This is an interesting story and it’s one of the very few times in my life I was hosed on a firearm purchase. The rifle is a 1903 Springfield I bought a few years ago and didn’t shoot much. The times I shot it previously I had experimented with cast bullets and it shot okay, but not great. Then I tried it with jacketed bullets (loads at much higher pressures), and what do you know, I had a headspace issue. I could see it in the primers that had partially backed out of the brass after firing, and on one round, I split a case circumferentially just ahead of the base (indicating with near certainty an excess head space issue). I borrowed good buddy Greg’s 30 06 head space gages, and the bolt closed on both the no go and the field service gages. That’s a no no.

My first thought was to have the existing barrel set back and rechambered, but that didn’t work. The 1903 Springfield has a barrel collar that holds a very sophisticated rear sight and positions the upper handguard. When we set the barrel back, the rear sight integrity was greatly weakened and the front handguard had excess play. Nope, I needed a new barrel.

I checked around and came to the conclusion that the best place to get this kind of work done is the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP) Custom Gunshop. This is a quasi-government arsenal and these folks are the experts. I priced having a new barrel and rear sight collar installed on my 1903, cutting a new 30 06 chamber with the correct headspace, and having the entire gun re-Parkerized. The work was surprisingly reasonable. I had to wait my turn in line, but that’s okay. I had other guns I could shoot.

When the rifle was returned to me, it was stunning. It literally looked like a brand new 1903. A quick trip to the range followed, and I tried some jacketed bullet factory level reloads. I loaded and fed from the magazine, as the 1903 is a controlled round feed and it’s best in these guns to let the cartridge rim ride up and find its position behind the extractor.

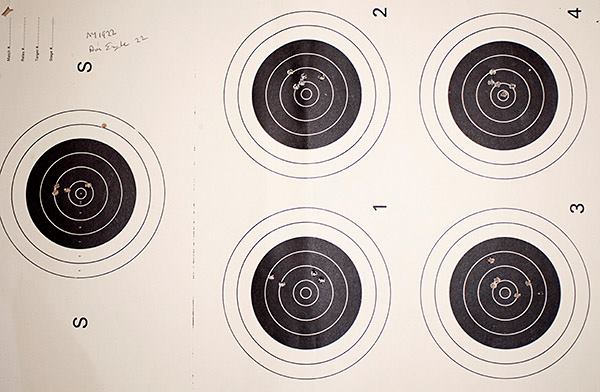

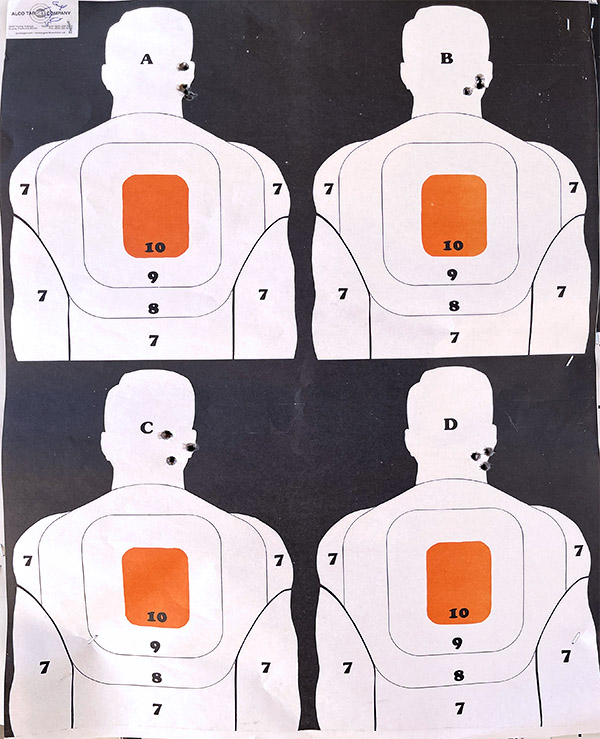

I shot a few targets with copper jacketed bullets and found that the rifle shot about a 8 inches high and slightly to the right. The rear sight would take care of the right bias, and I figured the high impacts were okay. Some military rifles of this era are designed with a 300-yard battlesight zero, which means they shoot to point of aim at 300 yards at the lowest sight setting (everything in between is high, with the idea being that if you hold center-of-mass on a human size target, you’ll have a hit out to 400 or 500 yards).

I could buy a taller front sight blade to lower the point of impact, but that wasn’t the way I wanted to go. Nope, my plan was to shoot cast bullets in this rifle. My guess was that if the rifle shot 8 inches high at 50 yards with jacketed bullets, cast bullets would be right where I wanted them to be.

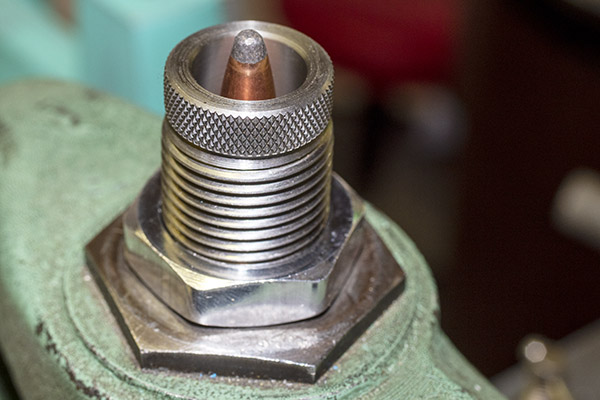

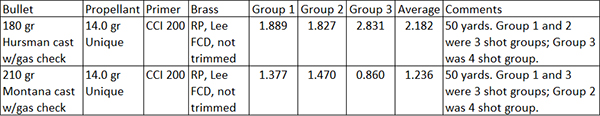

Loading my first batch of 1903 cast bullet test ammo was easy. Years ago I was on a reloading tear, and I had loaded a bunch of plated 110-grain round nose bullets with 14.0 grains of Unique. I knew those loads were terrible in other 30 06 rifles (the lead under the copper plating is dead soft and it tears off, resulting in terrible accuracy). Hey, no problem. I pulled the plated bullets, left the 14.0 grains of Unique in the cartridges, flared the case mouths, and seated different cast bullets. One was the 180-grain cast Hursman bullets with gas checks (these worked well in the .300 Weatherby), the other was the 210-grain Montana bullets I picked up from good buddy Paul (these are also gas checked bullets). After seating the cast bullets, I crimped the brass with my Lee factory crimp die.

I only loaded 20 rounds (10 each with the two different cast bullets), as this was to be a “quick look” evaluation.

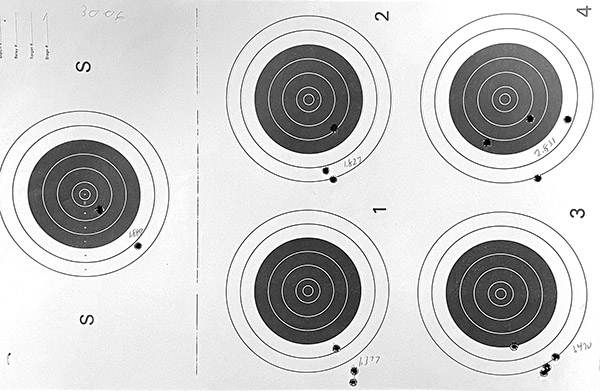

Both loads shot reasonably well. I’m not going into the upholstery business with either of these loads (they are not tack drivers), but they are good enough. I was particularly pleased with the 210-grain Montana bullets. The Hursman bullets had proved to be the preferred load in the .300 Weatherby; the Springfield showed a decided preference for the Montana bullets.

I shot at 50 yards with both loads; future testing will be with the Montana bullet at 100 yards.

Unique is not the best powder out there for loading cast bullets in rifle cartridges. In the past, I’ve shot much better groups in other rifles with IMR 4227, 5744, SR 4759, and Trail Boss. Those evaluations in the 1903 are coming up. For now, I know I’ve got a good load with Unique and the Montana bullets.

One of the big takeaways for me in this adventure is that when you buy a milsurp rifle, always check the headspace to make sure that it is within specification. It’s pretty common for these rifles to have gone through arsenal rebuilds and to have been cobbled together from parts bins, and when that occurs, if the chamber isn’t matched to the bolt you can have an excess headspace problem. That’s a bad situation, as it can be dangerous to the shooter and anyone nearby.

You can find headspace gages on Amazon and elsewhere. If you’re going to buy a military surplus rifle, checking the headspace should be part of the drill.

Why you should click on those popup ads!

More Tales of the Gun!

The ultimate milsurp gun? Hey, check this out: