By Joe Berk

Full disclosure up front: I’m a longtime contributor to Motorcycle Classics magazine, and I love reading every issue. Every time I read the latest edition I think they’ve outdone themselves (both with the writing and the photography) and I wonder how they are going to top it in the next edition. And then they do. Full color, full page, lots of pages, and high-quality paper. About the only other magazine that has managed to keep the doors open and continue to do a similar high-quality job is RoadRUNNER. I’ve written for RoadRUNNER in the past, too, and you might be wondering if maybe I am a little bit biased. I am not a little biased; I am a lot biased. I love both these magazines.

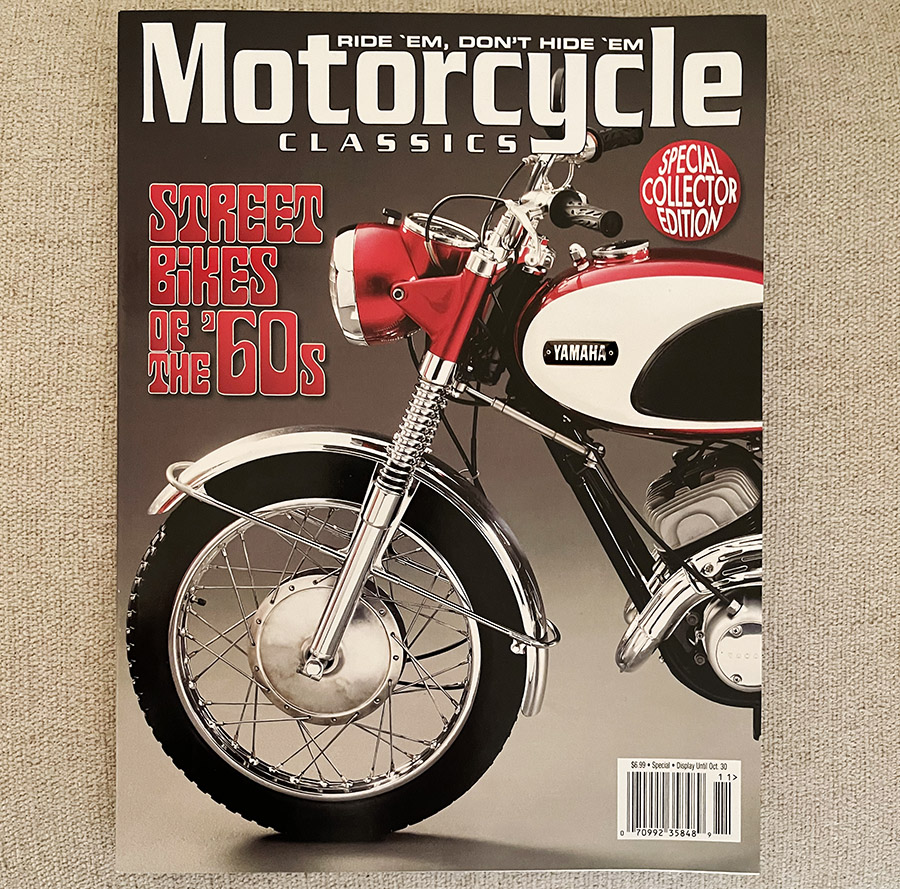

Every so often Motorcycle Classics will publish a compendium of stories from past issues on a specific topic. I’d never purchased any of these until recently, and then I picked up two of them: Classic Bikes of the ’60s, and Classic Road Trips. This review is focused on Classic Bikes of the ’60s. We’ll publish a separate review on Classic Road Trips in the near future.

About now you might be wondering: Why buy the special editions? If you have been buying the magazine all along, wouldn’t you have each of the stories in those back issues? The answer, of course, is yes. But for just a few bucks, I’ve got all the stories concentrated in one place, and I don’t have to go digging through 6 feet of shelf space and a couple of hundred issues to find a particular story.

Classic Road Bikes of the ’60s is, for me, indeed a special edition. I came of age in the ’60s, and the stories in this issue are on the bikes I lusted for when I was a teenager. Every bike is one I dreamed about, and wow, they’ve got some great stories in this edition. It has feature pieces on these motorcycles:

-

- 1967 BSA Spitfire (one of the most beautiful motorcycles ever made, in my opinion…like the one Tommy Smothers rode back in the day)

- 1966 Honda Dream (I recently wrote about the Dream, too, in this same magazine…Gresh owned three of them).

- Velocette Thruxton (the stuff of dreams, truly one of the world’s stunning motorcycles)

- 1969 Ducati 350 (I confess…I never quite got the fascination with Ducati, but hey, there’s no accounting so for some folks’ tastes)

- 1962 BMW R60/2 (in creamy white with black pinstripes, which is magnificent)

- 1963 Royal Enfield Interceptor (the grand-daddy of my current bike…a kid I knew in high school had one of these).

- 1961 Harley Duo Glide (the look that inspired a generation of Harley designs, and one that has never been matched)

- 1966 Honda CB450 (the black bomber; great technology, atrocious styling)

- 1967 Triumph Bonneville (absolutely the most beautiful bike in the world, with a sound to match)

- 1965 Bultaco Metralla (I once had a friend who though a Bultaco was something you eat)

- 1966 Norton P11 (also commonly referred to as the Norton Scrambler, it was the 750cc Atlas engine in a Matchless 500cc frame)

- 1969 Kawasaki 500cc Triple (ah, an awesome machine…I rode alongside a guy who had one of these on my first international motorcycle ride back in 1969)

- 1973 Moto Guzzi V700 (close enough to the ’60s to be included here…I always wanted one…they sound more like a Harley than a Harley does)

- 1968 Yamaha Big Bear Scrambler (this one is so beautiful it graces the cover of the special edition magazine)

- 1968 Triumph Trident T150 (too little too late…it couldn’t compete with Honda’s CB750, but it was nice)

- 1969 Norton Commando (a “Parting Shots” story about a ride on the famed commando)

Classic Road Bikes of the ’60s is a great read and a worthwhile reference. Like I said above, you’re getting great photos, great writing, and great entertainment. When you buy your copy, I’m certain you’ll agree.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

Don’t forget: Visit our advertisers!