By Joe Berk

I recently posted a couple of blogs about Death Valley, including a recap of my several visits over the last decade. This blog is a little bit different. it’s about some of the cool stuff near Death Valley. I didn’t have any hard rules about how close “near” means. I’m including the places I’ve visited and thought were worth a mention. If you think there should be more, leave a comment and tell us about it. We love hearing from you and we love when you click on the popup ads, so don’t forget to do so (and when you see that donate button at the bottom of this blog…well, you know what to do).

I shot most of the photos in this blog with my Nikon D810 and the 24-120 Nikon lens. A few were with the Nikon N70 film camera I recently wrote about, and where that is the case, I’ll say so in the photo caption.

Baker

When visiting Death Valley from the south (as in southern Calilfornia), it’s likely you’ll pick up Highway 127 in Baker, just off Interstate 15. There used to be a hotel in Baker, but it’s gone. There are a couple of gas stations a couple of tacky fast food franchises, but don’t waste your time eating in a fast food franchise. What you want is the Mad Greek.

I didn’t eat at the Mad Greek on this trip (either coming to or leaving Death Valley). Sue decided several trips ago she didn’t like the place, so I deferred to her wishes. I never know when I might want to buy more reloading components, another gun, another watch, or another motorcycle, so we took a pass on the Mad Greek (Sue is of Greek ancestry; maybe that has something to do with it). When I ever pass through Baker on my own, though, the Mad Greek is a sure thing.

The other thing Baker is famous for is its thermometer. It’s 134 feet tall, in honor of reaching that record temperature in 1913 (I guess we had global warming back then, too). If you go through Baker, you have to get a photo of the Baker thermometer. It’s a rite of passage.

Highway 127

The ride north through the California desert from Baker to Death Valley is both beautiful and historic. It follows the Old Spanish Trail, something I had never of until I saw the signs and did a little research. Established in 1829, the Spanish Trail is a 700-mile long road that runs from Santa Fe to southern California. It traverses New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, and California. John C. Fremont and Kit Carson used it. Serapes and other woven goods went to California from New Mexico; California’s horses and mules went to Santa Fe. Indian slaves, contraband, and more used this same route.

Shoshone

The first time I ever visited Shoshone was on the Destinations Deal ride. I remember well the terror I felt on that stretch of road, leading a group of other riders after a long day through Death Valley. We were heading south on Badwater Basin Road and I was relying on my cell phone and Waze to guide me. I was worried about running out of gas, keeping one eye on the gas gage and the other on the road. I should be okay, I kept thinking, but I’d never been this way before and I didn’t know. Then my Waze program quit. It had been running on stored info because I had no cell phone reception for the last 60 or 70 miles. The gas gage was nudging closer to the “no more” line and I was sweating bullets. It sure was remote out there.

Finally, Highway 178 ran into Highway 127 and a sign pointed to Shoshone. I felt better, and then I realized I didn’t have the Shoshone Inn’s address where we would spend the night. “How will I find it?” I wondered. It wouldn’t be easy leading other riders while looking for the place (I’ve had to do this on other rides). Then I was suddenly in Shoshone and I started to laugh. You can’t miss the Shoshone Inn. It’s one of only three or four buildings. I’d say Shoshone was a wide spot in the road, but California 127 was no wider there than it was anywhere else.

Shoshone was founded by Ralph Fairbanks in 1910; initially, it was primarily a mining town (old Ralph was a Death Valley prospector and entrepreneur). Charles Brown (yep, Charlie Brown) married Fairbanks’ daughter. Charlie and Stella moved away, but they returned in 1920 and further developed the town. Charlie became a California state senator and he turned ownership of Shoshone over to his son (who was also named Charles Brown). I guess you might say Shoshone is a Charlie Brown kind of place. I been there a few times, always looking for a girl named Lucy, but so far, I’ve had no luck.

As I mentioned in an earlier blog, the Population 31 sign lied. It’s only 13 people now. The lady who runs the hotel (Jennifer, not Lucy) commutes from Pahrump (Pahrump is about 45 minutes east on the other side of the Nevada state line). She told us about the sign lying. The rest of the people either died or moved away. None of them were named Lucy.

Shoshone is the last town before the southern entrance to Death Valley National Park. One woman, a Mrs. Sorrells, inherited the town. There’s a school that handles kids from K through 12th grade, some of whom commute from up to 120 miles away. There’s a general store (including a gas station), a museum, a restaurant (the Crowbar Cafe and Saloon), a nature trail, an RV park, and an unmanned airstrip. I guess if you are flying to Shoshone, you have to make a pass or two over the runway to make sure it’s clear.

The Shoshone Inn

The Shoshone Inn is surprisingly nice, although it’s probably time for it to be refurbished. There’s a gas-fired fire pit outside in the unpaved parking lot; when I rode into Shoshone with the Destinations Deal crew we spent a nice evening drinking Joe Gresh’s beer, which he bought from Shoshone’s next-door Charles Brown general store.

I got up early the next morning to take pictures with my film camera (the N70 my sister gave to me) and I saw that the fire pit was still going; I think the Shoshone Inn desk clerk may have forgotten to turn it off (they will be surprised when they get their gas bill).

The Charlie Brown Rocks

When I Googled what else was around Shoshone, the Charlie Brown rocks appeared. Highway 178 east intersects with Highway 127 right at the southern edge of Shoshone. When I saw the Charlie Brown rocks on Google, I wasn’t sure how far east on 178 I’d have to go, but when I approached Shoshone, I saw it was not far at all. The rocks are what appear to be sandstone formations and they are kind of in your face as you approach Shoshone. I could see the cave openings I’d read about, but there were signs to ward off trespassers and I didn’t want to wander in. A few photos were good enough.

The Crowbar Cafe and Saloon

Sue and I had two meals in the Crowbar. As I had experienced on previous visits (especially if you get there later in the day) it’s good to have three or four meal choices ready when the waitress takes your order. Hamburgers? No hamburgers, we had a busload of Chinese tourists come through and they ate all the hamburgers. Trout? No trout. Tacos? Yep, the Crowbar had tacos and they were surprisingly good.

When we left after lunch that first day, we spotted a small airplane on the runway at the town’s southern edge (the runway is tucked into the southeastern corner of the Highway 127/178 intersection). There’s no tower or buildings or anything else there, and you only see that it’s a paved runway when you look (you wouldn’t notice it otherwise). We think the four young guys who were sitting one table over from us at lunch flew in from somewhere to eat at the Crowbar.

We sat at the bar the next night and the one-man-band lady who handled everything (waitressing, barmaiding, dishwashing, etc.) asked if I wanted a beer. You bet, I answered. There were four taps, all unmarked. She didn’t know which tap had which beer, so she poured me a small sample of each and I opted for a craft-brewed dark beer. The bartender/waiter/dishwasher told me was made in nearby Tecopa. It was good, as were the chicken fajitas Sue and I shared for dinner.

The Shoshone Museum

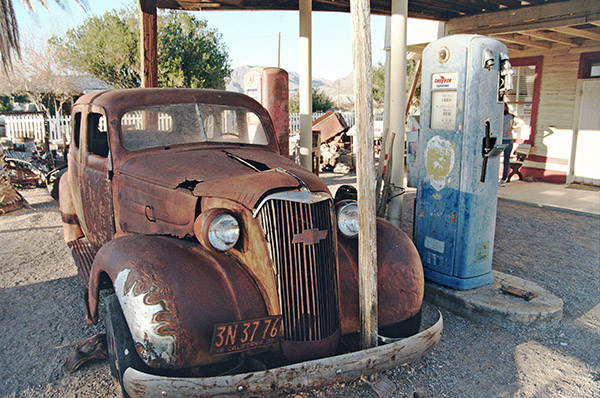

We didn’t go into the Shoshone museum because it was closed the two times we visited the Crowbar (it’s right next door). It didn’t look as if there was much there; it was all housed in a very small building. I took a picture of an old Chevy, an old fuel pump, and a bit of junk in front of the museum. I’m guessing the museum used to be a gas station. I’ll bet Charlie Brown owned it.

Tecopa Springs

Tecopa Springs is short drive east of Shoshone on Highway 178. We went there twice. We saw quite a few RVs but we only saw a few people in front of Tecopa’s two restaurants. A young fellow we spoke to at the Crowbar the previous night told us he lived in Tecopa for six months each year and worked remotely (he was a digital nomad like Mike Huber). I imagine he spent winters in Tecopa and found someplace cooler in the summer. He said he came into Shoshone once a week for dinner because he wanted fried food and he couldn’t make fried food in his RV.

The two restaurants in Tecopa are a barbeque place and a combined bar and pizza place. The digital nomad we spoke with in the Crowbar said Wednesday (the day we rolled into Tecopa for dinner) was the best night at the barbeque place, but that restaurant was closed when we rode by. We rode on to the beer and pizza palace. When we entered, I asked the guy at the bar about the dark beer I’d had the night before in Shoshone (which was made in Tecopa), but they didn’t serve that brew there. He gave me a small sample of their dark beer (also brewed in Tecopa). It had kind of a peanut flavor to it and I thought it was okay, but the beer the previous night was better. The bar only had two seats; there were other people drinking and smoking at tables outside the restaurant.

When I asked about their dark beer, the one guy who was seated at the bar told me,”it’s this one…the dick.” I wasn’t sure I heard him correctly until I looked at the tap (which I hadn’t noticed). It was, indeed, a dick. I had to grab a photo.

We ordered a pizza that seemed to take forever. When the guy finally brought it out, it was cold. It had probably sat for a while. Trust me on this: You wouldn’t want to make the trip to Tecopa for the pizza. Maybe the photo ops, but not the pizza.

There’s also a date farm somewhere beyond Tecopa. Sue and I rode out there after dinner, but it closed at 5:00 p.m. and we were too late. They had date shakes and I was looking forward to one, but that will have to wait until my next visit.

The Amargosa Opera House

After poking around a bit more on the Internet, I read about the Amargosa Opera House in Death Valley Junction. It was 50 miles north of Shoshone. The pictures on the Internet looked like the Opera House theatre’s interior would make for an interesting photo stop, so I called a couple of days before. I mentioned that I was doing this for the ExhaustNotes website and possibly, a travel article for Motorcycle Classics magazine.

A young lady answered the phone and told me I needed to email their Director of Operations. She promised he would get back to me that day. That sounded like a plan and the Director of Operations did indeed get back to me with this message: I could take their daily tour (at a cost of $15 per person) or I could pay $500 for one hour to photograph the theatre. Gulp. I can’t remember ever paying anyone anything for something like this.

Sue and I rode to Death Valley Junction anyway, and I grabbed a few photos from the outside. When we first saw the place, it looked run down. It’s hard to believe anyone would stay their hotel, but I guess people do. A few photos and a $500 savings later, we were back on the road.

Pahrump

After spending another half day in Death Valley National Park, we decided to head over to Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area. That’s near Las Vegas. On the way over, we crossed into Nevada and entered Pahrump. Pahrump is a much bigger town than anything around Death Valley. It has been one of the fastest growing towns in the entire U.S., with 15% year-over-year population growth for each of the last several years. We thought Pahrump would be a good place to have lunch, and we were right.

Sue found a place called Mom’s on her cell phone, it had great reviews, and we had to wait a few minutes to get in (which is always a good sign). Trust me on this: If you ever find yourself in Pahrump, Mom’s is where you want to eat.

As I mentioned above, we went through Pahrump on our way to the Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area. I was going to squeeze that in here, too, but this blog is getting a little long. I’ll save Red Rock for another blog.

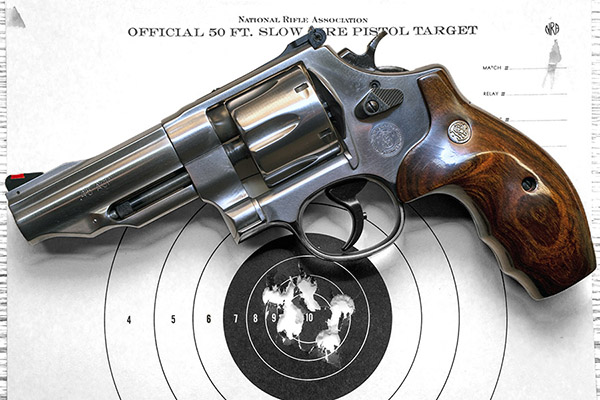

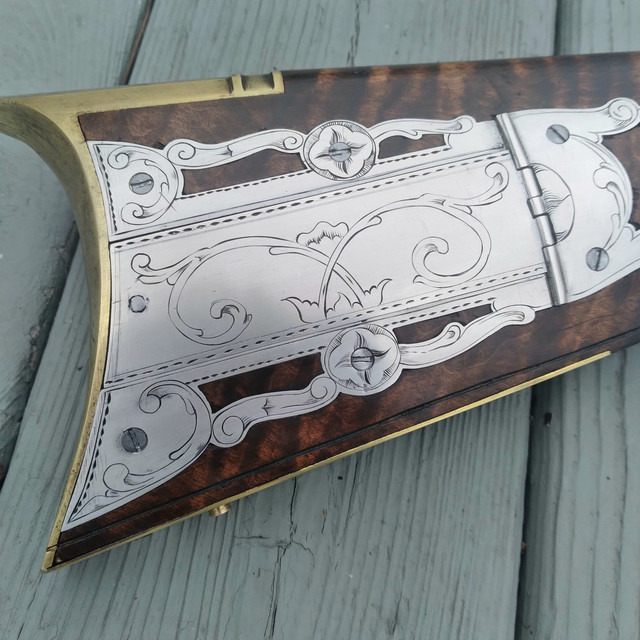

On the ride out of town on our way back to Shoshone, we stopped for gas in Pahrump. It was $3.68 per gallon. That’s a good two bucks cheaper than what we pay in California. After filling up and on the way out of town, we saw a gun store creatively named Pahrump Guns and Ammo. Sue won’t let me drive past a gun store without stopping, so we did. It was a small place and we had a nice visit with the two guys who worked there. I told them we were from California and we were collecting campaign contributions for Hillary Clinton. We had a good laugh. People in Pahrump have a sense of humor.

Barstow’s Del Taco Restaurants

You probably think I’m crazy including the Barstow Del Taco restaurants in this blog. I’m listing it here because if you’re going to Death Valley from southern California, it’s a safe bet you’re going to pass through Barstow, and if you’re going to pass through Barstow, you need to stop at one of the three Del Tacos there.

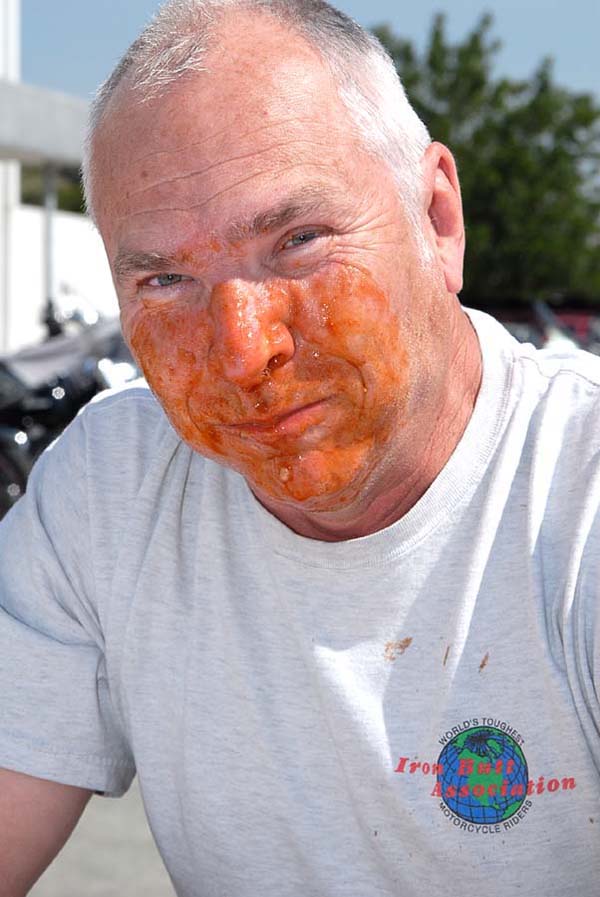

There’s a story behind this. About 15 years ago I had a bad motorcycle crash and I had to spend a month in the hospital. One of the guys I shared a room with was the son of Ed Hackbarth, the entrepreneur who founded the Del Taco restaurant chain.

Ed Hackbarth is a real prince of a guy. He started Del Taco in Barstow, the restaurant chain was riotously successful, and it spread all over the U.S. Ed sold the Del Taco chain way back in 1976 to a group of investors and it continues to thrive. But there’s a big difference between the rest of the Del Taco empire and the three Del Tacos in Barstow. When Ed sold Del Taco, part of the deal was that he kept the original three Barstow Del Tacos. Ed would continue to use the Del Taco name on those three restaurants, but he didn’t have to use the Del Taco menu and he could serve food the way he wanted. And that’s what Ed does. The portions are bigger (they’re huge, actually), everything is fresh (nothing is ever frozen), the restaurants are immaculate, and the staff is super friendly. The Barstow Del Tacos have some of the best tacos and burritos I’ve ever had. We won’t drive through Barstow without stopping at one of Ed’s three Del Tacos, and there’s been times we’ve made the 80-mile trek from my home to Barstow just for a taco. You should try one. You can thank me later.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

Here’s that image with its levels and curves adjusted:

Here’s that image with its levels and curves adjusted: