helped to get the RX3 rolling, and CSC sold a lot of RX3 motorcycles. Back in the day, CSC was way out in front of everybody on the Internet publicizing the Zongshen 250cc ADV bikes, and other countries took notice. Colombia ordered several thousand RX3s based on what they CSC doing, other countries followed, and things just kept getting better and better. The central premise is still there, and it still makes sense. A 250 may well be the perfect motorcycle.

Never miss an ExNotes blog…subscribe here for free!

Baja Bound with Janus Motorcycles!

It’s a go, and it’s going to be a grand adventure. In just a few days we’re headed to Baja with the good guys from Janus Motorcycles!

I’m excited about this trip. It’s four days and roughly a thousand miles, I’ll be riding with Devin and Jordan from Janus Motorcycles, and we’ll all be on 250cc Janus classic bikes. We’re hitting the best of southern California’s mountains and forests, Tecate, San Felipe, the Sea of Cortez, the Rumarosa Grade, Ensenada, the northern Baja wine country, and more. Fish tacos. Lobster burritos. Chilequiles. Birreria. Tequila (after the bikes are put away for the night, of course). It’s going to be grand, and you’ll be able to follow the adventure each day right here on the ExhaustNotes blog. We’ll be riding some of the most beautiful roads in one of the most beautiful parts on the planet, and you can bet we’ll be covered by our good buddies from BajaBound Insurance.

This will be my first ride on a Janus Motorcycle, and I’m very much looking forward to the experience. A classic lightweight British-styled motorcycle manufactured right here in the United States, powered by the iconic and bulletproof CG engine, on a run through northern Baja…this is going to be awesome!

Want to read the rest of the story? Please visit our Baja page for an index to all of the Janus Baja blog posts!

The BMW G 310 GS

I’ve become a small bike guy. I rode big miles on 250cc motorcycles in Asia, South America, Mexico, and the US, and I’m naturally interested in any motorcycle of that approximate displacement. It’s no secret I was a consultant to CSC Motorcycles for about a decade and I was involved in the effort to bring the RX3 and the TT250 to America. There. Having said that, let’s move into the topic of this blog, and that’s BMW’s contenders in this class, their 310cc entries. They have two. One is a street-oriented bike (the R 310), and the other is more styled along the lines of the BMW’s bigger GS bikes (the G 310 GS). I examined both motorcycles and I rode the GS version. My good buddies at Brown BMW provided the bikes and answered all of my questions.

My intent here is not to do a direct comparison of the Baby Beemer to the CSC bikes, although the comparisons are inevitable. I’m not going to dwell on them, though. If you want to learn more about the CSC bikes, my advice is to go to the ExhaustNotes RX3-to-RX4 comparos, or go directly to the CSC website.

After CSC introduced the RX3 in 2015, the motorcycle world took notice. Three manufacturers subsequently entered the market with small-displacement ADV bikes. One was BMW, another was Royal Enfield, and a third was Kawasaki. The Royal Enfield is a 400cc single; I haven’t ridden it (although I understand Royal Enfield dealers give test rides; one of these days I’ll get around to riding one). The Kawasaki is a 300cc twin; I haven’t ridden it (Kawasaki dealers typically do not allow test rides). Gresh rode the Kawasaki when he was invited to the little Kawi’s intro and he did a video on it. BMW allows test rides (as does CSC), so I was able to ride the BMW. I know that Honda, Yamaha, and Suzuki all have 250 and 300cc bikes, too, but those are street-oriented bikes and they are not equipped for adventure touring. I don’t consider them competitors in this class. Basically, if you want a small ADV bike, it’s CSC, BMW, Kawasaki, or Royal Enfield.

Let’s get the heavy lifting out of the way first and tackle the gorillas in the room: Price and country of origin. Here’s the bottom line…the street-oriented BMW, the R 310, is $4950 for a 2018 model. That includes freight and setup; it does not include tax and documentation fees. The G 310 GS (the adventure version and the primary focus of this blog) is another thousand bucks at $5940 (again, that includes freight and setup, but does not include tax and doc fees). That’s with both bikes bare (no accessories).

Before continuing with the pricing discussion, let’s hit that country-of-origin thing. These bikes are built for BMW in India. Some folks might have an issue with that. I’m not one of them. I examined the bikes (the R and the GS models) and their fit and finish is top notch. I guess BMW feels that way, too, and they back it up: The 310cc bikes have the same 3-year, 36000-mile warranty as do the bigger BMW motorcycles. That’s better than CSC, Yamaha, Honda, Royal Enfield, and Kawasaki.

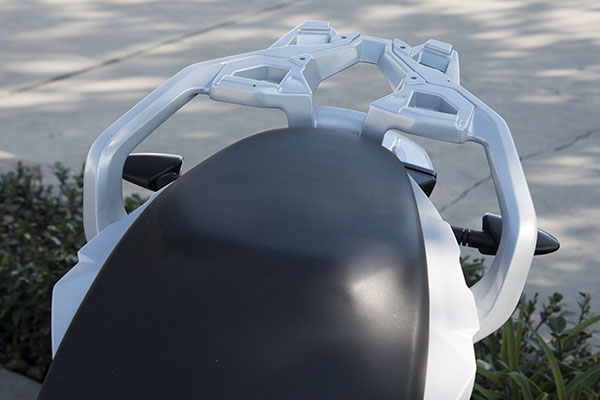

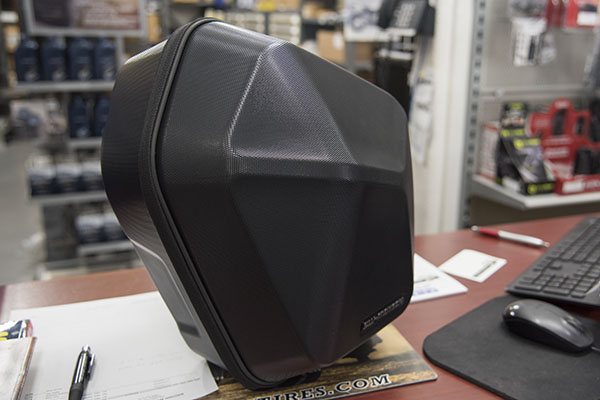

Okay, back to pricing and some of the details to get the bikes ADV-ready. If you want to add a tailbox to the R model, for the rack (which the R model does not include as standard equipment), it’s another $218, and for the tailbox, it’s $181. The Brown BMW parts guy told me that with the necessary hardware and taxes, the tailbox and rack come out to $457. The GS model comes with the rear rack as standard equipment, but to add the tailbox it’s that $181 figure. If you want to add panniers to the GS model, with the mounts and adaptors it’s another $709. If you want your baby Beemer GS to include a tailbox and panniers, you’re looking at adding roughly $900 to the bike. That brings the price of the GS model to $5940 plus $900, or $6840 (not including tax and doc fees). And that’s for a 2018 model. Prices are going up in 2019. I’ll get to that in a bit.

All of these numbers are for the 2018 model bikes. If you want to get a 2019 model, both bikes are going up another $750. That would put a panniers-and-topcase equipped 2019 model at just under $7600, not counting taxes and documentation fees. Refreshingly, BMW’s practice is to include freight and setup in the bike’s pricing and not leave that up to the dealers. The Big 4 let the dealers decide on their freight and setup fees, and, well, don’t get me started on that topic. Let’s just say that the way BMW does it is light years ahead of the Big 4 dealers in terms of transparency, honesty, and consistency.

Let’s hit a few of the tech features on the GS before describing the ride. The GS model has cast wheels (17-inch in the rear, and 19-inch in the front). There is no wire wheel option, which is surprising given the bike’s GS heritage. There’s an argument to be made for wire wheels instead of cast wheels for serious adventure touring. There’s also an argument to be made for cast wheels and tubeless tires. It’s a “Here’s your shovel, take your pick” discussion. BMW chose cast wheels. It wouldn’t be a deal breaker for me. I can live with either approach.

Both 310 models are chain drive, and both bikes use a single-cylinder, liquid-cooled, fuel-injected engine. The engine is sort of a vertical single (I say “sort of” because the cylinder is inclined 10 degrees to the rear). Body work obscures most of the cylinder, so it doesn’t look as unusual as it sounds. Interestingly, the intake and exhaust are reversed from what we are used to seeing. The fuel injector is in front of the engine and the exhaust pipe exits to the rear. (To go tangential for a moment, Mustang used this approach in their earlier models in the 1950s. Those bikes also had 300cc engines; the Mustang engines were originally designed to power cement mixers. Really. I can’t make this stuff up. You can read more about the early Mustangs here.) It’s interesting to see the reversed intake/exhaust approach on a modern motorcycle. You could make the argument that tilting the cylinder to the rear adds to mass centralization (cue in the Erik Buell theme song), but I don’t know if that was the logic that drove this design.

The little GS instrumentation is all digital and indicator lights. It’s a good display. I didn’t like the tachometer approach. It has a horizontal linear readout along the bottom of the dash, and I had a hard time seeing it. Having said that, I will offer a radical thought: I think a tachometer is superfluous on a motorcycle. It’s interesting to see how fast the engine is revving, but I never rely on the tach for shifting or anything else. If you need a tach to tell you when to shift, you have no mechanical empathy (a topic to be covered in a later ExNotes blog). But that’s just me, and like I said, I know its heresy in the motorcycle world. I didn’t check speedo accuracy with a GPS because the GS I rode was brand new and it did not have a cellphone mount.

I asked the Brown BMW sales manager (Tom Reece, a genuine good guy) about speedometer accuracy and he told me the speedo was optimistic, which seems to me to be the case on every motorcycle I’ve ever ridden. Curiously, though, the last four cars I’ve owned all had speedometers that were within 1 mph of the GPS reading. It seems to me the motorcycle industry would do well to steal a speedometer engineer away from one of the auto companies.

Both 310cc BMWs had a single disk in the front. It felt good to me. The bikes have ABS as standard equipment, and it’s switchable (you can turn it on or off from a left-handlebar switch). The other controls on the handlebar switchgear are conventional, including the turn signals (there’s none of the turn signal tomfoolery that you find on the larger BMW motorcycles). I did not see any outlets on the bike I rode for USB or 12V charging. Maybe they’re there and I missed them.

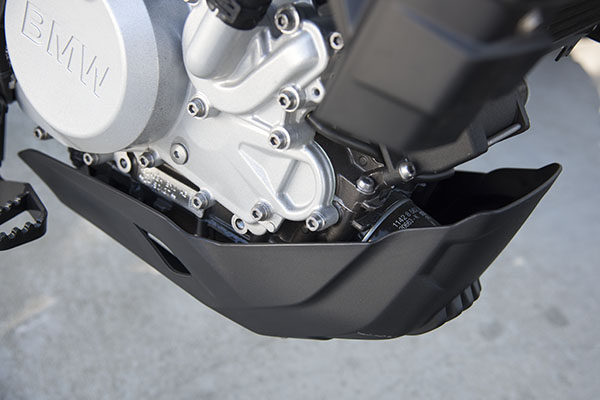

One potential negative is the oil filter location on both bikes. Both use a spin-on oil filter that is mounted low and on the front of the engine. Stated differently, the filter is directly in line with anything the front tire kicks up. I think that could be a liability off road, and perhaps even on road. My Triumph Tiger had a spin-on filter that was mounted underneath the engine (and mostly inside the engine, as the crankcase was recessed to protect the filter). I somehow managed to kick up a screwdriver with my front tire several years ago on the San Bernardino Freeway, the screwdriver penetrated the oil filter, and all of a sudden the rear end of my Triumph was sashaying around like an exotic dancer in a room full of big tippers (oil had sprayed all over the rear tire). The BMWs both have a skid plate of sorts, but it’s plastic and it looks kind of flimsy to me. I don’t think it’s the answer to crashing around in a field of boulders.

On to the ride: I didn’t put a lot of miles on the GS and it was all in town. The bike felt peppy, and it might beat the RX3 in a drag race (especially since the one I rode wasn’t carrying the added weight of the RX3’s engine guards, steel skidplate, topcase and bags, and windshield). On that windshield thing…neither of the BMWs has a windshield, although they both have black wind deflectors. Again, I didn’t rack up any freeway miles, but around town, wind was not an issue.

Both of the little BMWs had constant diameter (i.e., non-tapered) handlebars. I always thought that tapered handlebars were a little bit of a marketing gimmick, but I could feel a difference in vibration between the BMW I rode and other bikes with tapered handlebars. I am assuming the BMW engine is counterbalanced (and my research tells me the bike has a counterbalancer), but the vibration still gets through. Looking at my photos, I don’t see where the counterbalancer would be located (the conventi0nal location in the crankcase forward area appears to be the spot that mounts the starter motor). The vibration at higher rpm wasn’t offensive, but it was noticeable. At the end of a 300-mile day, it would probably be more noticeable.

The G 310 GS ride was comfortable. In fact, it felt good. The suspension is adjustable for preload only in the rear. There’s no preload adjustment up front, and no damping adjustment in the front or the rear. The bike comes with a tool for the rear preload adjustment. The GS has 7 inches of suspension travel at both ends. The GS’s seat height was a reasonable 33 inches, and I had no problem getting on or off the bike (nor did I have any issues when stopping).

To cut to the chase, the G 310 GS rode well and it felt secure. If I wanted a sensibly-sized (read: small) bike and if I was a BMW kind of guy, I’d have no reservations about owning this bike. And if I was going to buy a BMW, there’s no doubt in my mind it would be from Brown’s. I know and have ridden with both Bob Brown (the founder) and Dave Brown (the general manager), they are both great guys, and going any place else to buy a BMW just wouldn’t make sense.

After my ride, I had a ton of questions for the guys at Brown BMW, and I’ve included their answers in the above discussion. There were one or two other things I wanted to mention. I asked if there had been any reliability or service issues with the bike. Tom told me there had been a recall for a sidestand issue. Brown’s didn’t have any sidestand failures, but the Service Department made the sidestand mods to satisfy the recall. It happens. I’ve seen recalls for some pretty mundane issues on other makes, and it sounds like this was one of them.

The other question I asked was about the shop manual. Tom looked at me quizzically and then he told me they hadn’t sold a service manual for any of their motorcycles in years. I said at the outset of this blog that I didn’t want it to be a CSC-to-BMW comparo, but I guess this is one of the fundamental differences between the two organizations I need to mention. CSC gives its customers a free shop manual, they have online tutorials, and they encourage their customers to do their own maintenance. That’s an approach mandated by CSC’s path to market (they don’t sell through dealers). BMW, which only sells through dealers, makes it almost a requirement that customers rely on dealer service departments. It seems to be an approach that works for BMW, and the guys I ride with who have BMWs all say Brown’s service is top drawer.

I liked the 310cc BMW, and I’d have no problem getting on one and riding across China, or Mexico, or the United States, or India (now there’s a cool idea). I’d be a bit concerned about the lack of a shop manual, but that’s just me. If you’re a died-in-the-wool BMW type and you don’t want to do your own maintenance, I can see where this bike makes sense. I think that’s what BMW is relying on. Tom told me they sell the 310cc bikes to new riders and to guys who already own larger BMWs. Tom said younger guys stop by in their 3-series BMW automobiles, they see a $6K BMW motorcycle, and they think “hey, that’s not too bad.”

I think BMW views its 310cc bikes as an opportunity to introduce new riders to motorcycling (always a good thing) and ultimately, to upsell them to the larger BMW bikes. There’s nothing wrong with that, but I think BMW might be missing the boat. When I rode the G 310 GS, here’s the question I was thinking about: Would I travel big time on this bike? Say a trip down to Cabo San Lucas and back? The answer is yes. Where I think BMW might be remiss is they are not positioning the 310 as a serious long-distance adventure machine. I examined BMW’s website and I did a Google search on GS310 adventure rides, and not a lot shows up. The BMW website talks about the bike being good for around town and trail rides. I think it’s good for a lot more than that. Maybe the Bavarians are worried about cannibalizing sales of their larger bikes, but if I was BMW I’d be pushing the hell out of the 310 for real world adventure touring. The bike is the right size and I think it has the chops. Along those same lines, if I were BMW I’d be organizing 310 adventure rides to Baja, Alaska, and some of our great destinations here in the US. It’s an approach that sells motorcycles and pulls people into riding. I can tell you that from personal experience.