By Joe Gresh

I’ve worked in the trades most of my life. I don’t pull that “most” figure out of a hat. It has yet to be determined how my remaining years will be spent but even if I started a new career tomorrow there is simply not enough time left to exceed the 50-plus years I’ve spent doing manual labor, unless I live to 110 years old. So far all the mentors I’ve written about were involved with the line of work I was doing, be it construction, the various marine trades I engaged in or mechanics. Bernie Hunt was a different sort of mentor in that he created an entirely new and unexpected line of work.

Mr. Hunt was the editor of The Key West Citizen, our local daily newspaper way down south in the Florida Keys. For a small town there were a lot of dramatic events happening in Key West seemingly all the time. It was such a clannish place and so vested in the smuggler’s lifestyle that the Feds were constantly blowing into town arresting high officials because local law enforcement was in on the deal, if not outright protecting the crooks. Scandals were plentiful and the news business was hopping.

After one of the many hurricanes that hit our place in Big Pine Key, the whole island was littered with junk. Residents would stack their crap along the roadsides where it sat waiting for someone to haul it away. Big Pine Key was considered The Sticks to Key West and other islands and so we were usually last for any kind of assistance. No matter where you lived in the Keys, local government was slow to react in times of disaster and we had to wait for FEMA to come in and mop up the mess. This took many, many months.

With the stinking piles of trash as a backdrop I wrote a letter to the editor about how the roadside junkyards were a boon to people like me. I found a rare column-shift collar for a three-speed manual transmission Ford Econoline van in the piles. I dug out a nearly complete 1972 Yamaha RT2 motorcycle not far from home. My friends in Big Pine Key called it Beirut Auto Supply because our neighborhood looked like images of war-torn areas in the Middle East.

Help us help you: Please click on the popup ads!

Mr. Hunt called me. He said he wanted to know if I was a real person and that he loved the letter and wanted to make it into a column for the Sunday edition of the newspaper. I was pretty excited. He asked if I could come down to the Key West Citizen offices and meet with him. This was pretty cool considering I was a boat electrician and not a writer.

That’s how I met Bernie Hunt for the first and last time. We chatted in his office and he asked, “What makes you so funny?” I was caught off guard by the question since the Beirut Auto Supply story wasn’t all that hilarious to me. I couldn’t think of anything and I told him that I didn’t know, that I was just writing about how it was on Big Pine Key. I felt dumb as hell.

After a bit more chatting, Mr. Hunt said, “Call me Bernie. How would you like to write a weekly column for us?”

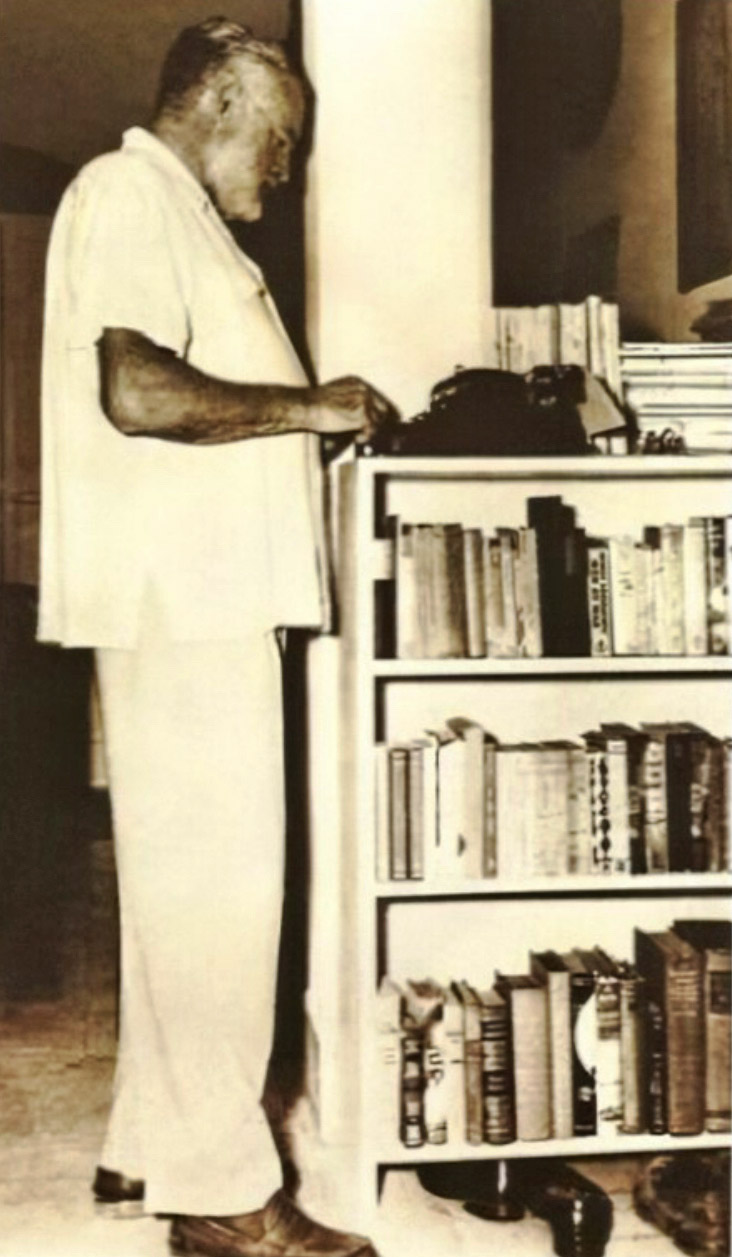

To see how weird this question was you have to understand about Key West’s long, distinguished literary history. The Island is lousy with writers ever since Hemingway drank, fought and typed standing up here. You can’t swing a 6-toed cat without hitting a struggling writer. Taking a chance on a boat electrician with zero writing experience and from Big Pine Key when he had dozens of real writers to pick from sitting on the stoop outside his door was just plain foolhardy.

Brian Catterson, an editor of mine at Motorcyclist once told me that the only correct answer to an editor asking you to write a story is “Hell yes.” I didn’t know that at the time but I still said, “Hell yes.” Bernie took me on a tour of the newspaper building introducing me to the people we met along the way. “This is Joe Gresh, he’ll be writing a column for us,” Bernie would say, like I was somebody they should know. The printing room was an analog delight: huge rollers spun giant coils of newsprint into sheets of printed material. Steel dies were laid out and inked, Bernie complained about how the cost of newsprint had gone up and said they would need to raise the price of a copy if it kept up.

When I got home reality hit: How was I going to write 700 words a week? I bent to it and with a lot of help from CT editing the gibberish I produced we managed to get a Sunday column done. And then we did another. And another. And another.

CT typed my handwritten stories and then faxed them to the newspaper where they would be typeset and printed. Deadline was Friday for the Sunday edition. I wrote about 80 Sunday columns over two years for the Key West Citizen. In all that time Bernie never called me except to say that they couldn’t run a story because it was too weird or for legal reasons. The column received many letters of complaint, which I loved. Bernie never gave me direction, writing advice or told me he liked what I was doing: he just kept printing the stuff.

One day Bernie left for another editor’s job. I lasted a few more editions but the new editor from Ypsilanti, Michigan didn’t care for my shtick and stopped printing my stories. I was never actually fired I was simply ignored. I was pretty burnt out from trying to come up with a topic and write a story each week so I wasn’t too upset about the way it ended.

When I decided to write about him I tried to find Bernie online. I can’t tell if he’s dead or alive. The last place I have him living was Las Vegas, Nevada. I found some phone numbers and email addresses and tried contacting him but no dice. After the Key West Citizen he went on to be editor at many different newspapers and magazines. He even won a Pulitzer Prize (I think), so he’s done fairly well without me. Bernie was the most hands-off mentor I’ve had. His method was to point me in an unfamiliar direction and kick me in the ass. It worked well.

If anyone knows where Bernie is now, do me a favor and send him a link to this story.

Never miss an ExNotes blog: