So this all got started on a trip to Baja. My beloved ’92 Softail started clanging and banging and bucking and snorting somewhere around Ensenada. I was headed south with my good buddy Paul from New Jersey (not the Paul I grew up, but another one). It was obvious something wasn’t right and we turned. It wasn’t the end of the world and the Harley did manage to get me home, but I could tell: Something major had happened. The bike was making quite a bit of noise. I had put 400 miles on it by the time I rode it back from Mexico. I parked the Harley, got on my Suzuki TL1000S, and we changed our itinerary to ride north up the PCH rather than south into Baja. That trip went well, but there was still the matter of the dead Softail.

Here’s where it started to get really interesting. My local Harley dealer wouldn’t touch the bike. See, this was around 2005 or so, and it seems my Harley was over 10 years old. Bet you didn’t know this: Many Harley dealers (maybe most of them) won’t work on a bike over 10 years old. The service manager at my dealer ‘splained this to me and I was dumbfounded. “What about all the history and heritage and nostalgia baloney you guys peddle?” I asked. The answer was a weak smile. “I remember an ad with a baby in Harley T-shirt and the caption When did it start for you?” I said. Another weak smile.

I was getting nowhere fast. I tried calling a couple of other Harley dealers and it was the same story. Over 10 years old, dealers won’t touch it. I was flabbergasted. For a company that based their entire advertising program on longevity and heritage, I thought it was outrageous. Chalk up another chapter in my book, Why I Hate Dealers.

A friend suggested I go to an independent shop. “It’s why they exist,” he said. So I did.

There was this little hole-in-the-wall place on Holt Boulevard in Ontario, in kind of a seedy part of town, near where the local Harley dealer used to be. The Iron Horse. You gotta love a shop with a name like that. The guy who ran it was a dude about my age named Victor. I could tell right away: I liked the shop and I liked Victor. I got my Harley over there and I stopped by a few days later to hear the verdict: The engine was toast.

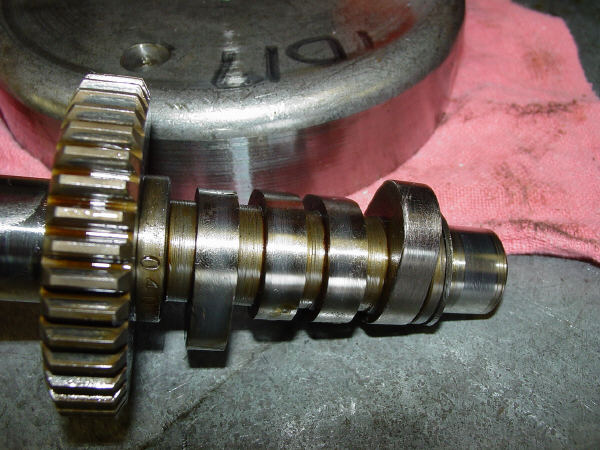

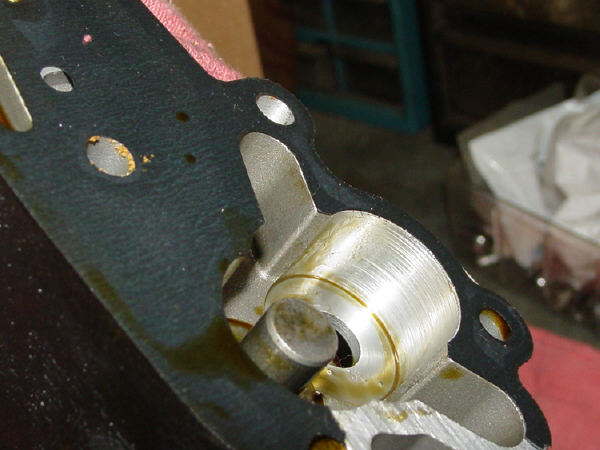

“What happened here,” said Victor, “is that one of your roller lifters stopped rolling, and it turned into a solid lifter. When I did that, the cam and the lifter started shedding metal, and the filings migrated into the oil pump. When that stopped working, the engine basically ate itself….”

“You’ve got lots of other things not right in your motorcycle, too,” Victor explained. “The alternator is going south, your cam got chewed up, the oil pump is toast, the belt is tired, and you’ll probably want to gear it a little taller to reduce the vibration like the new Harleys do.”

Victor gave me a decent price for bringing the engine back to its original condition (in other words, a rebuild to stock), but it wasn’t cheap. Then he offered an alternative.

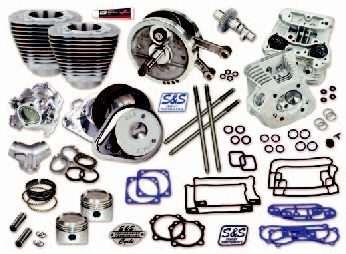

“I can rebuild it with S&S components for about the same price,” he said, “and that’s with nearly everything new except the cases. We’ll keep the Harley cases because then the engine number stays the same, and it’s still a Harley. It would be a 96-inch motor instead of an 80-inch motor, and I think you’d like it. It would be about the same price as rebuilding it with Harley parts. You’d get new pistons, rods, flywheels, and nearly everything else. I’d have to take the cases apart and get them machined to accept the S&S stroker crank and cylinders, and we’d reassemble it with new bearings. Oversized S&S forged pistons would go in with a 10.1:1 compression ratio, and that means you’d have to run high test. Oh, yeah, there’s new S&S heads, a new manifold, and a new S&S Super carb. And an S&S cam.” Then he showed me the components in a brochure, and another chart that showed the difference in power.

It was an easy decision. For the same money it would cost to bring the Harley back to stock, I could get it redone as a real hot rod. For me, it was a no-brainer. My days of bopping around on a 48-hp, 700-lb Harley would be over. The horsepower would double. Bring it on!

My Harley was still running on the original belt drive, and I had Victor replace that, too. And as long as the belt was being replaced, I went with Victor’s recommendation to swap to taller sprockets. That would give the bike a bit more top end and cut some of the vibration at cruising speeds.

I wrote a check and asked Victor to call me when the parts came in. I wanted to photograph the whole deal. Victor said he would, and I stopped at the Iron Horse frequently over the next several weeks.

I was enjoying this. The parts didn’t come in all at once, and that was fine by me. I enjoyed stopping in at the Iron Horse and taking photos. It was something I looked forward to at the end of each day. It was really fun as the motor came together. Victor asked if I wanted the cylinders and cylinder heads painted black like they originally were, or if I wanted to leave them aluminum. It was another no-brainer for me: Aluminum it would be!

One day not long after the motor went together I got the call: My bike was ready. It was stunning and I rode the wheels off the thing. Here’s the finished bike…my ’92 Softail with the S&S 96-inch motor installed.

The S&S motor completely changed the personality of my Harley. I had thought it was quick when Laidlaw’s installed the Screaming Eagle stuff back at the 500-mile service, but now, at 50,000 miles with the S&S motor, I wasn’t in Kansas anymore, Toto. In the 14 years I had owned my Harley previously, I had just touched 100mph once. Now, the bike would bury the needle (somewhere north of 120mph on the Harley speedometer) nearly every time I took an entrance on to the freeway. This thing was fast! Fuel economy dropped to the mid-30-mpg range, but I didn’t care. My Harley was fast! The rear tire would wear out in 3,000 miles, but I didn’t care. The Harley was fast! It ran rich and you could smell gasoline at idle, but I didn’t care. Did I mention this thing was fast?

You might think I would have kept the Harley and put another zillion miles on it, but truth be told, my riding tastes had changed and I only kept it for another year after the rebuild. I was riding with a different crowd and I had a garage full of bikes, including the ’95 Triumph Daytona 1200 I’ve previously blogged about, my Suzuki TL1000S, a pristine bone-stock low-mileage ’82 Honda CBX, and a new KLR 650 Kawasaki. You wanna talk fast? The TL and the Daytona were scary fast. Yeah, the S&S was a runner, but fast had taken on a new definition for me.

And then one day, it happened. My wife had asked me to pick up something at the store while I was out seeking my fortune on the Harley, and when I came home, I realized I forgot to stop for whatever it was. I could have gone out on the Harley again, but for whatever reason, the KLR got the nod instead.

The bottom line: I had back to back rides on the S&S Softail and the KLR, and that’s when it hit me: I had bought the KLR new for about what I had in the S&S motor. The KLR was quicker at normal speeds, it handled way better, it was a much smoother and more comfortable, and it was more fun to ride. That was a wake-up call for me. The Harley went in the CycleTrader that day, and it sold the day after that. Regrets? None. I’d had my fun, and it was time to move on.

Want to never miss an ExNotes blog? Sign up here…