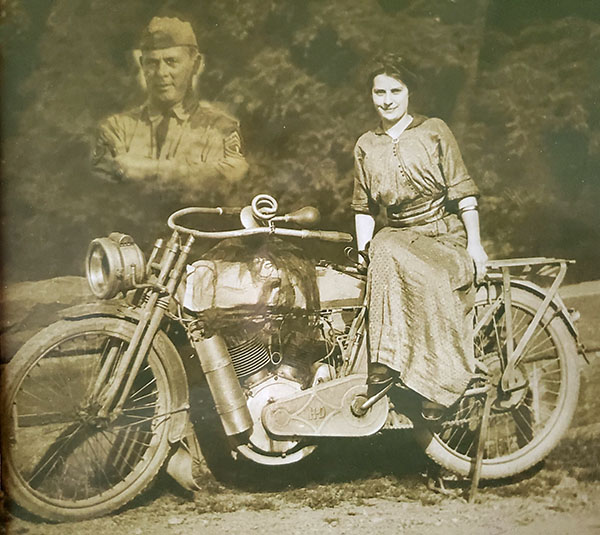

Jack Lewis and I platooned in Motorcyclist magazine for many years. How Jack managed to avoid writing about concrete in all that time I’ll never know. Here’s a bit on lane splitting for America.

Dear automobilists – you, in the shiny red pickup and that girl in the flashy BMW and yes, even you in the dented Subaru with the sticker-patched Yakima box up top and dog slobber lathering your windows – please don’t misunderstand us.

When we rip along the dotted lines, zipping between door handles in a manner that must look crazy-dangerous to you, we’re not actually trying to rub your noses in the hell of stop-and-go traffic. We’re not trying to cheat you out of your transportative birthright, nor play some weird Russian roulette with spit cups and trailer mirrors.

We’re just trying to get out alive.

See, while you may perceive motorcyclists mostly through GoPro silliness and X-Games heroics, a lot of riders actually give real thought to which measures might bring us through our riding day intact, arrayed as we are with nothing but a bit of thick foam and thin plastic between our squishable bodies and your 3,500 lbs. of moving steel.

Still, I get what it’s like to be startled, whilst sitting in my car, by a motorcycle howling past in a sudden rush. It’s a little spooky, and I always feel like I should have been paying better attention.

That’s how you feel, right? Like you should have been paying better attention?

Sure ya do! Just before you wonder out loud why anyone let those irresponsible dingbats loose on their murdercycles in the first place. How dare they discompose you, let alone proceed at a pace slightly faster than the turgid sloth of gridlock?

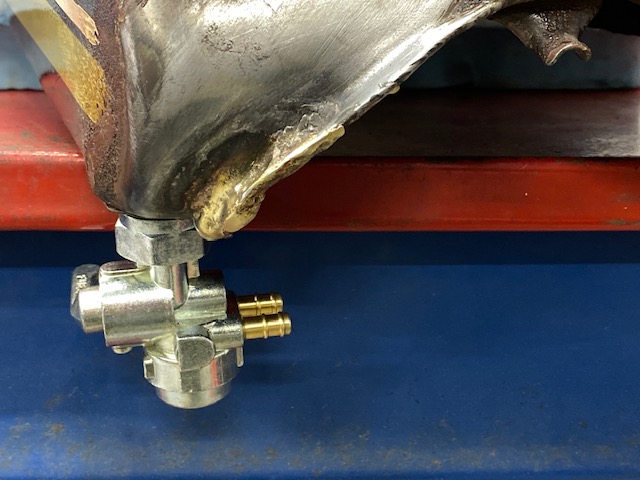

Being stuck in traffic is ugly for everyone. On a motorcycle, it’s worse. Yes, your kids may be fighting in the back seat, but they were gonna do that, anyway. The biker is juggling variables that include overheating, keeping his bike upright, clutch wear, where to put his feet (Pegs? Ground? Pegs? Ground?), and the friction-free contact patches ensured by the overflowing coolant of pissed-off cars.

Motorcycles are built to go, and they’re built elementally light. While your car does its engineered best to trade off its BTUs to the surrounding atmosphere on a hot day, and swaddles you in a full metal jacket against winter rain and snow, that rider tap dancing along the Botts’ dots either needs continuous air flowing over her engine to keep both it and her body from overheating, or would very much like to get home and take Mom’s advice to get out of those wet things. Hypothermia is a risk they cover in basic riding classes.

Serves those fools right, you say? Fine, but remember: if the motorcycle breaks down and has to be pushed out between the choked lines of traffic to meet a tow truck, that ain’t exactly gonna speed you up.

If the driver behind a stuck rider gets distracted by the radio or her kids or a super-important tweet, she may roll up into the rider who obediently parks between cars, virtually disappearing in a long line of tail lights. Or some other driver may spot a “hole” in the next lane, yank over and park on our hapless moto-jockey. Aside from the bloody consequences for some poor dumb motorcyclist, that accident holds up traffic even longer while EMTs slowly wail their way up the breakdown lane.

But isn’t it dangerous for those guys to go between the cars, where nobody can see them coming? Well, if you actually use your mirrors, you can see bikes much better when they’re moving between the lanes. Our eyes are designed to notice movement and anomalies.

Moreover, in any accident occurring between your car and a motorcycle, it won’t matter one bit how the lawfully the rider was behaving, or how badly you screwed up. All you have to say is “I never saw him,” or, “He came out of nowhere!” Once you’ve articulated those magic words, your police report will reliably read “DRIVER NOT CITED” — even if you blew a red light, made a left against traffic, or ran him down from behind. Tuck that knowledge away for later use, because it. Is. Awesome.

It’s even kind of true. Even with decades of motorcycling under my (continuously expanding) belt, I’ve overlooked motorcycles from behind the wheel. No one can see bikes as well as cars. You can’t judge their distance effectively whether they’re coming (only one headlight) or going (only one taillight). At night, they’re practically invisible and during the day, they may as well be.

Cars and trucks grow logarithmically in your vision as they approach, while bikes are always just… small. Your brain doesn’t process them as a real vehicle, and the courts know that. Killing a motorcyclist is kinda like hitting someone’s beloved terrier: the family may be broken up about it, but everybody else understands that it wasn’t really your fault.

We implore you not to use this powerful knowledge to hit the next rider you see, though, as it will definitely slow down your commute. We’re talking efficiency here.

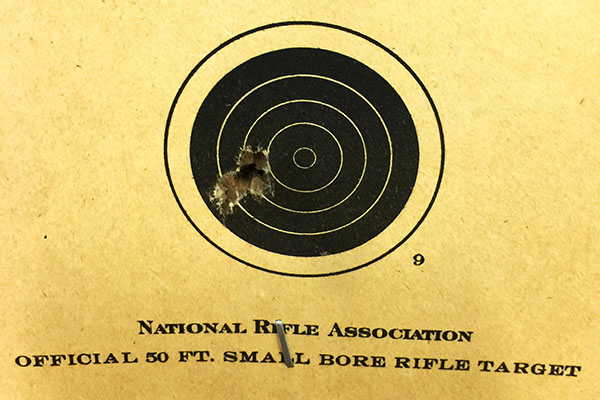

You can’t see them, but they can see you. Lane splitters keep an eye on your movement the way mice watch owls, and they won’t carelessly ding your car. Think about it: catching a handlebar end means they go face down on the freeway. Nobody volunteers for that.

Lane-splitting motorcyclists tend to be well-trained, fit, decently equipped riders, and they’re statistically safer than riders who never split lanes.

Kinda flies in the face of common sense, dunnit? But then, so does motorcycling. Not everyone wishes to be common, or sensible.

We know it seems like cheating for them to weave through the blocked ranks of Good Suburban Taxpaying Folk – and it is. If you ain’t cheatin’, you ain’t tryin’.

That’s why you get to do what bikers can’t: control your climate with dashboard switches, sip the beverages nesting in your cup holders, flip through the FM dial for Sigalerts, call your sweetie through the rear view mirror (that you never glance at) with a dinnertime update, and scroll GPS maps for the clearest route. If you’re unwilling to give up your car full of traffic hacks and blissful comforts, why should riders sacrifice their ability to proceed elegantly through smaller spaces?

As second-class traffic citizens, speed, wariness, and maneuverability are the only tactical advantages motorcyclists possess. Don’t think of them as a safety threat to your armored carapace. They’re more like furry little rodents, juking between the footfalls of mighty dinosaurs.

“Fair” is a utopian concept and you can’t get to Utopia from here. What you can get is home a little faster, every time a rider splits lanes. Think this through with me: when a rider lane-splits, he transcends the traffic jam, flowing through it with mercurial ease while you sit there, stymied and cursing your ugly luck. Advantage: rider. Kinda gets your goat, doesn’t it? They shouldn’t be able to do that!

But wait… she also removes one vehicle from the impacted sludge of traffic. Advantage: EVERYBODY. Will you receive a benefit equal to the rider’s? Nope. She assumes more risk, makes less ecological impact, trades comfort for freedom and burns less fuel. Seems only fair that she should get through the fastest. Let ‘er go, mate. Don’t swing that door out!

When two percent of vehicles slip out of the traffic stream and split lanes, that’s two percent fewer vehicles getting in your way, threatening your family’s safety, and farting their carbon monoxide straight through your cabin filter and into the soft, vulnerable fat of your cerebral cortex. Can you imagine if it were 15, 20, or as much as 50 percent of traffic that was bled off by those dynamic pressure relief valves? Lane splitting makes riding more attractive, increasing the number of people willing to deal with the disadvantages.

We all know what causes traffic jams: too many vehicles occupying the same road space at the same time. One social engineering tool to purge that clog is HOV lanes allowing more efficient transport – e.g. buses, motorcycles, and carpools – to move faster. Studies show that such lanes also speed up main lines of traffic. Still, it’s danged annoying to watch privileged eco-prudes whiz by in their Teslas, and we all know it costs tens of millions of your dollars to build those lanes that you usually can’t use.

When interstate flyers shine on the dotted line, though, three or four de facto diamond lanes spring up at no cost — but offer benefits to every vehicle’s progress, from buses to Jeeps to Peterbilts.

And in town, when scooters and motos slip between cars and filter up to the front of an intersection, they’re not ripping you off. When the light changes they’ll accelerate celeritously, maneuvering between late-walking pedestrians without risk. Then they’re gone and out of your way, cutting down both on your total sum of obstacles and on the safety variables you have to reconcile.

Poof! They just vanish, right off your cloud. You won’t have to navigate cautiously around their wobbling butts the way you do with bicycles. Also (unlike those free-loading pedalers), motorcyclists pay disproportionately high license tag fees to help maintain your roads.

No one is harmed, and everybody wins. Ever wish a whole bunch of drivers would just get off your damn road? Yeah. It’s like that.

Traffic works better when we all work together. No man is an island, entire of itself. Therefore, ask not for whom the rider lane-splits; she splits for thee. Next time you’re asked, vote to allow lane-splitting in your state for the benefit of every driver… and the true safety of every rider.

If you still think all lane-splitting does is give a huge advantage to motorcycles, why not ride one yourself? Nothing prevents you from stepping out of your big, safe box, swinging your leg over a bike, and winging it through traffic in swift, sexy, highly maneuverable freedom.

Do it for yourself. Do it for society. All you have to fear is fear itself — plus, of course, the savage vindictiveness of unenlightened drivers (no, don’t be that guy; nobody likes that guy).

So come on over the dark side. We throw the best parties – and you’ll get there fast, looking fly on your bad motor scooter.

Everybody wins.

If you’d like to see more Jack Lewis, you can do so here on his blog.