By Joe Berk

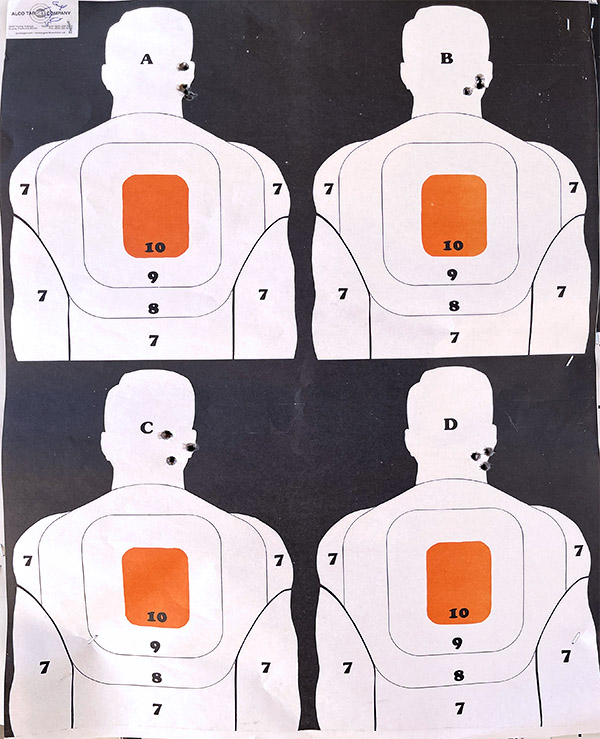

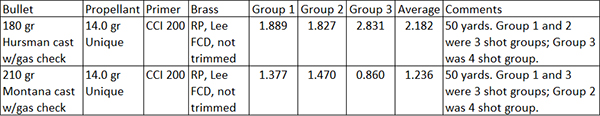

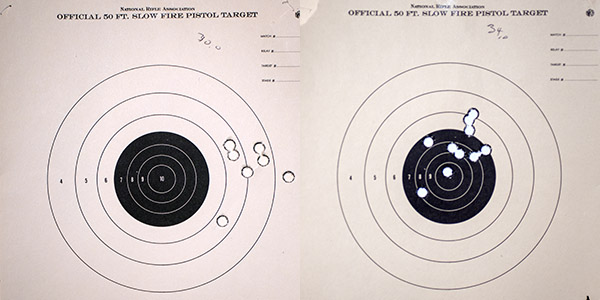

You’ll recall a recent blog where I waxed eloquent about Eleanor, my Ruger RSM .416 Rigby rifle. In that blog, I talked about reduced loads using 350-grain cast Montana bullets and 5744 and Trail Boss propellant. It was fun…the Trail Boss loads had milder recoil and “good enough” (but not stellar) accuracy. Take a look at these 50-yard targets:

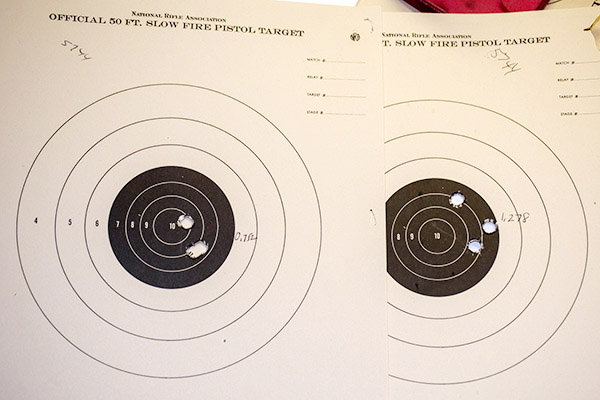

The above target on the left was with 30.0 grains of Trail Boss; the one on the right was with 34.0 grains of Trail Boss. I could feel a tiny bit more recoil with the 34.0-grain load, but both were light loads with modest recoil. Weirdly, the point of impact shifted sharply to the right with the lighter load, but it moved back to the center with the 34.0-grain load (and it was slightly higher). The Trail Boss loads shot okay, but they weren’t running in the same league as the load I had shot the prior week with 5744 propellant and the same Montana Bullet Works 350-grain bullet, as you can see from the 50-yard targets below.

I could see what I was getting with the Trail Boss and I could see that it wasn’t grouping nearly as well as the 5744 loads at 50 yards, so that stopped my testing with Trail Boss (that, and the fact that I had used up all my Trail Boss cartridges).

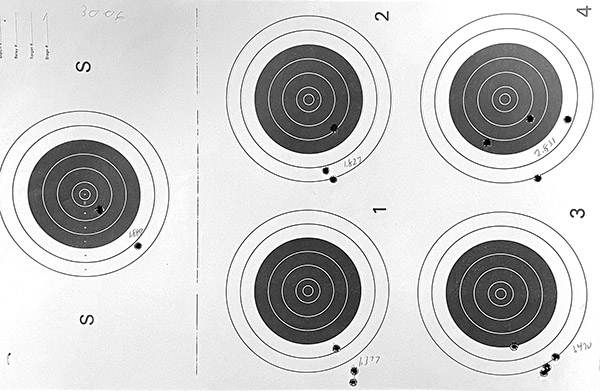

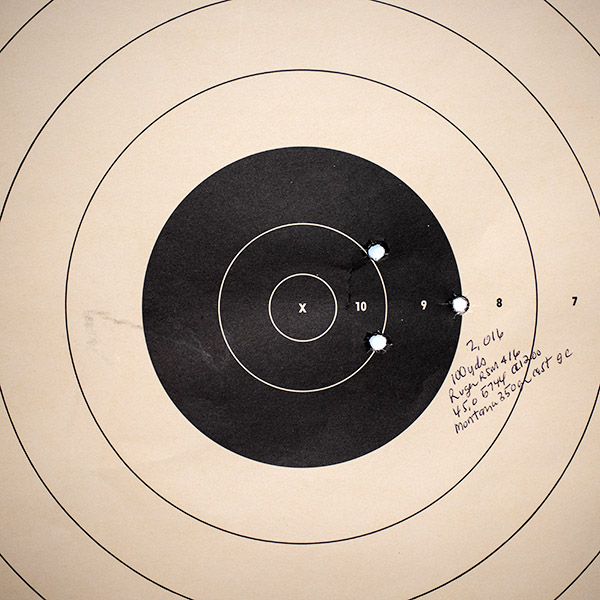

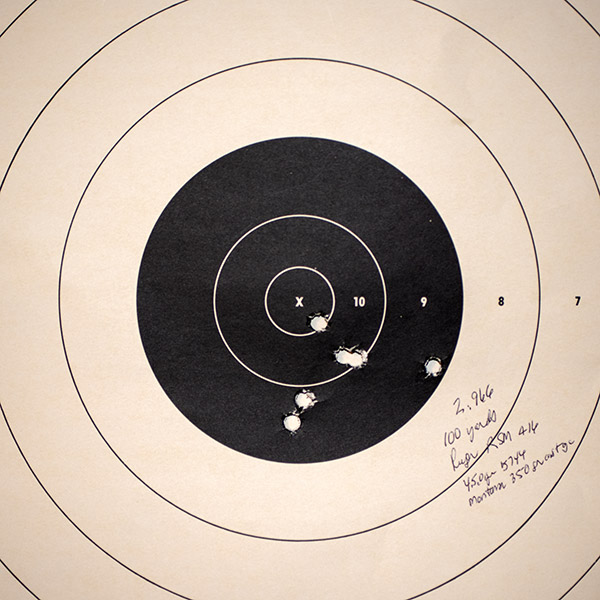

I was curious: How would Eleanor do at 100 yards? I still had some of the 5744 loads left, so I posted a couple of 100-yard targets and let Eleanor have her way. I first fired a 3-shot group and after looking through my spotting scope, I was surprised to see how well they grouped.

I thought maybe that target was a random success, and I didn’t want to ruin it by throwing more shots at it. So I fired another 3-shot group at the second target, and then another three at that same target. That’s the one you see below.

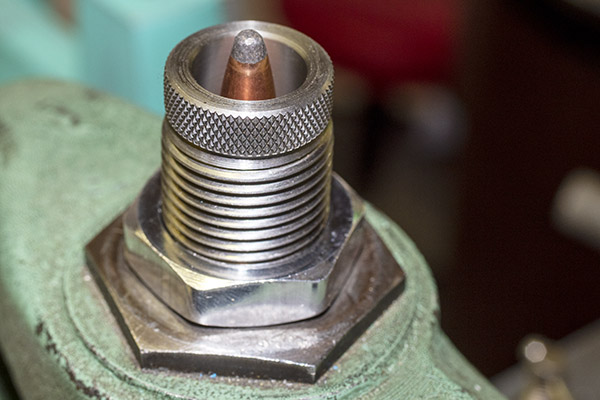

Before all you keyboard commandos start telling me that these results are nothing special, allow me to point out that these are 100-yard groups using open sights on an elephant rifle. I’m calling it good to go. Like I said earlier, when the elephants become an invasive species here in So Cal, I’m ready. The load is 45.0 grains of 5744 (it’s the load the Lyman Cast Bullet Handbook specified as the accuracy load, and they were right), the 350-grain Montana Bullet Works .416 bullet sized to .417 and crimped in the cannelure, Hornady brass, and a CCI-200 primer. I didn’t weigh each charge; I just adjusted my RCBS powder dispenser

and cranked them out. If you were wondering, I use Lyman dies

for this cartridge.

A bit more about Eleanor: The rifle is a Ruger 77 that the good folks from New Hampshire call an Express or RSM model (I think RSM stood for Ruger Safari Magnum). They made them in 375 H&H, 416 Rigby, and 458 Lott (kind of a magnum .458 Magnum). Ruger also made a similar one in a few of the standard calibers (7mm Mag, 30 06, and 300 Win Mag, and maybe one or two others). These rifles were a bit pricey when Ruger sold them in the late 1990s/early 2000s, but evidently not pricey enough. They were too expensive to manufacture, so Ruger stopped making them. When you see these rifles come up for sale today (which doesn’t happen very often), they command a premium. I wish I had bought one in 30 06 when they were first offered; to me, that would be the perfect rifle.

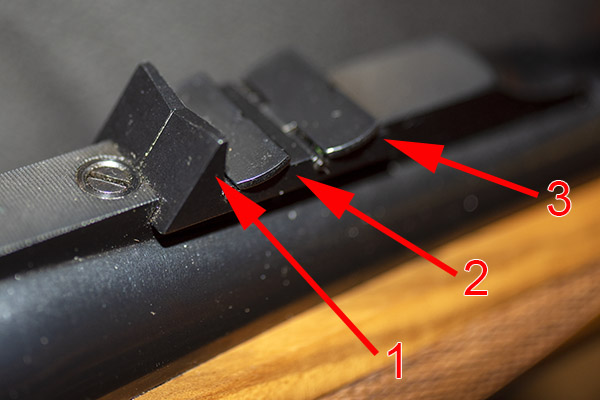

The rear sight on a Ruger RSM rifle is of the African “Express” style. The elevation adjustment consists of a fixed and two flip-up blades, and they all have a very shallow V. I guess the idea of that shallow V is that it lets you see more in case an elephant is charging. The sight has two flip up blades behind the fixed blade; as range increases, you flip up the second blade, and if it is an even longer shot, you go for the third blade. I got lucky, for me, the fixed rear sight blade is perfect with this load. I made a minor adjustment for windage, and the elevation is spot on with a 6:00 hold at both 50 yards and 100 yards.

Incidentally, that rib the rear sight sits on? It’s not a separate piece. It and the barrel were turned and milled from one solid piece of steel. It’s one of the reasons these rifles were too expensive to manufacture.

The front sight is the typical brass bead (you can sort of see it in the featured photo at the top of this blog), which I usually don’t like, but with these results I can’t complain. I’ve shot better groups with two or three other open sight rifles using jacketed bullets at 100 yards; this is the best any cast bullet has ever done for me.

Popups: Click on them to keep us going!

Want to see the first installment of the Eleanor story? It’s right here.

Check out our other guns and reloading articles here.

Tough to get to a gunstore to buy targets? Range fees for targets too high? Do what I do and order them online. They’re delivered right to your door and they’re less expensive, too.

Need a calipers for measuring your group size? This is a great place to find great calipers

at a great price.

Want to check out Montana Bullets? Here’s a link to their website. Tell them Joe sent you. Trust me on this: These are best cast bullets I’ve ever used.

Never miss an ExNotes blog! Subscribe for free!