I’m not a huge fan of Georgia O’Keeffe artwork. Her realistic paintings are well done but the fluffy subjects and flower erotica don’t appeal to my mechanical mind. The bright colors and simple shapes of her later work seem too easy, like anyone could do it. Except anyone didn’t. I suspect art is more complex than a watery brushstroke or an eye for color. It takes a lived life to steer that brush and experience to make the strokes tell meaningful stories. Art matters if people believe it matters and O’Keeffe’s stuff mattered to a lot of people.

Tradesmen like me are work-blind to creation. Wiping a solder joint to leave a clean copper pipe, or combing a bundle of wire so that each conductor peels off in the correct order is as close to art as we get. It’s a tunnel vision that divides hours into effort, a relentless pursuit of money and the next job and then the next. Until you either break down or die.

You can train a tradesman, repetition is the secret to success, but an artist must be born. O’Keeffe was an artist and the way she lived her life was a sort of performance art. She moved to New Mexico in 1949 at the then ripe old age of 62 and spent the next 36 years doing just what she wanted to do. Abiquiu, her home west of Santa Fe was a crumbling wreck when she bought it. The places she stayed became famous simply because she stayed there. She bequeathed to New Mexico a bounty of tourism and spawned museums and visitor centers all around the Santa Fe area.

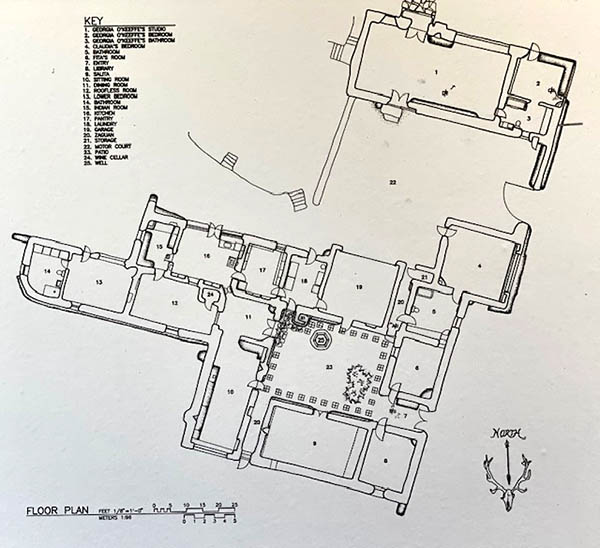

Her place in Abiquiu is a traditional New Mexico adobe house. It has no interior hallways. To get from one room to the next you have to go through another room. Or maybe 4 other rooms depending on how far you are going. It’s not unusual to go through a bedroom, a kitchen and a pantry to get to a main salon. Every room has a door that exits to the outside: You never get trapped in an adobe. A central courtyard open to the sky lies in the middle of the house and the roof slopes towards this courtyard.

The houses were built this way in stages. Maybe one or two rooms to start off with then tacking on extra rooms as money and demand became available. The oldest section of O’Keeffe’s place is from the mid-1800s and the newest probably the 1970s. That’s over 100 years of creeping progress. The flooring transitions from from original smooth dirt soaked with egg yolks to bind the granules all the way to concrete with rug.

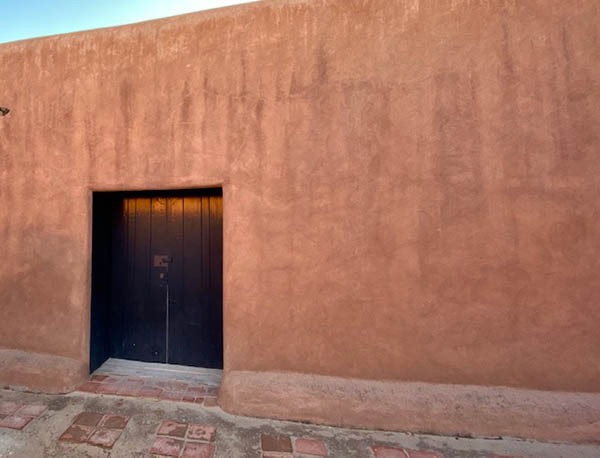

In the recent past people started restoring adobe houses with wire mesh and a Portland cement based plaster. It turns out this is the worse thing to do to adobe. The concrete pulls away from the adobe taking the wall with it. Then moisture and mineral salts wick up into the wall because the concrete doesn’t breathe like mud or lime. It turns into a crumbling mess. If you don’t want the expense of lime plaster, the only way to restore adobe is with more adobe. You slather fresh mud onto the exterior walls on a regular schedule to replace the mud that was ablated during wind or rainstorms. It’s a never ending process but if you stay on top of it your adobe house can last thousands of years. O’Keeffe’s place was concreted at some point. I fear the walls will turn to mush and salts will bleed through the interior walls.

Nothing lasts forever and one day Abiquiu will melt back into the same earth it came from but I hope the artwork created there leaves behind traces, a slight disturbance, a vibration that makes some future traveler pause and wonder what grand endeavors took place way out here in the New Mexico desert.