By Joe Berk

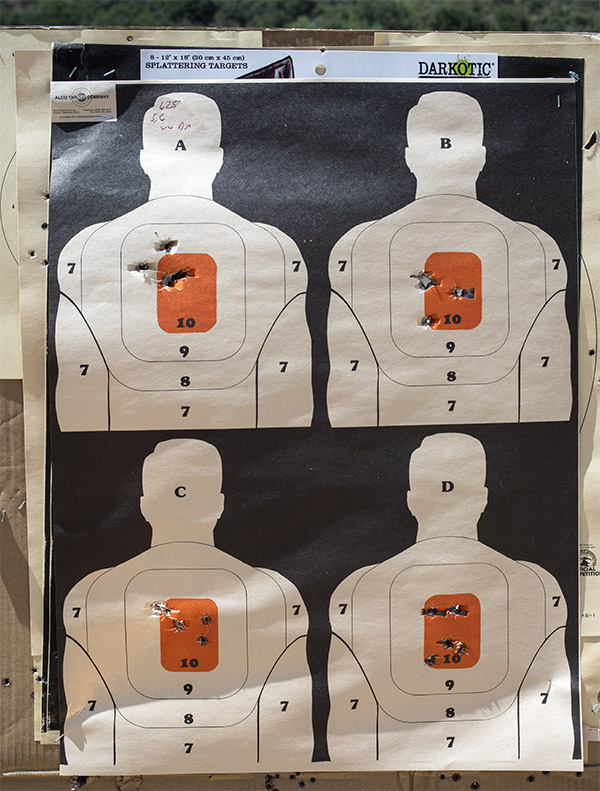

When most folks think of the .45 ACP cartridge, they think of the 1911 and other semi-auto handguns. The big .45 also makes an ideal wheelgun cartridge, especially in N-frame Smith and Wessons. I own four (the ones you see above) and I shoot them all.

The .45 ACP Revolver Story

Smith and Wesson forayed into the .45 ACP revolver business when Colt couldn’t keep up with the demand for its 1911 semi-auto in World War I. The Army asked both Smith and Colt to make .45 ACP versions of their large-frame double action handguns, both manufacturers did, and the Army designated both revolvers as the Model 1917.

After the World War I, the 1917 revolvers became available to civilians. Colt left the .45 ACP revolver business, but Smith and Wesson soldiered on, and to this day Smith still offers several different models.

Shooting .45 ACP ammo in a revolver requires a clip. You have to snap the rounds into the clip so they will fire and extract in a revolver. At one point, the 1917 revolvers were popular enough that Remington introduced the .45 AutoRim cartridge, which is a rimmed version of the .45 ACP that allows use of the cartridge in a revolver without the clip.

Over the years Smith and Wesson has manufactured several .45 ACP revolver models. I’d like to own them all, but there’s only so much room in the safe and Susie’s willingness to indulge my gun collecting. The four this blog addresses are:

-

-

- The Model of 1955

- A Jovino snubnose

- Smith’s reincarnated and Turnbull-finished Model 1917

- The Performance Center Model 625.

-

Info on each follows.

The Model of 1955

Smith introduced the Model of 1955 as an alternative to the 1911 semi-auto for bullseye target competition. Mine was made in the 1970s. I bought it from Rutgers Guns in Highland Park, New Jersey shortly after I left the Army (Rutgers Guns had no connection to Rutgers University other than geography). I paid around $200 for it new.

The Model of 1955 has Smith and Wesson’s target trigger and target hammer, and it has target sights (with a Patridge style sight in front). It originally had checkered grips, but shortly after I bought it I put a set of smooth grips on it. I think the smooth grips both look and feel better. Back in the day, you could purchase those grips new for around $25. Today, a set from that era (like the ones you see above) would fetch $300 to $400. The Model of 1955 has the highly polished and deep blue finish that is the hallmark of earlier Smith and Wesson revolvers. It is a beautiful handgun.

I never tried a load in the Model of 1955 that didn’t do well; every powder and every bullet combination I loaded grouped well. In the nearly 50-years that I’ve owned this revolver, I’ve only seen one other guy on the range with the same gun. I asked him what load he used and he told me the gun likes everything; every load he ever tried shot well, too. That said, the load I use is typically 4.2 grains of Bullseye and a 200-grain semi-wadcutter bullet. I use Lee’s Deluxe 4-die set and I crimp the bullets with their factory taper crimp die to assure easy chambering and to prevent bullet pull under recoil (although recoil with this load is light).

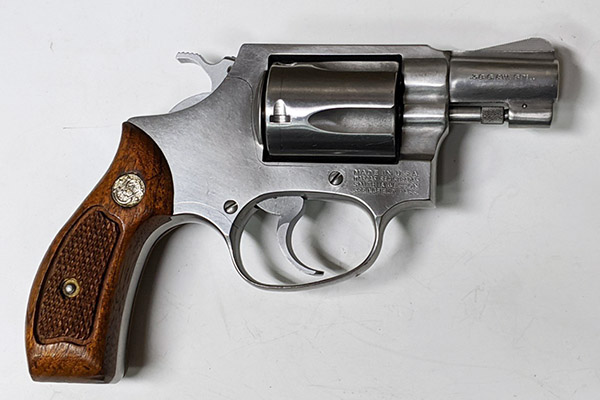

The Jovino Snubbie

The Jovino snubnose revolver is a rare animal, one of 650 customized by New York City’s John Jovino Gun Shop (which no longer exists; when it closed, Jovino was the oldest gun shop in the country).

Back in the 1980s, Jovino’s built custom guns. Their main clients were the NYPD and other police departments, so many of the Jovino customs tended to be duty-oriented carry weapons. Jovino bought 6 1/2-inch barreled Smiths like the one you see above and turned them into 2 1/2-inch snubnose revolvers. The conversion was not just a simple chop job, though. Here’s what Jovino did to these guns:

-

-

- Shortened the factory barrel to 2 1/2 inches.

- Installed a crane lock to replace the ejector rod lock.

- Relocated the red ramp front sight.

- Rounded the butt to the S&W K frame round butt configuration.

- Tuned the double and single action trigger.

- Radiused the hammer spur.

- Polished the trigger face.

- Fitted Pachmayr rubber grips.

- Reblued the cut barrel (the new bluing is actually a bit darker and more polished than the stock bluing).

-

The original grips that came with the Jovino snubbie were rubber Pachmayrs, but I wanted the look of ivory grips. That’s when I found out that the Jovino guns did not have a standard N-frame rounded grip profile. It took a lot of patient sanding and polishing to get the fake ivory grips to fit. I like the look.

The double action trigger on the Jovino is incredibly smooth. The slick trigger and the red ramp and white outline sights work together well, and the gun is very accurate. I’ve never seen another one of these guns on the range, so the exclusivity factor is there, too.

Smith and Wesson’s Reincarnated 1917

About 20 years ago Smith and Wesson introduced a reissue of its World War I Model 1917 for a very short time, and as part of that deal, the new Smith included Turnbull color case hardening. I saw one of the Turnbull 1917 revolvers at a local Bass Pro and it sat in the display case for months. Bass Pro had it marked down to $695 and it still hadn’t moved. I asked the kid behind the counter what they would take for it; he read the price tag and told me $695. Would you consider less, I asked. I’d have to ask the manager, he said, looking at me and not moving. Why don’t you do that, I answered. He finally realized his job was to sell stuff and I was a real live customer, so he took off in search of the boss.

“We’ll take 30 off,” Junior said when he returned.

“Is that percent, or dollars?” I asked.

He smiled. “Dollars.” It was still a hell of a deal, so I pulled the trigger. Today if I wanted to sell this gun I could probably get $1500 for it. But I don’t want to sell it, and I never will.

I don’t shoot my Turnbull 1917 all that often; my preference is the Model 625 described below. The 1917 groups well, but its small checkered grips are punishing. This is another cool gun. I’ve never seen another one on the range.

Smith’s Performance Center Model 625

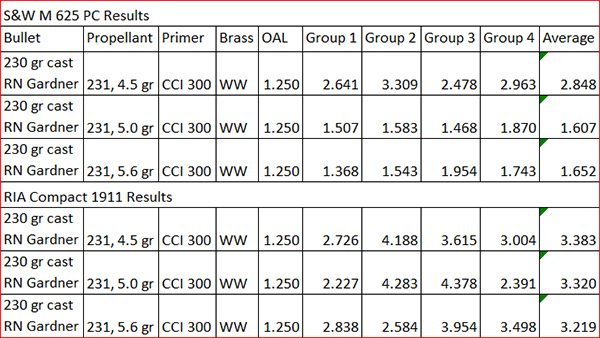

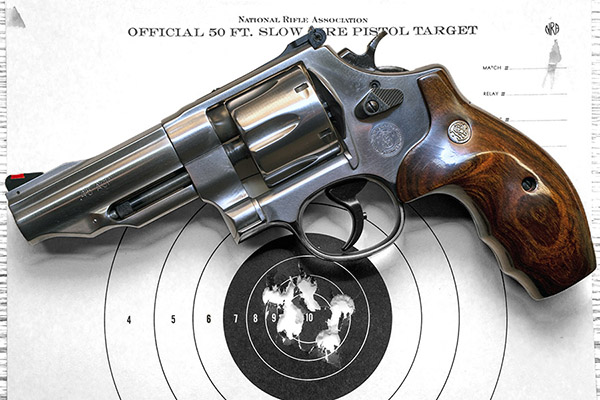

The Performance Center is Smith’s marketing shtick for guns that have been slicked up a bit, which is Smith and Wesson’s way of saying they build Performance Center guns with the attention to detail that used to be standard on all Smith and Wessons. This one has a good trigger, a different barrel contour, blended edges on the front of the cylinder, and probably a few other niceties I can’t remember right now.

This revolver originally had clown-like, awkward, red-white-and-blue grips. I quickly swapped the goofy factory grips for what were advertised as rosewood grips from a third-party vendor (they weren’t rosewood at all; they were instead fabricated of cheap laminated and dyed wood, as I found out when I refinished them). But my custom grips fit my hands much better, and this is an extremely accurate revolver. I also installed a red ramp front sight and a white outline rear site. The white outline rear sight Smith sells today has barely-visible gray lines and the red is not as bright as it used to be, but they are better than the gold dot front sight and plain black rear sight that came on the gun (I don’t like gold dot front sights).

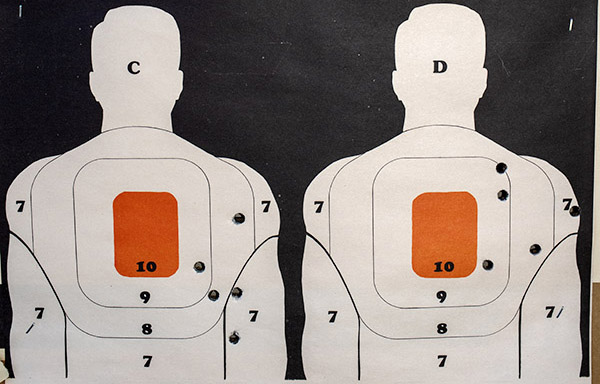

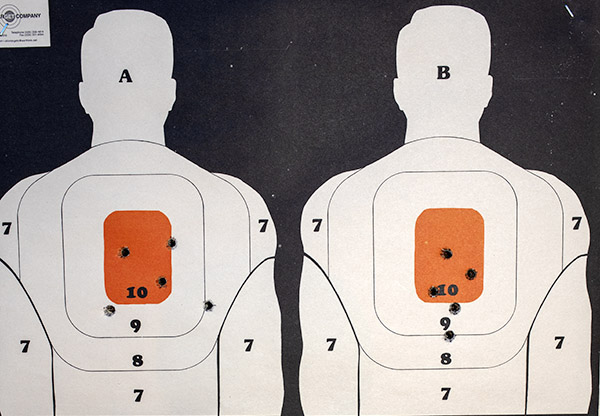

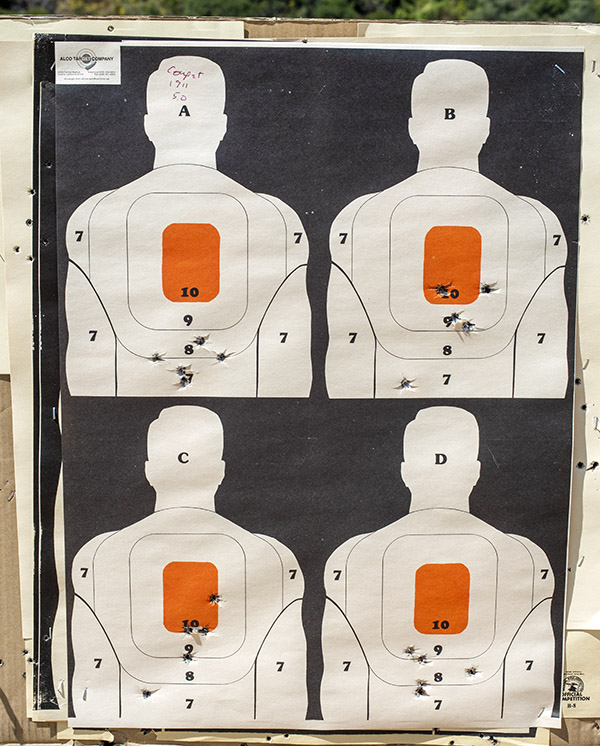

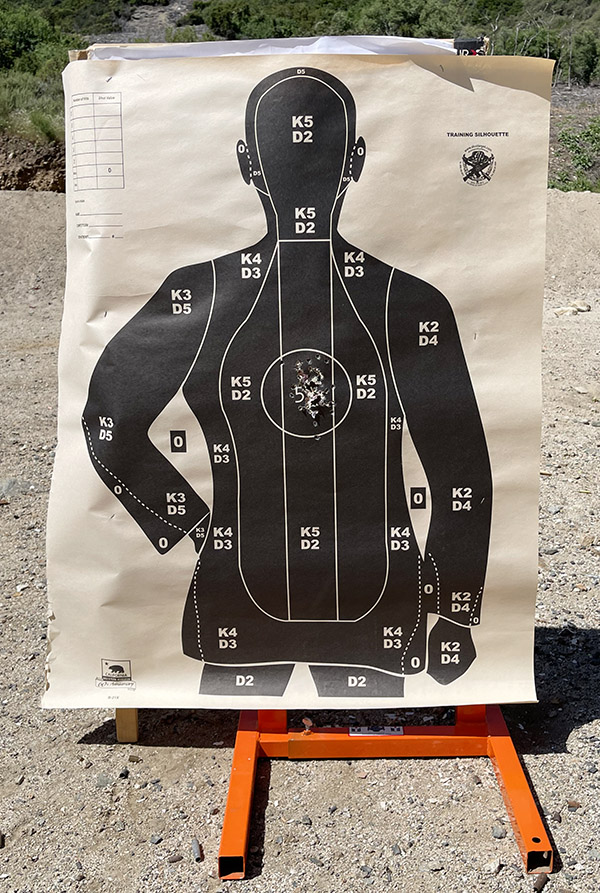

My usual accuracy load for the 625 is a cast 200-grain semiwadcutter bullet (sized to .452 inches) over 4.2 grains of Bullseye. Another load that works well is the same bullet with 6.0 grains of Unique (it’s the load I used on the target above).

After reading about the above Smith and Wesson .45 ACP revolvers, you might have two questions:

-

-

- Which is my favorite?

- Which do I prefer: A .45 ACP revolver or a 1911?

-

The answer to both questions is: Yes.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

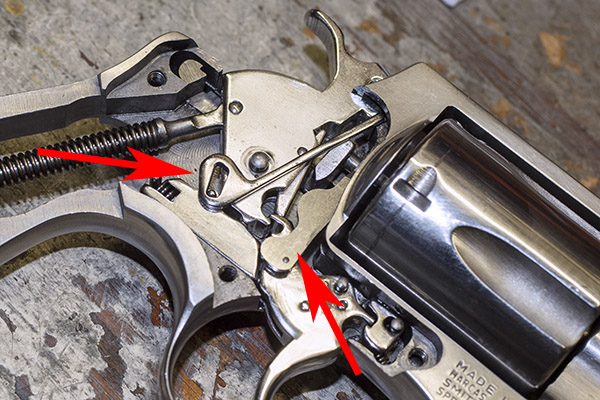

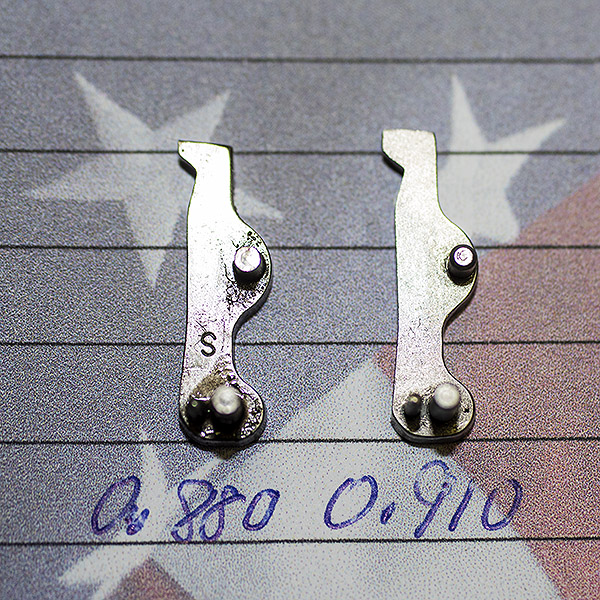

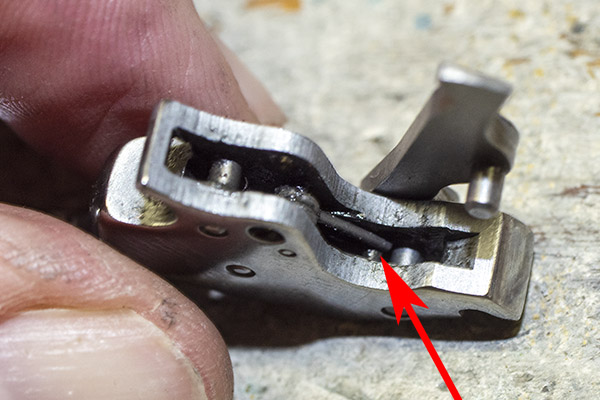

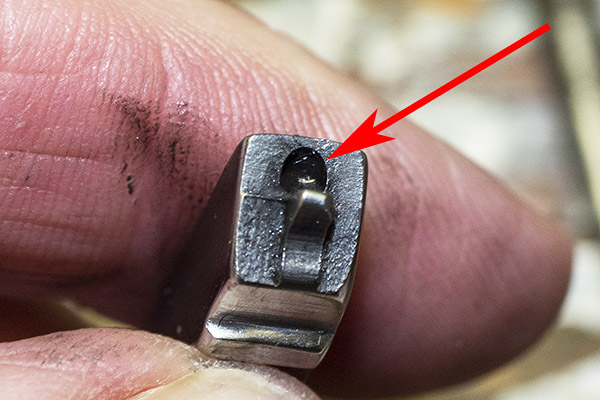

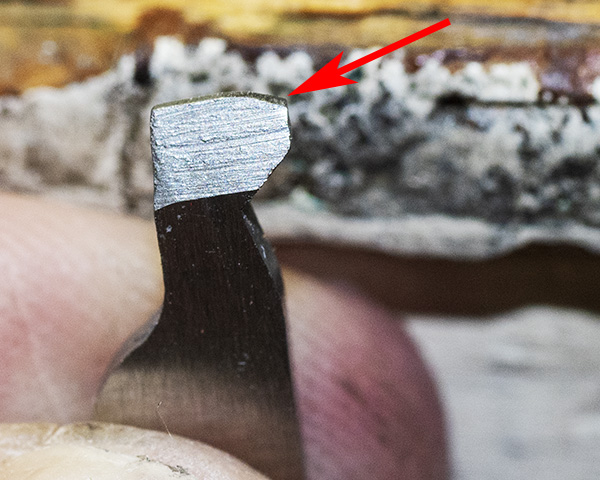

You can see there’s a big difference in length between the old and the new hands. I bought my new hand from MidwayUSA.com. It was about $25.

You can see there’s a big difference in length between the old and the new hands. I bought my new hand from MidwayUSA.com. It was about $25.

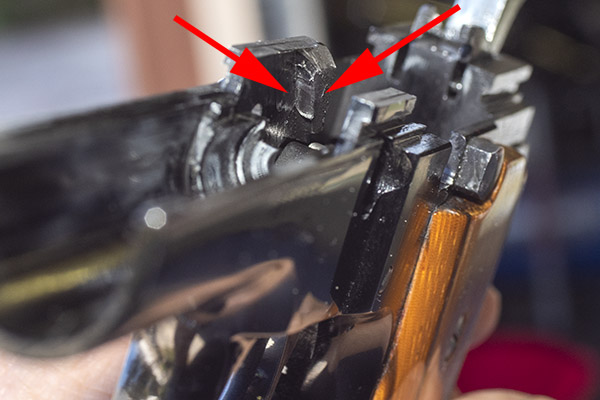

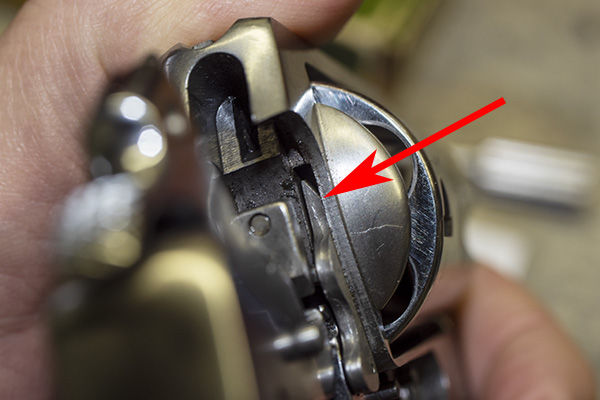

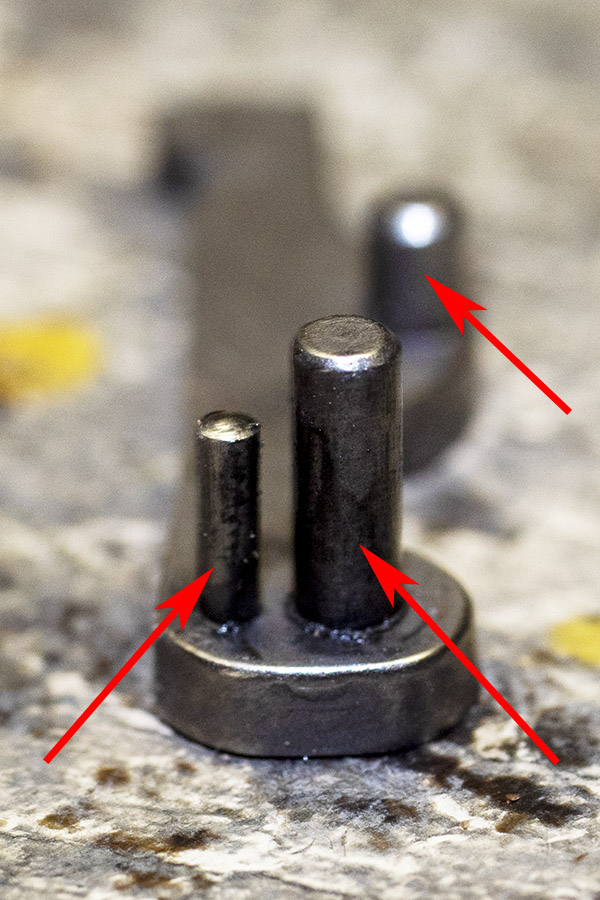

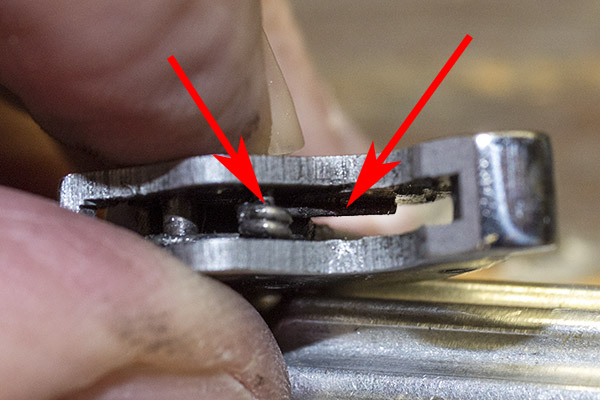

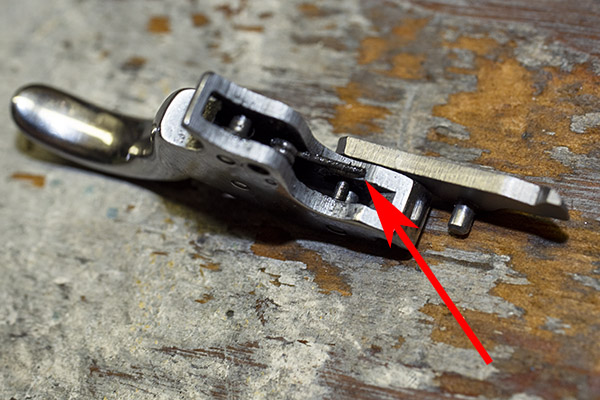

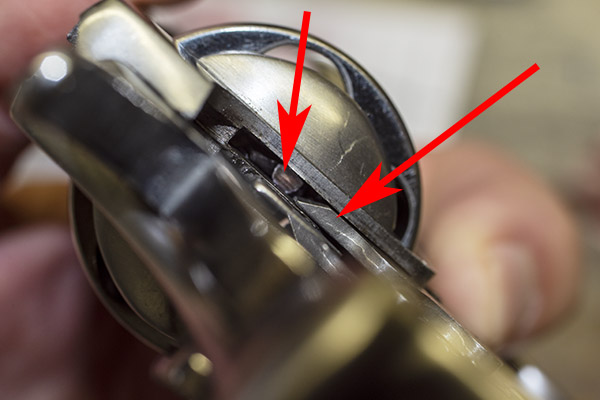

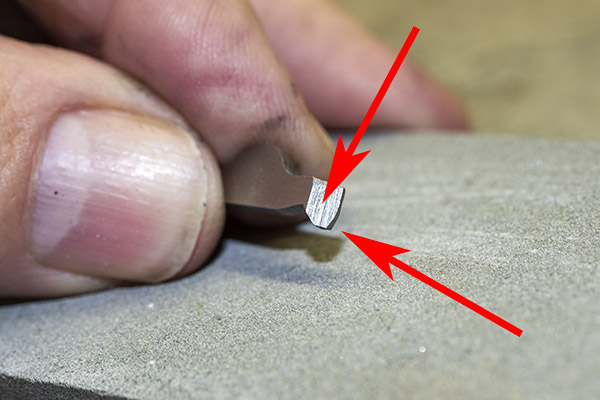

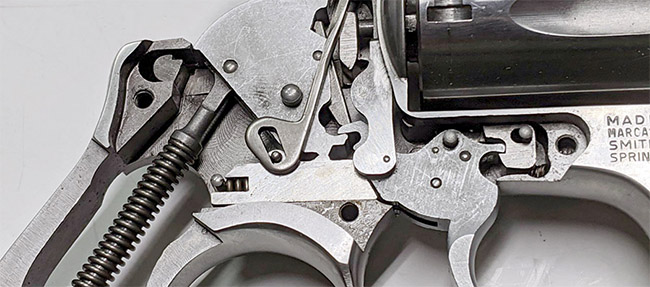

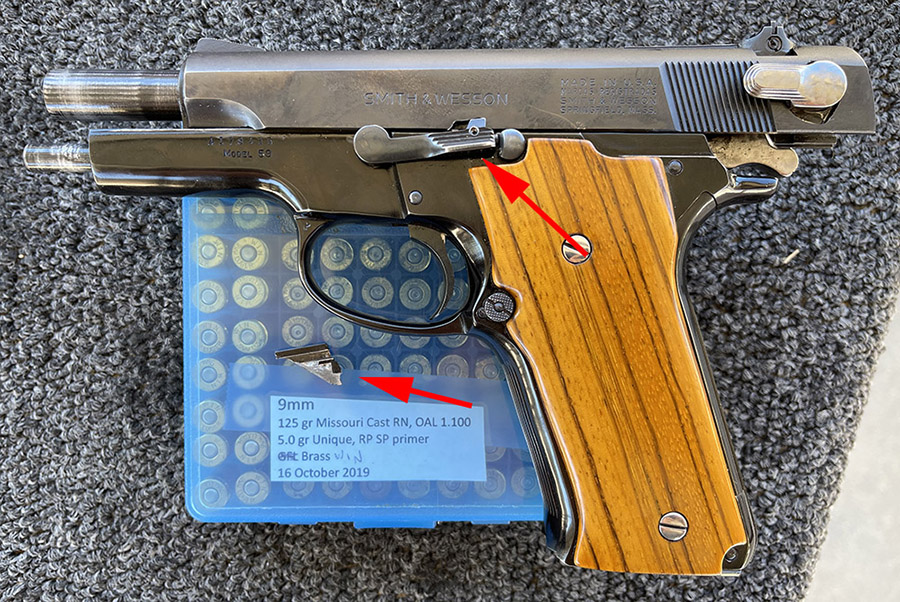

The arrows in the next pic point to the matching right side of the Model 59 frame. Note the worn area. It’s where the barrel ramp contacts the frame ramp when the gun recoils. That ramp (along with the mating ramp on the barrel) drops the barrel slightly to disengage it from the slide when the slide moves to the rear. You can see this area took a beating over the last 50 years. The photo shows the opposite side of the frame, where it didn’t break.

The arrows in the next pic point to the matching right side of the Model 59 frame. Note the worn area. It’s where the barrel ramp contacts the frame ramp when the gun recoils. That ramp (along with the mating ramp on the barrel) drops the barrel slightly to disengage it from the slide when the slide moves to the rear. You can see this area took a beating over the last 50 years. The photo shows the opposite side of the frame, where it didn’t break.