This blog is longer than I intended it to be. I thought I would just do a quick bit about a new set of Lee reloading dies I recently purchased, but as I got into it, I learned more about my Colt Python, crimping with a bullet seating die versus a dedicated factory crimp die, and well, the thing just grew. Mea culpa; you can leave early if you want to. Because this is a longer-than usual post, I thought I’d provide the bottom line up front: The Lee factory crimp die is a good thing. It works. It holds bullets in place better, it improves chambering, and it improves accuracy.

Now, the rest of the story.

For the last umpteen years when loading .38 Special or .357 Magnum ammo I have been using a kluged-up three die set (a carbide resizer/decapper from Dillon, an expander die from Lee, and a bullet seating and roll crimping die from Lee). You can use the same dies for both .38 Special and .357 Magnum; the only difference between the two cartridges is the length of the cartridge case. They use the same diameter bullets (even though it’s called a .38 Special, the bullet diameter of a .38 is actually .357 to .358 inches, just like the .357 Magnum).

Reloading Gear

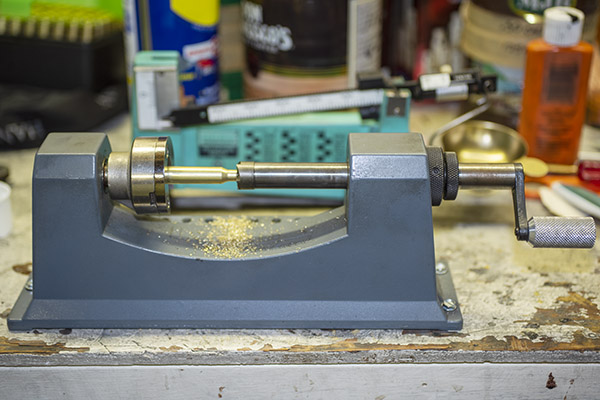

I’ve had a few .38/.357 die sets over the years, selling them when convenient as I bought or inherited other equipment. As featured here on the ExNotes blog, I have a 50-year-old Star reloader I use for .38 Special wadcutter ammo (I’ll give you a link for the Star story at the end of this blog). The Star is set up to meter 2.7 grains of Bullseye propellant (that’s a 148-grain wadcutter target load) and it works fabulously well, so it’s a dedicated setup. For all other .38 Special and for .357 Magnum reloading, I load with my RCBS Rockchucker single-stage press. I’ve been using it for 50 years.

Bullet Seating and Crimping

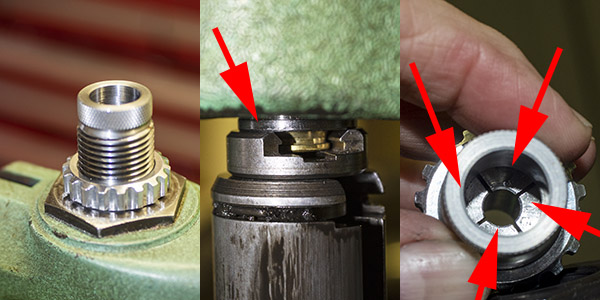

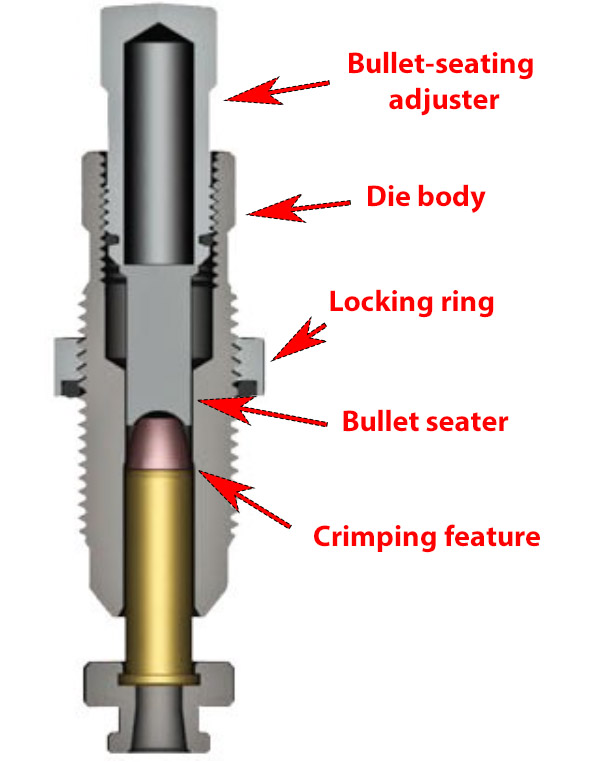

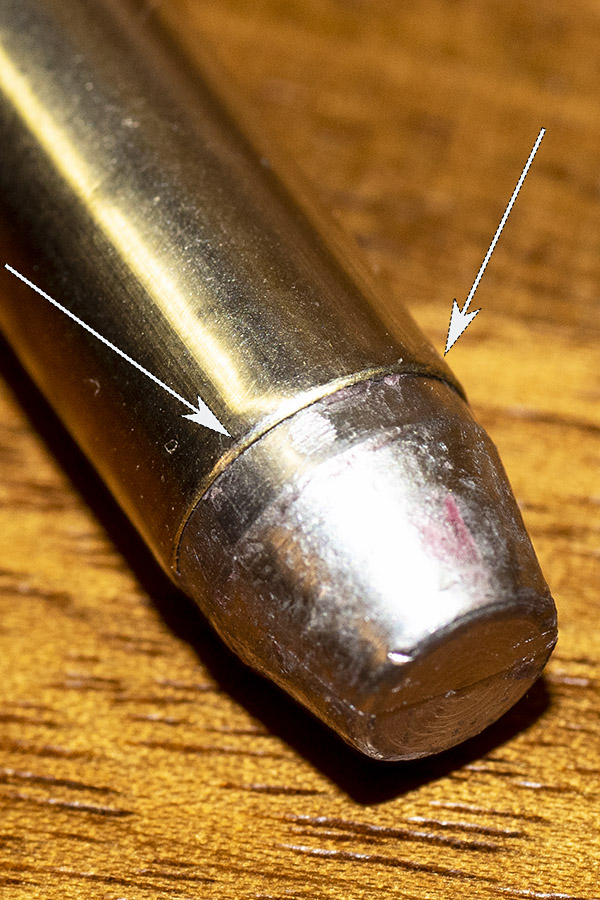

For many years, I seated and crimped my bullets with a simple seating and crimping die. It’s what you see in the illustration below.

I use this die in two steps. First, I screw the bullet seating adjuster deep into the die and seat the bullet to the correct cartridge overall length without crimping the bullet in place. After seating all the bullets, I then back off on the bullet seating adjuster so that it no longer contacts the bullet, and then I screw the die body deeper into the press. The die body has a roll crimping feature that then roll forms a crimp around the case mouth to lock the bullet to the cartridge case.

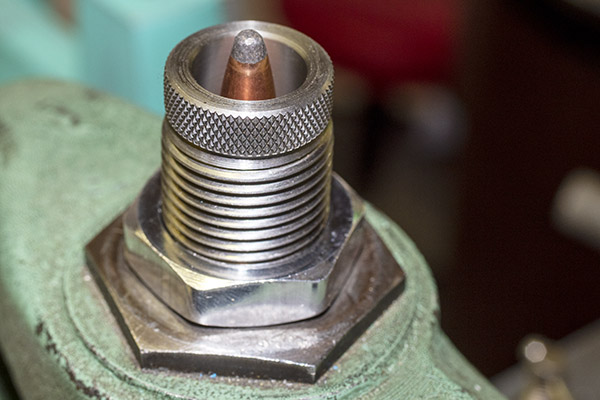

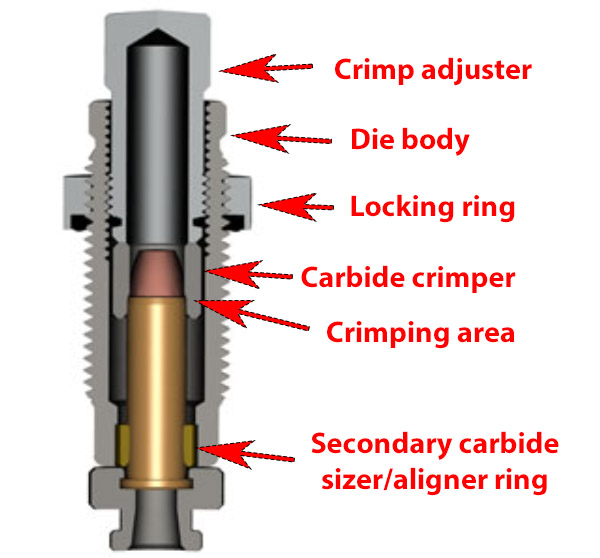

Lee has an alternative approach for bullet crimping they call the factory crimp die. As a first step, you seat the bullet to the desired depth in the case using the die shown above. After seating all the bullets, you then remove the bullet seating and crimping die from the press and then use the fourth die (the factory crimp die). Here’s what the factory crimp die looks like:

The fourth die, the factory crimp die, does not seat the bullet. Its only function is to apply the crimp, and it does this very well. The idea is that the die is screwed all the way into the press such that it contacts the shellhoder, and then the amount of crimp is set up with the crimp adjuster, which screws into the die body. This die applies a roll crimp on a revolver cartridge (the same kind of crimp as the bullet seating and crimping die described above), but it does so in a much better-controlled manner. The factory crimp die also has a secondary carbide sizer/aligning ring at its lower end, which aligns the cartridge as it enters the case, and holds the cartridge outside diameter to specification values as the cartridge enters and then exits the die. It works fabulously well, and Lee states that this die makes it impossible to buckle a case.

I had .357 Magnum ammo I had previously loaded using the bullet seating and crimping die only (not the Lee factory crimp die), and it chambered with no problem in my Ruger Blackhawk. The Colt Python has a tighter chamber, though, and several of these older reloads would not chamber in the Python. A quick trip through the Lee factory crimp die cleaned up the outside diameters and the rounds chambered easily.

Lee’s Deluxe 4-Die Set

I recently ordered a new Ruger Blackhawk, and I’ve written many times about my Colt Python. With my new .357 Magnum Blackhawk in its 10-day cooling off period, I thought I would get a new set of dies. I like Lee (they give you a shellholder, they are inexpensive, and they do a good job). I had bent the decapping pin on the Dillon sizing die in my mixed set of dies shown above (a primer wouldn’t come out and I forced it). I was able to bend the pin straight, but I figured a man of my stature ought to have a set of grownup new dies. Then I got an email from MidwayUSA showing the Lee 4-die set on sale for $53 and they had free shipping on orders over $49. The Lee Deluxe set includes the factory crimp die. All the planets were in alignment (enter order, buy now…you know the drill). The dies were at my front door a few days later.

The new dies looked great, and I was eager to put them to work.

Bullet Pull and Cylinder Rotation

On revolvers with significant recoil, bullets can back out of the cartridge case when other rounds in the cylinder are fired. This can allow bullets on unfired cartridges to protrude beyond the cylinder face and interfere with cylinder rotation. We prevent this by controlling the reloaded cartridges’ overall length and by crimping. In firing my new Colt Python with ammo I had loaded for an earlier Ruger Blackhawk, even though the bullets were crimped I experienced bullet pull beyond the front of the cylinder. When this occurred, the cylinder would not rotate. These same rounds had worked in a Ruger Blackhawk.

In analyzing the cylinder rotation issue on my new Python, I found several things:

-

-

- The bullets were not seated deep enough (the cartridge overall length exceeded the maximum spec of 1.590 inches), even though the bullets were crimped in their crimping groove.

- The crimp wasn’t strong enough to hold the bullets in place. Under recoil from other cartridges, the bullets were backing out.

- The Python cylinder is slightly shorter than the Ruger Blackhawk cylinder. I probably had the same bullet pull occurring on the Blackhawk, but the Blackhawk’s longer cylinder masked it. They might have been backing out on the Ruger and I didn’t know it.

-

Cartridge Overall Length

Let’s dive into the numbers. The reloading manuals show the .357 Magnum maximum cartridge overall length (COAL) to be 1.590 inches. With my cast bullets crimped in their crimping groove, the overall length was running from 1.607 to 1.615 inches. That put them about even with the front of the Python cylinder. If any bullet pull occurred under recoil, the front of the bullet would hit the rear of the forcing cone and the cylinder wouldn’t rotate. That’s what I experienced with my Python.

The Ruger New Model .357 Blackhawk has a longer cylinder than the Python. The Ruger cylinder is 1.640 inches long. The Internet says the Python cylinder length is 1.552 inches; mine measures 1.553 (which is close enough). Right away, the astute ExNotes blog reader will recognize that the Colt’s cylinder (at 1.552 inches) appears to be shorter than the specification .357 Magnum cartridge maximum overall length (1.590 inches), but it is not. When loaded in the cylinder the cartridge is held rearward by its rim, which sits flush against the back end of the cylinder.

The .357 Magnum cartridge rim backs the cartridge up 0.060 inches (the rim thickness), which would put the leading edge of the bullet in a cartridge loaded to an overall length of 1.590 inches about 0.023 inches inside the front edge of the cylinder (if I’ve done the math correctly). And I think I have, because when you look at cartridges in the Python cylinder, they are pretty close to the edge of those big .357 cylinder holes. 0.023 inches. Twenty-three thousandths of an inch. That’s not much to play with.

Bullet Design and Crimp Location

I examined the bullets I was using. I had crimped my cast bullets in the crimping groove, and I could see that the crimping groove put the bullet face very close to the forward end of the Python’s cylinder. I couldn’t seat the cast bullets any deeper and still crimp in their crimping groove. Hornady’s jacketed 158-grain bullets are no problem; their crimping groove is a lot higher on the bullet.

Test Objectives

I wanted to test bullets seated and crimped using both approaches (i.e., the bullet seating and crimping die, versus seating with the bullet seating die and crimping separately with the Lee factory crimp die). My testing would evaluate the following:

-

-

- Bullet movement under recoil.

- Accuracy.

- Ease of chambering.

- The ability to get a good crimp in locations other than the crimping groove.

-

That last one is important, because as I learned with my Python, crimping some cast bullet configurations in the crimping groove makes the cartridge too long.

Test Ammo

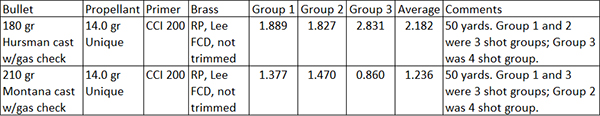

I loaded three test lots. The first was with 15.7 grains of Winchester 296 powder, Winchester small pistol magnum primers, and Hornady’s 158-grain jacketed hollow point bullets. That was my accuracy load when shooting metallic silhouette a few decades ago, so I know it works well. I loaded half with the bullets crimped using the old Lee bullet seating and crimping die (not the factory crimp die), and the other half with the bullets crimped with my new Lee factory crimp die (after seating them with the bullet seating die).

The second lot of ammo was a group I had loaded several years ago. This ammo had 158-grain cast semi-wadcutter bullets crimped in the crimping groove, 7.0 grains of Unique, and Winchester small pistol primers. That load (7.0 grains of Unique and a 158-grain cast bullet) has been accurate in every .357 revolver I’ve ever shot. I loaded this ammo with the bullet seating and crimping die (not the Lee factory crimp die). I’d shot tons of this load in an older Ruger Blackhawk, but I had not tried it yet in my Python.

The third ammo lot was similar to the one above (same bullet weight and powder), but I used the cast truncated flat point bullet and I crimped above the bullet’s crimping groove using the Lee factory crimp die. I wanted to get the bullet further back from the cylinder face to prevent cylinder rotation inteference if the bullets pulled under recoil. My concern was that I would be crimping above the crimping groove, on the bullet’s main diameter, and I didn’t know if the crimp would hold the bullet in place.

When loading with my new Lee Deluxe 4-die set, I noticed immediately that the resizing operation was much easier. The same was true for the expander die step. Maybe the older dies I had been using were just dirty, but I sure like do the feel of these Lee Deluxe dies.

Some of you may wonder: Why not just trim the brass shorter to a below-spec length? That would move the bullet back, and if I trimmed it short enough it would allow me to crimp these cast bullets in their crimping groove and not risk any cylinder rotation interference. Yeah, I could have done that, but when I trim brass I like to trim it to specification, not something below spec. And I don’t want to have to segregate brass based on trimmed length tied to specific firearms.

Test Results: Bullet Movement

The first test objective was to determine how much bullet movement occurs during recoil using the two different crimping approaches. Here’s how I tested:

-

-

- I loaded 5 rounds in the revolver.

- I took a 6th round and recorded its cartridge overall length, and then I loaded it.

- I fired the first five cartridges.

- I removed the unfired 6th round and measured the overall length again.

-

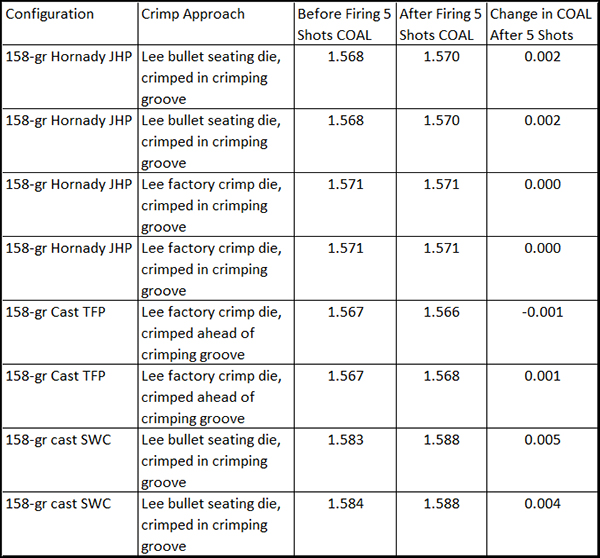

Here’s what I found in assessing the two crimping approaches’ ability to prevent bullet pull:

The results surprised me. The Lee factory crimp die, even when done on the main diameter of the bullet (not in the crimping groove) does a better job holding the bullet in place than does crimping with the bullet seating die. In each test in which the bullets were crimped with the bullet seating die, they experienced recoil-induced bullet movement. That one entry where the overall length decreased by 0.001 inch is probably measurement error on my part.

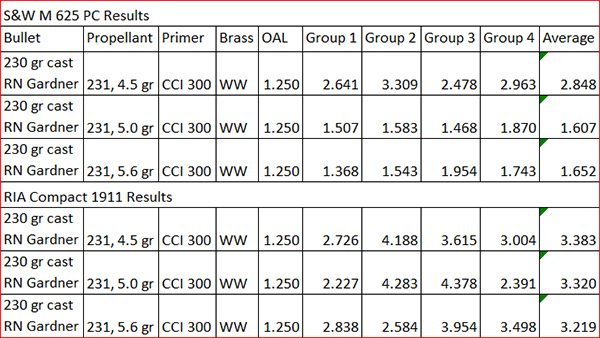

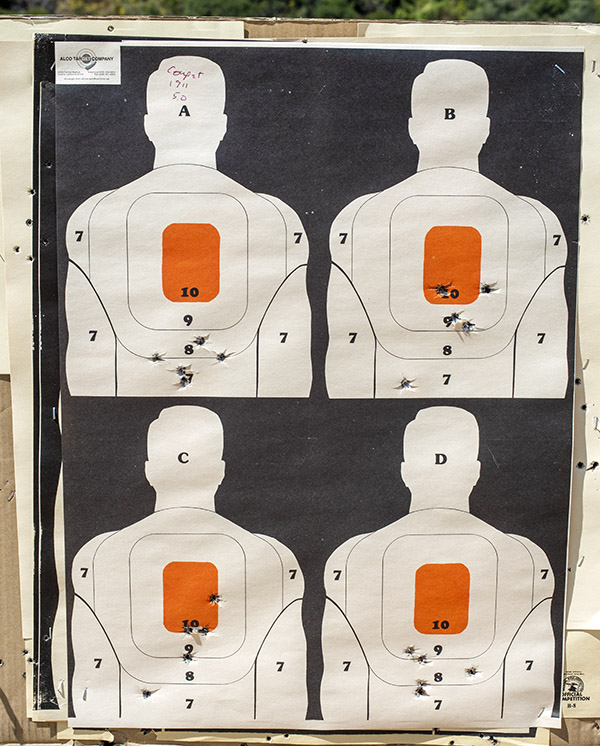

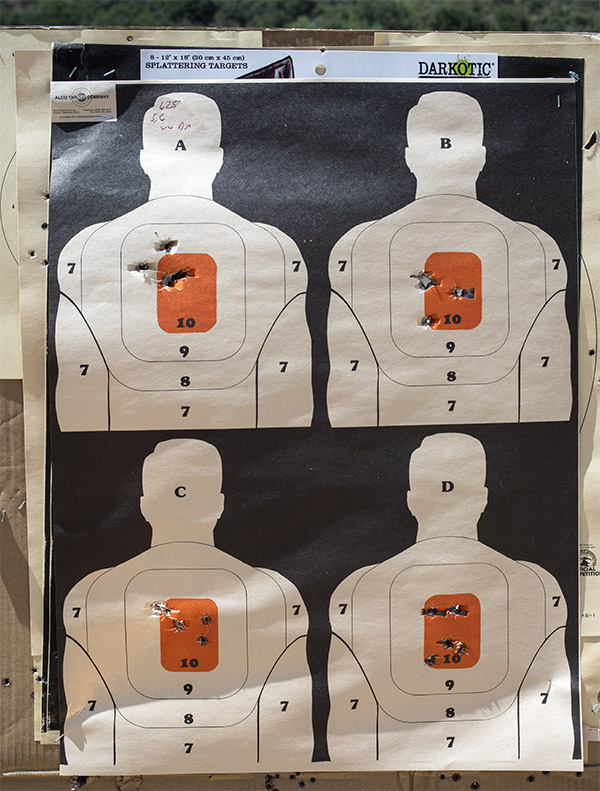

Test Results: Accuracy

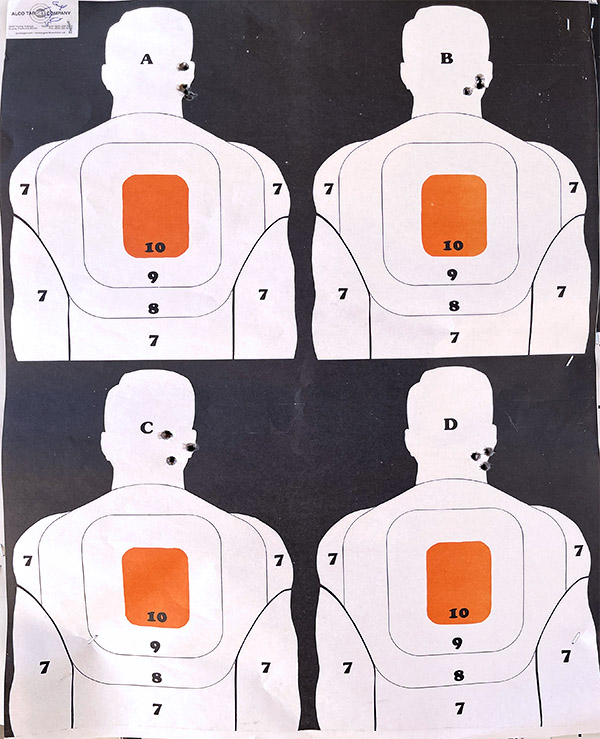

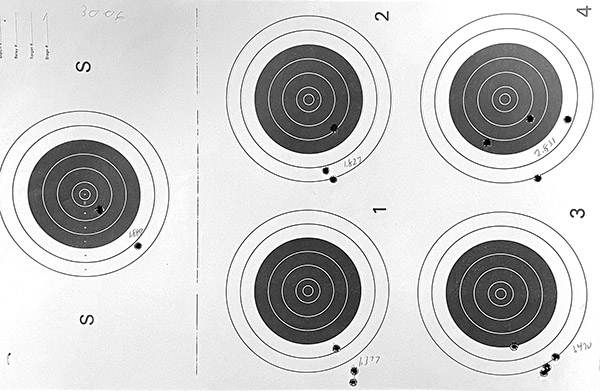

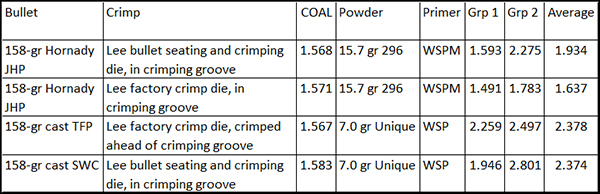

This testing was straightforward. I fired a series of 5-round groups at 50 feet to assess any differences in accuracy.

Here’s what I see in the above results:

-

-

- With the Hornady jacketed hollow point points, using the Lee factory crimp die resulted in an improvement in accuracy (the group average was 1.637 inches compared to 1.934 inches).

- The Hornady jacketed hollow point bullets were more accurate than the cast bullets. That was an expected result.

- With the cast bullets, there isn’t much of an accuracy difference between using the bullet seating and crimping die versus using the bullet seating die and then the Lee factory crimp die.

- With the cast bullets, there wasn’t much of an accuracy difference between the truncated flat point bullets and the semi-wadcutter bullets.

-

I wasn’t having my best range day ever (I had a bad cold when I fired these groups). But I think I did well enough to support the above conclusions.

Test Results: Ease of Chambering

I already mentioned this. Lee claims that the factory crimp die will not buckle or distort the case during crimping. My results confirm this. A few rounds that had been crimped with the bullet seating die would not chamber in the Python; after running these through the Lee factory crimp die, they chambered easily. The Lee factory crimp die does a better job for ease of chambering.

Test Results: Crimping Without a Crimp Groove

This is really a subset of the first test objective, in which we evaluated the ability of the Lee factory crimp die to hold bullets in place under recoil. Here, the focus is more specific: I crimped on the bullet’s main diameter, not in the crimping groove, and I wanted to determine if the Lee factory crimp die would secure the bullet in place. As you can see from the data above, it did. When I crimped the cast truncated flat point bullets forward of the crimping groove, they did not move under recoil. The Lee factory crimp die did this well, and it did so without buckling the cartridge case.

The Bottom Line

The Lee factory crimp die is a good thing. It holds bullets in place better, it improves chambering, and with jacketed bullets, it improves accuracy.

If you want to buy a set a Lee dies, or the Lee factory crimp die, or any Lee reloading equipment, Amazon is a good place to shop. Midway is, too. But I usually go to Amazon first.

If you have comments, be sure to let us know in the comments section below. We enjoy hearing from you.

The Star reloader resurrection story is here.

Hit those popup ads!

Want to read our handgun ammo reloading tutorial? It’s right here.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

More reloading and gun articles are on our Tales of the Gun page.

For more info on Lee Precision reloading equipment, click on the image below: