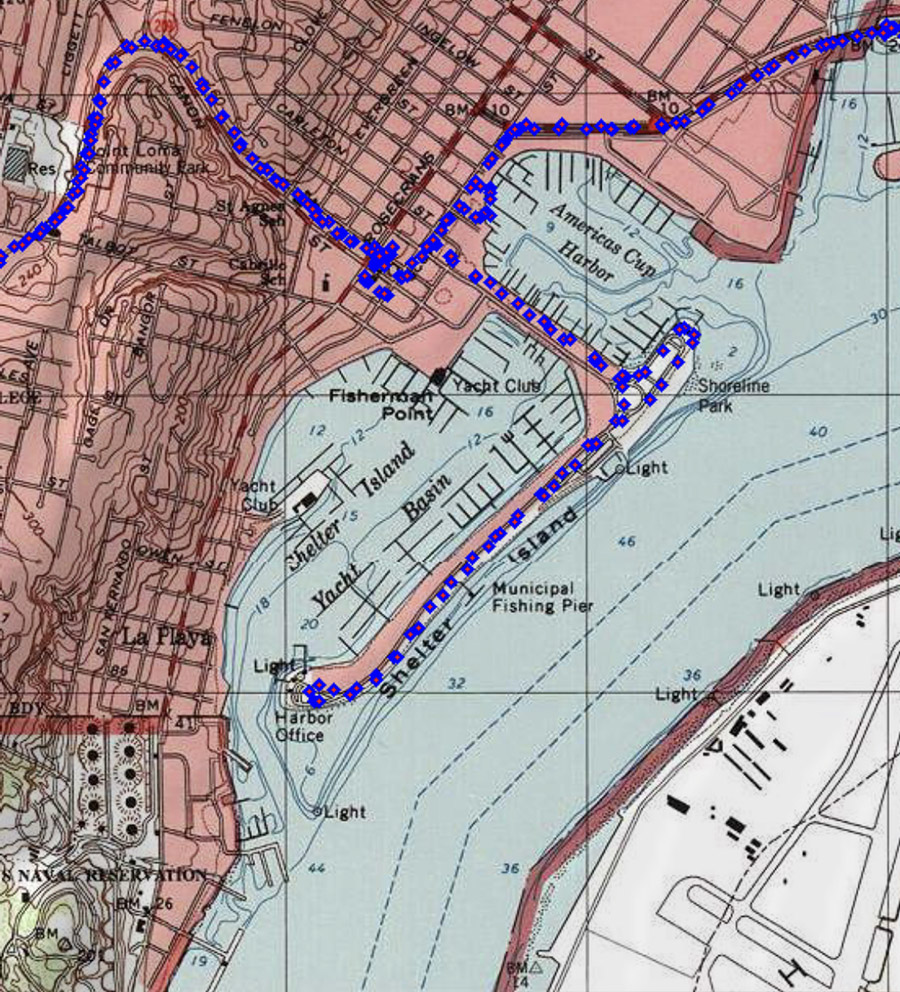

One of the influential people in my life was Woody Peebles. Woody worked at Admiralty Marine down on Shelter Island in San Diego, California. Woody lived on the ocean side of Point Loma in a beautiful, two story home that overlooked the Pacific Ocean. My memory is slightly faulty but I think he was one of the principals, or maybe the owner of, an electronics company called Wavetek. When I started working at Admiralty he was no longer involved with Wavetek and was essentially retired. Woody didn’t need any money; he was well off and I think he hung around boats just to be near people. He was an outgoing personality and chatted a lot.

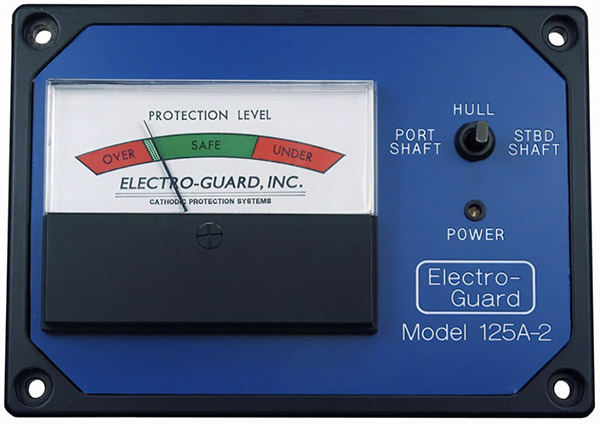

Woody was an electronics genius, which is different from electrical wiring like the Saturn 5 is different from a bottle rocket. We didn’t work together at first. He did electronics and I worked in the mechanical side of Admiralty Marine. The shop began selling a lot of Onan generators and also installed Electroguard corrosion control systems. Woody was having a hard time keeping up with the growth in that end of the business so I’d get pulled off my mechanical duties to help Woody.

Helping Woody was about as much fun as you could have and still call it work. In the morning we would load up the truck for our day’s jobs and take off from the shop like we meant business. Within a block or two Woody would say, “I’m a little hungry. Want to stop and get breakfast?” Of course I did. We’d pull into a restaurant, settle into a booth, order coffee and shoot the breeze. That would be my second breakfast but I could eat all I wanted and never gain weight.

After an hour or so we would go to the actual job. At noon we would knock off early to beat the lunch rush and we haunted The Red Sails Inn nearly every day. They had a really good house salad with a great salad dressing that made me wheeze. Must have been the nitrates. Rosie was our waitress. We would ask which table was Rosie’s and then go sit at that table.

Besides eating, Woody would take the time to explain complex electronic circuits to me while we were supposed to be fixing some poor bastard’s boat. He was forever drawing out circuits on napkins that had nothing to do with the job at hand. It was like a free, college-level electronics course so I lapped it up. I learned about wave soldering, circuit board etching and to think of a printed circuit board as one component, a single part, instead of a collection of electronic bits.

Woody was never in a rush; his concept of time was a revelation to me. Before Woody I was always on someone else’s time, hurrying and stressing to not be late; pressing to meet some other guy’s idea of how long a job should take. I didn’t own my time. Woody had an entirely different way of marking time. He would step into or out of the workday with ease. Sometimes he would just leave the job we were on, “I’ll be back later.” and off he would go.

Working with Woody made me realize that my time was as important as the next guy’s. Jobs weren’t something you did in a fixed amount of time. In fact, time itself became irrelevant and you measured success by completing the work, not beating the clock. If we were taking too long on a particular job I’d start fretting and Woody would say, “Don’t worry about it, I won’t charge for my time.”

This fungible sort of timekeeping was a fundamental change in my concept of income. Before Woody, I was always trying to work more hours to make more money. Once I learned that I could bend time to my will I no longer needed an hourly job. I didn’t need a business to pay me by the hour. In fact, the hour, my benchmark for self worth, was nothing but a man-made denomination. Days weren’t 24-hours long any more, there was only breakfast, lunch and dinner.

My new way of thinking made it possible for me to quit Admiralty Marine and start a boat repair business. I still kept track of my time and charged by the hour but the pressure was off, I could always adjust the bill later. Customers didn’t tell me how long I had to do a job, I told them what I was going to charge them regardless of the hours involved. I may have run out of time on a job but I never fell behind again: I was always right where I should be.

Woody and I left Admiralty Marine around the same time. I started Gresh Marine and tripled my income on the very first day and I was still billing half of what Admiralty was charging for my time. Woody hooked up with Wayne and Walt, also known as the Gold Dust twins. The Gold Dust twins were independent operators who had a loose affiliation when one or the other needed a second set of hands. The three W’s formed a company called Associated Marine but it was mostly in their minds. Each W did their own thing and would bill each other if they assisted on a job.

Woody must have missed me because after a year or so the three W’s asked me to meet with them to discuss a merger. I went to the meeting. The deal was, Associated Marine was going to rent a building at a marina on Mission Bay. All four of us would split the rent, insurance and other business costs. We would still be independent operators with the added benefit of having a crew you could call upon if you needed help for a big re-wire project or a new boat build.

Wayne, a tall, gangly guy told me that I’d have to raise my rates to make them compatible with the rest of the Associated Marine members. They didn’t want me undercutting them. This meant another doubling of my income. Thus began a several year run of bliss. I loved having a shop to work out of instead of my tiny basement. I met my future wife. I bought a house and my first brand new motorcycle. I spent money as fast as I made it but I was young: that’s what young folks are supposed to do.

Bit by bit, Wayne and Walt sent Woody and I out on more of their jobs. They kept us very busy, so busy we never had time to build our own customer base. I began to realize I had switched from working for Admiralty Marine to working for the Gold Dust twins. Maybe that was their plan all along. Still, the money was good and I was having fun working with Woody so I kept at it.

We never had a receptionist at Associated Marine. An answering machine handled incoming calls and if anyone of us were in the shop we’d answer and take notes. One day I walked in the shop and Wayne’s daughter was in the office manning the phones. We didn’t pay her much but it was another cost of doing business.

Walt wanted an outboard motor dealership so he managed to get Suzuki to make us dealers. Then we needed inventory. With the Suzuki’s came warranty work, which was paperwork intensive. I became an outboard motor mechanic even though I hated the damn things. These changes happened without my input. I was too busy working on Gold Dust jobs.

Then came Woody’s son, Woody Junior. Junior had lost his sales job and crash landed at Associated Marine. Junior was outgoing and gregarious even more so than his dad. Now when we went to breakfast there were three of us. And here I was thinking I was the son, you know? But Junior was the real son. He knew nothing about what we were doing at Associated Marine yet he was charging the same rate as the rest of us. Three men on a job was a bit much so Woody and Junior worked together just like me and Woody used to. I worked alone.

There was a bit of tension in the air. I felt Junior hadn’t paid his dues and was starting on third base so to speak, a base that had taken me many years of hard work to step on. Besides, he stole my Daddy and talked too much.

The situation gnawed at me and I became disgruntled. I mentioned to Wayne that since Junior was charging the same as the rest of us he should pay one-fifth of Associated Marine’s expenses. This blew up big time. Woody charged into a boat where Wayne and I were working and grabbed me by the shirt. “You little shit, stirring up trouble!” Woody screamed at me. Junior was behind me sheepishly saying, “C’mon dad, leave him alone.”

Woody was old and had a dicky heart. I was young and strong. It would be no contest. I was getting angry at him shoving me around by my shirt. I balled up my fist to smack him in the jaw and when he saw that he got even more enraged. “Don’t raise your fist to me!” he shouted, like he was yelling at his own son. My fist went down on its own accord. I thought it would have been nice if my fist had informed me in advance that it wasn’t taking my side. My initial anger had subsided and I was sad and worried that Woody might have a heart attack. Woody stormed off the boat with Junior staying a safe distance behind. Wayne was dazed, “What the hell was that?” He said. I didn’t understand the situation at the time but I had gotten the attention I desired.

You know how they say to be careful what you wish for? After a week or so Woody cooled off and apologized for shoving me around. He told me that he’d thought it over and that I was right. Junior became a partner in associated Marine and assumed his fifth of the expenses. Junior had breezed into the Majors without spending a day in the minor leagues.

From then on I generally stayed out of trouble and just worked but it wasn’t nearly as much fun as the old days. Woody, Junior and I did a few big boats together but Junior’s work ethic grated on my nerves. Junior became a passable electrician when he applied himself except he was always talking. I didn’t mind carrying Woody because I could do the work of two men. Junior was one body too many. I finally drifted away from Associated Marine and restarted Gresh Marine as an independent business.

I tried to find Woody online but came up with nothing. . He would be around 100 today so he’s probably not with us. Junior is still alive and living in San Diego. When I first met Woody all I could see was dollars per hour. I wanted a job, any job. I wanted to work for someone. I needed someone to tell me what to do next. After Woody and I parted ways I felt that there was nothing I couldn’t do and I feared nothing business-wise. After Woody I never had a job for the rest of my life and I managed to stay busy the entire time. Thanks, old friend.

Never miss another blog:

Keep hitting those popup ads!