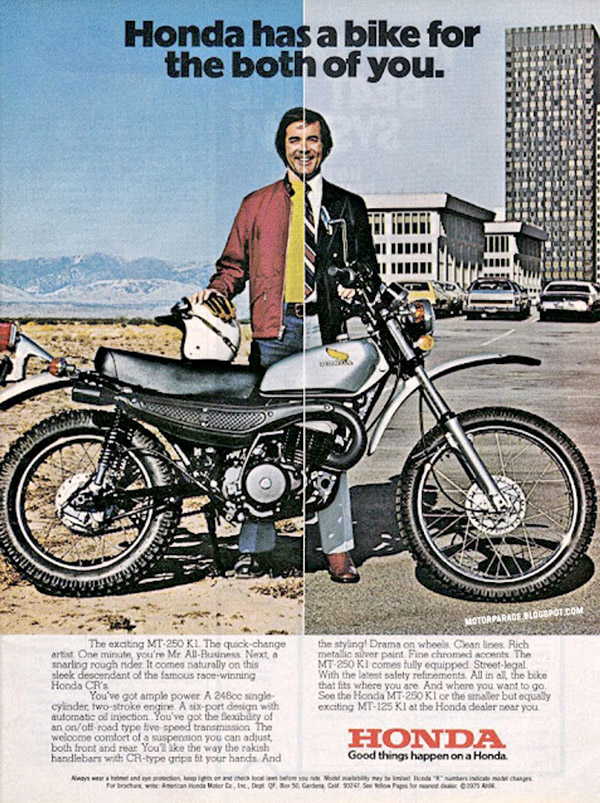

My Dad and I saw our first Honda ever in 1964 at a McDonald’s in East Brunswick, New Jersey. It was a 150cc Dream, the smaller version of the bigger CA 77 305cc Dream. I was 12 years old at the time. In those days, it was a fun family outing to drive the 20 miles to Route 18 in New Jersey and have dinner at McDonald’s (that was the closest one), where hamburgers were 15 cents and the sign out front said they had sold over 4 million of the things. And the Honda we saw that day…Dad and I were both smitten by the baby Dream, with its whitewall tires, bright red paint, and the young clean cut guy riding it. True to Honda’s tagline, he seemed to be one of the nicest people you could ever meet (although admittedly the bar wasn’t very high for nice people in New Jersey).

Keep us in clover…please click on the popup ads!

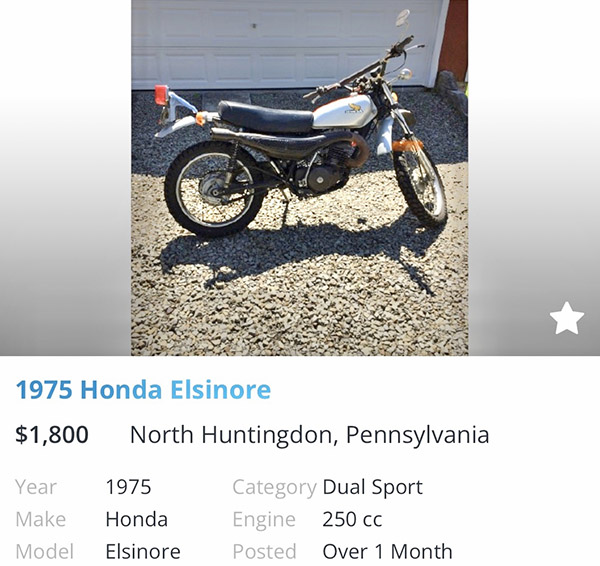

Dad and I started looking into Hondas, and that included a trip to Cooper’s Cycle Ranch near Trenton. Back then, it really was a ranch, or at least a farm of some sort…the showroom was Sherm Cooper’s old barn. The little Hondas were cool, but the big ones (the 305s) were even cooler. A 305 was the biggest Honda available in the mid-1960s and Honda imported three 305cc motorcycles to America: The CA 77 Dream, the CB 77 Super Hawk, and the CL 77 Scrambler. The Dream was not designed to be an off road motorcycle (that was the CL 77 Scrambler’s domain) or a performance motorcycle (in the Honda world, that was the CB 77 Super Hawk).

Of the 305 twins, It’s probably appropriate to discuss the CA 77 Dream first. The Scrambler and the Super Hawk were intended to appeal to motorcycle enthusiasts; the Dream was a much less intimidating ticket in (into the motorcycle world, that is). The typical Dream buyer was either someone stepping up from a smaller Honda, or someone who had not previously owned a motorcycle.

Honda first used the name “Dream” on its 1949 Model D (a single cylinder, 98cc two-stroke). No one knows for sure where the Dream moniker came from, but legend has it that someone, upon first seeing the Model D, proclaimed it to look like a dream. The C-series Dreams first emerged in Japan in 1957. Pops Yoshimura built Honda engines with modified production parts that ran over 10,000 rpm for 18-hour endurance races, proving the basic design was robust. Some say Honda based the engine design on an earlier NSU engine, but Honda unquestionably carried the engineering across the finish line. Whatever. When’s the last time you saw an NSU? Another big plus was that Honda used horizontally split cases and that (along with vastly superior quality) essentially eliminated oil leaks. The other guys (and in those days, that meant Harley and the Britbikes) had vertically split cases and they all leaked. Honda motorcycles did not, and that was a big deal for a motorcycle in the 1960s.

There were several differences between the Dream and the other two Honda 305cc motorcycles. The Super Hawk and the Scrambler had tubular steel frames and forks; the Dream used pressed steel for both its frame and fork. The Dream was a single-carb motorcycle; the Super Hawk and the Scrambler had twin carbs. The Dream had large steel valanced fenders, the other Hondas had more sporting abbreviated fenders. The Dream was the only 305 that came from the Honda factory with whitewall tires. The Dream had leading link front suspension; the Scrambler and the Super Hawk had telescopic forks. The Dream used the Type II crankshaft (so did the Scrambler) with a 360-degree firing order (both pistons went up and down together, but the cylinders fired alternately). The higher performance Super Hawk had the Type I, 180-degree crankshaft. Like the Super Hawk, the Dream had electric starting (the Scrambler was kick start only). The Dream came with a kickstarter, too, but why bother? I mean, you weren’t going to be mistaken for Marlon Brando when you rode a Honda Dream.

The Dream’s 305cc engine had a single 23mm Keihin carb and it produced 23 horsepower at 7500 rpm (not that the rpm was of any interest; the Dream had no tachometer). With its four-speed transmission and according to magazine test results, the Dream was good for between 80 and 100 mph (depending on motojournalist weight, I guess). The Dream averaged around 50 mpg, although in those blissful days of $0.28/gallon gasoline, nobody really cared. Honda Dreams came in white, black, red, or blue. With 20/20 hindsight, I wish I had bought one in each color and parked them in the garage. My favorites were black or white; those colors just seemed to work with the Dream’s whitewall tires.

Honda built the Dream until 1969. The Dream retailed for $595 back in those days, but a shrewd negotiator could do better.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

See our other Dream Bikes here!

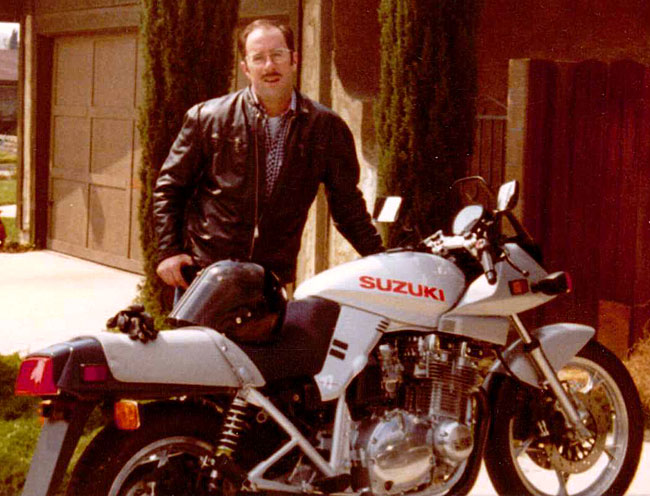

It’s not every day you get to see a new 2020 Suzuki Katana for the first time, and it’s certainly not every day you get living legend and motojournalist extraordinaire Kevin Duke to take a photo of you standing next to it. Yesterday was that day for me, and the photo you see above was a shot Kevin grabbed of yours truly with the new Katana. I was visiting with the boys at

It’s not every day you get to see a new 2020 Suzuki Katana for the first time, and it’s certainly not every day you get living legend and motojournalist extraordinaire Kevin Duke to take a photo of you standing next to it. Yesterday was that day for me, and the photo you see above was a shot Kevin grabbed of yours truly with the new Katana. I was visiting with the boys at