By Joe Berk

For me a motorcycle’s appearance, appeal, and personality are defined by its motor. I’m not a chopper guy, but I like the look of a chopper because the engine absolutely dominates the bike. I suppose to some people fully faired motorcycles are beautiful, but I’m not in that camp. The only somewhat fully faired bike I ever had was my 1995 Triumph Daytona 1200, but you could still see a lot of the engine on that machine. I once wrote a Destinations piece for Motorcycle Classics on the Solvang Vintage Motorcycle Museum and while doing so I called Virgil Elings, the wealthy entrepreneur who owned it. I asked Elings what drove his interest in collecting motorcycles. His answer? The motors. He spoke about the mechanical beauty of a motorcycle’s engine, and that prompted me to ask for his thoughts on fully faired bikes. “I suppose they’re beautiful to some,” he said, “but when you take the fairings off, they look like washing machines.” I had a good laugh. His observation was spot on.

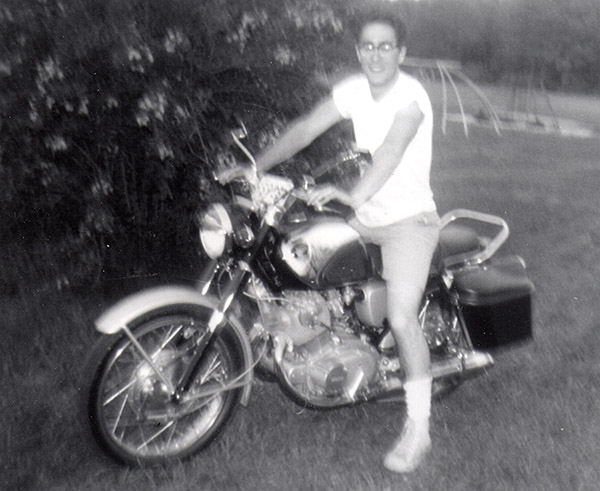

My earliest memory of drooling over a motorcycle occurred sometime in the 1950s when I was a little kid. My Mom was shopping with me somewhere in one of those unenclosed malls on Route 18 in New Jersey, and in those days, it was no big deal to let your kid wander off and explore while you shopped. I think it was some kind of a general store (I have no idea what Mom was looking for), and I wandered outside on the store’s sidewalk. There was a blue Harley Panhead parked out front, and it was the first time I ever had a close look at a motorcycle. It was beautiful, and the motor was especially beautiful. It had those early panhead corrugated exhaust headers, fins, cables, chrome, and more. I’ve always been fascinated by all things mechanical, and you just couldn’t find anything more mechanical than a Big Twin engine.

There have been a few Sportsters that do it for me, too, like Harley’s Cafe Racer from the late 1970s. That was a fine-looking machine dominated by its engine. I liked the Harley XR1000, too.

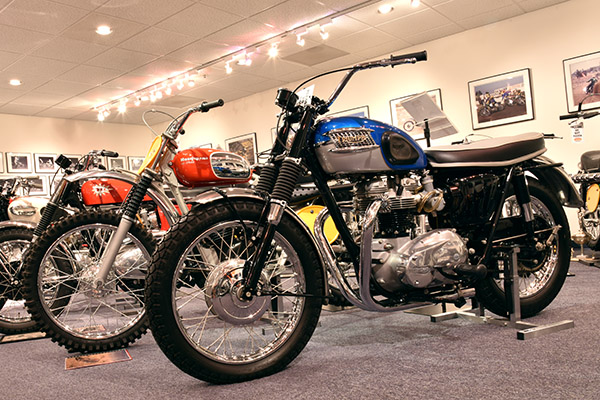

I’ve previously mentioned my 7th grade fascination with Walt Skok’s Triumph Tiger. It had the same mesmerizing motorrific effect as the big twin Panhead described above. I could stare at that 500cc Triumph engine for hours (and I did). The 650 Triumphs were somehow even more appealing. The mid-’60s Triumphs are the most beautiful motorcycles in the world (you might think otherwise and that’s okay…you have my permission to be wrong).

BSA did a nice job with their engine design, too. Their 650 twins in the ’60s looked a lot like Triumph’s, and that’s a good thing. I see these bikes at the Hansen Dam Norton Owners Club meets. They photograph incredibly well, as do nearly all vintage British twins.

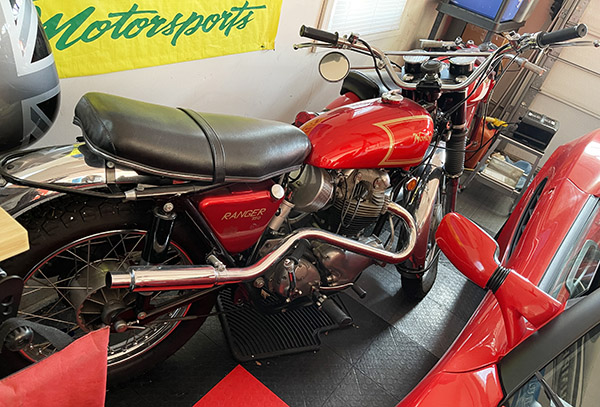

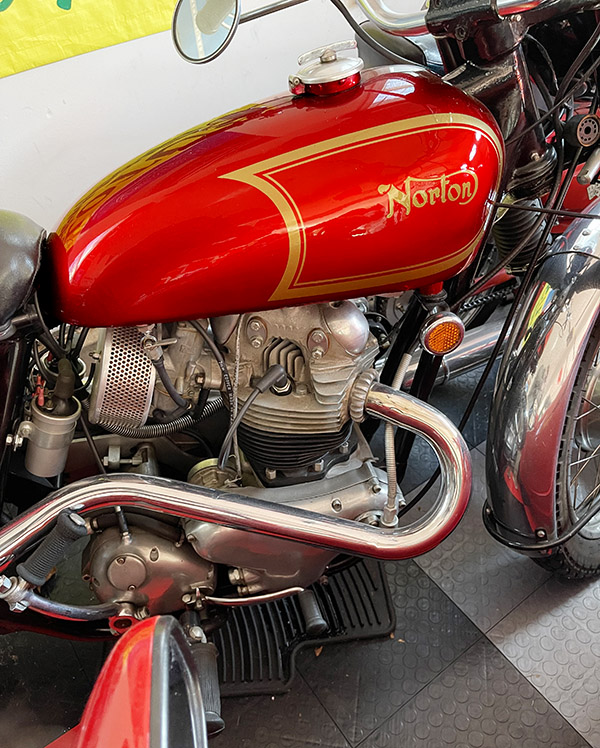

When we visited good buddy Andrew in New Jersey recently, he had several interesting machines, but the one that riveted my attention was his Norton P11. It’s 750cc air cooled engine is, well, just wonderful. If I owned that bike I’d probably stare at it for a few minutes every day. You know, just to keep my batteries charged.

You know, it’s kind of funny…back in the 1960s I thought Royal Enfield’s 750cc big twins were clunky looking. Then the new Royal Enfield 650 INT (aka the Interceptor to those of us unintimidated by liability issues) emerged. Its appearance was loosely based on those clunky old English Enfields, but the new twin’s Indian designers somehow made the engine look way better. It’s not clunky at all, and the boys from Mumbai made their interpretive copy of an old English twin look more British than the original. The new Enfield Interceptor is a unit construction engine, but the way the polished aluminum covers are designed it looks like a pre-unit construction engine. The guys from the subcontinent hit a home run with that one. I ought to know; after Gresh and I road tested one of these for Enfield North America on a Baja ride, I bought one.

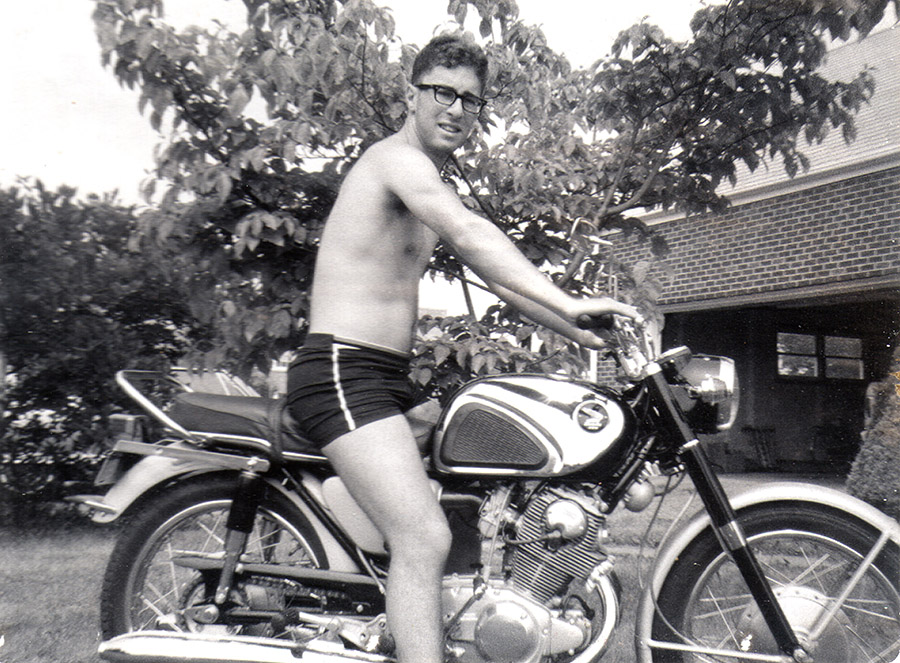

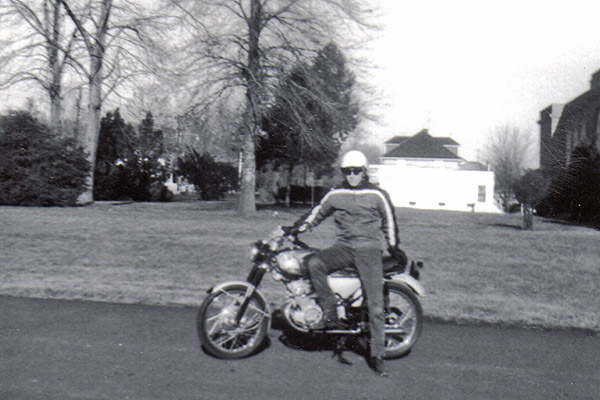

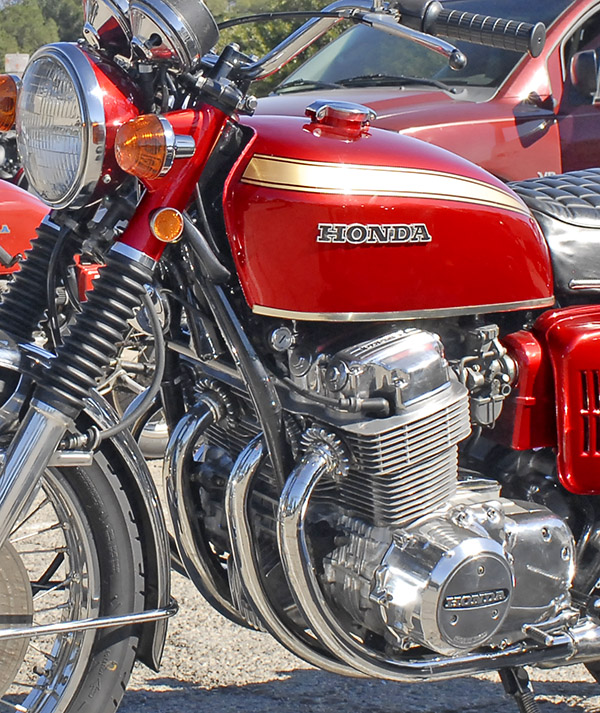

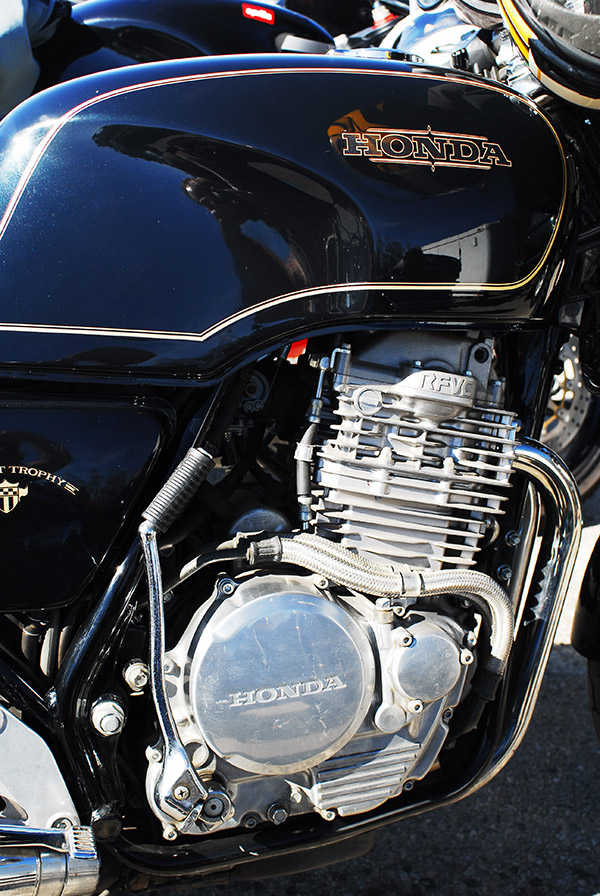

Another motorcycle that let you see its glorious air-cooled magnificence was the CB750 Honda. It was awesome in every regard and presented well from any angle, including the rear (which is how most other riders saw it on the road). The engine was beyond impressive, and when it was introduced, I knew I would have one someday (I made that dream come true in 1971). I still can’t see one without taking my iPhone out to grab a photo.

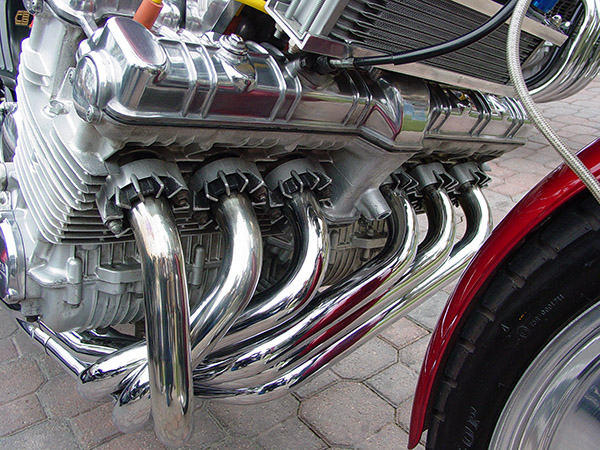

After Honda stunned the world with their 750 Four, the copycats piled on. Not to be outdone, Honda stunned the world again when they introduced their six-cylinder CBX. I had an ’82. It was awesome. It wasn’t the fastest motorcycle I ever owned, but it was one of the coolest (and what drove that coolness was its air-cooled straight six engine).

Like they did with the 750 Four, Kawasaki copied the Honda six cylinder, but the Kawasaki engine was water-cooled and from an aesthetics perspective, it was just a big lump. The Honda was a finely-finned work of art. I never wanted a Kawasaki Six; I still regret selling my Honda CBX. The CBX was an extremely good-looking motorcycle. It was all engine. What completed the look for me were the six chrome exhaust headers emerging from in front. I put 20,000 miles on mine and sold it for what it cost me, and now someone else is enjoying it. The CBX was stunning motorcycle, but you don’t need six cylinders to make a motorcycle beautiful. Some companies managed to do it with just two, and some with only one. Consider the engines mentioned at the start of this piece (Harley, Triumph, BSA, and Norton).

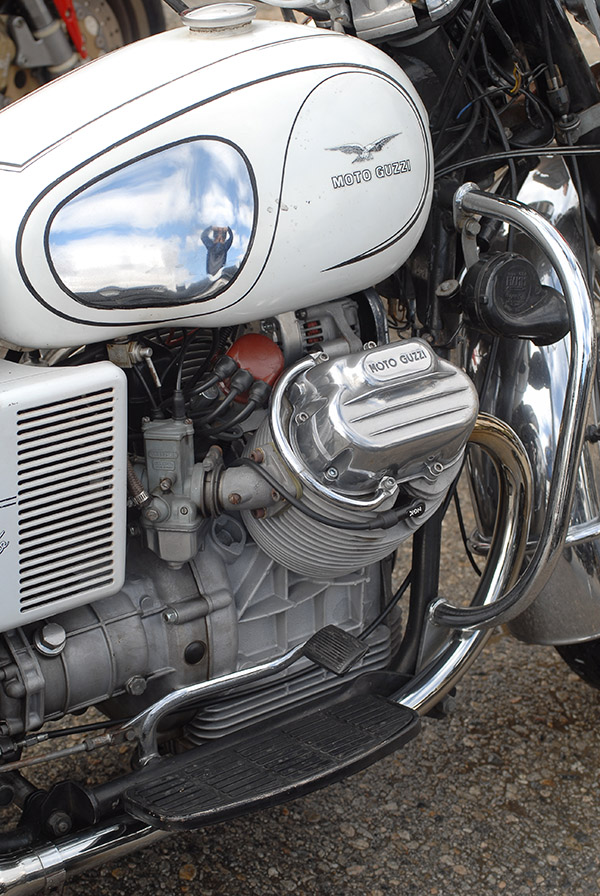

Moto Guzzi’s air-cooled V-twins are in a class by themselves. I love the look and the sound of an air-cooled Guzzi V-twin. It’s classy. I like it.

Some motorcycle manufacturers made machines that were mesmerizing with but a single cylinder, so much so that they inspired modern reproductions, and then copies of those reproductions. Consider Honda’s GB500, and more than a few motorcycles from China and even here in the US that use variants of the GB500 engine.

The GB500 is a water cooled bike, but Sochoiro’s boys did it right. The engine is perfect. Like I said above, variants of that engine are still made in China and Italy; one of those engines powers the new Janus 450 Halcyon.

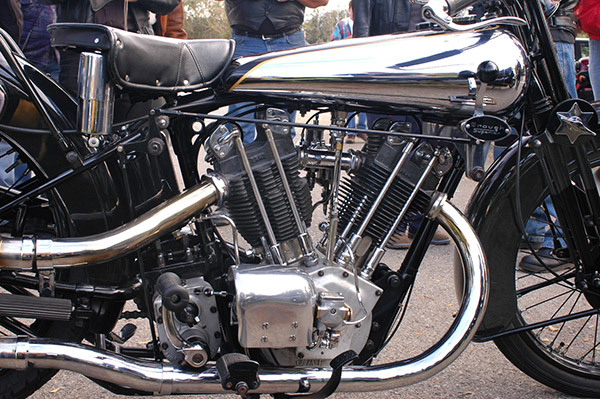

No discussion of mechanical magnificence would be complete without mentioning two of the most beautiful motorcycles ever made: The Brough Superior SS100 and the mighty Vincent. The Brits’ ability to design a visually arresting, aesthetically pleasing motorcycle engine must be a genetic trait. Take a look at these machines.

Two additional bits of moto exotica are the early inline and air-cooled four-cylinder Henderson, and the Thor, one of the very first V-twin engine designs. Both of these boast American ancestry.

The Henderson you see above belongs to Jay Leno, who let me photograph it at one of the Hansen Dam Norton gatherings. Incidentally, if there’s a nicer guy than Jay Leno out there, I haven’t met him. The man is a prince. He’s always gracious, and he’s never too busy to talk motorcycles, sign autographs, or pose for photos. You can read about some of the times I’ve bumped into Jay Leno at the Rock Store or the Hansen Dam event right here on ExNotes.

Very early vintage motorcycles’ mechanical complexity is almost puzzle-like…they are the Gordian knots of motorcycle mechanical engineering design. I photographed a 1913 Thor for Motorcycle Classics (that story is here), and as I was optimizing the photos I found myself wondering how guys back in the 1910s started the things. I was able to crack the code, but I had to concentrate so hard it reminded me of dear departed mentor Bob Haskell talking about the Ph.Ds and other wizards in the advanced design group when I worked in the bomb business: “Sometimes those guys think so hard they can’t think for months afterward,” Bob told me (both Bob and I thought the wizards had confused their compensation with their capability).

There’s no question in my mind that water cooling a motorcycle engine is a better way to go from an engineering perspective. Water cooling adds weight, cost, and complexity, but the fuel efficiency and power advantages of water cooling just can’t be ignored. I don’t like when manufacturers attempt to make a water-cooled engine look like an air-cooled engine with the addition of fake fins (it somehow conveys design dishonesty). But some marques make water cooled engines look good (Virgil Elings’ comments notwithstanding). My Triumph Speed Triple had a water-cooled engine. I think the Brits got it right on that one.

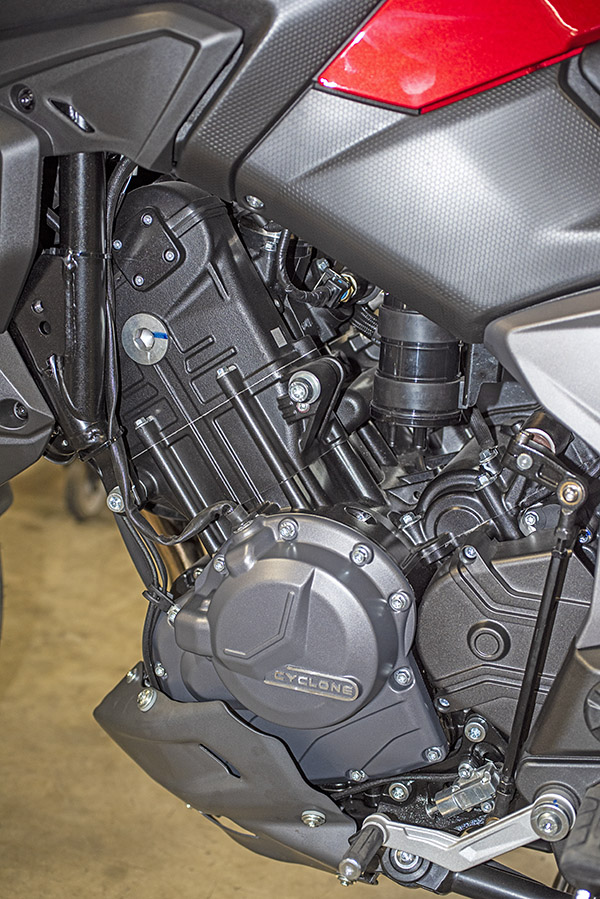

Zongshen is another company that makes water-cooled engines look right. I thought my RX3 had a beautiful engine and I really loved that motorcycle. I sold it because I wasn’t riding it too much, but the tiny bump in my bank account that resulted from the sale, in retrospect, wasn’t worth it. I should have kept the RX3. When The Big Book Of Best Motorcycles In The History Of The World is written, I’m convinced there will be a chapter on the RX3.

With the advent of electric motorcycles, I’ve ridden a few and they are okay, but I can’t see myself ever buying one. That’s because as I said at the beginning of this blog, for me a motorcycle is all about the motor. I realize that’s kind of weird, because on an electric motorcycle the power plant actually is a motor, not an internal combustion engine (like all the machines described above). What you mostly see on an electric motorcycle is the battery, which is the large featureless chingadera beneath the gas tank (which, now that I’m writing about it, isn’t a gas tank at all). I don’t like the silence of an electric motorcycle. They can be fast (the Zero I rode a few years ago accelerated so aggressively it scared the hell out of me), but I need some noise, I need to feel the power pulses and engine vibration, and I want other people to hear me. The other thing I don’t care for is that on an electric motorcycle, the power curve is upside down. They accelerate hardest off a dead stop and fade as the motor’s rpm increases; a motorcycle with an internal combustion engine accelerates harder as the revs come up.

Wow, this blog went on for longer than I thought it would. I had fun writing it and I had fun going through my photo library for the pics you see here. I hope you had fun reading it.

Never miss an ExNotes blog: