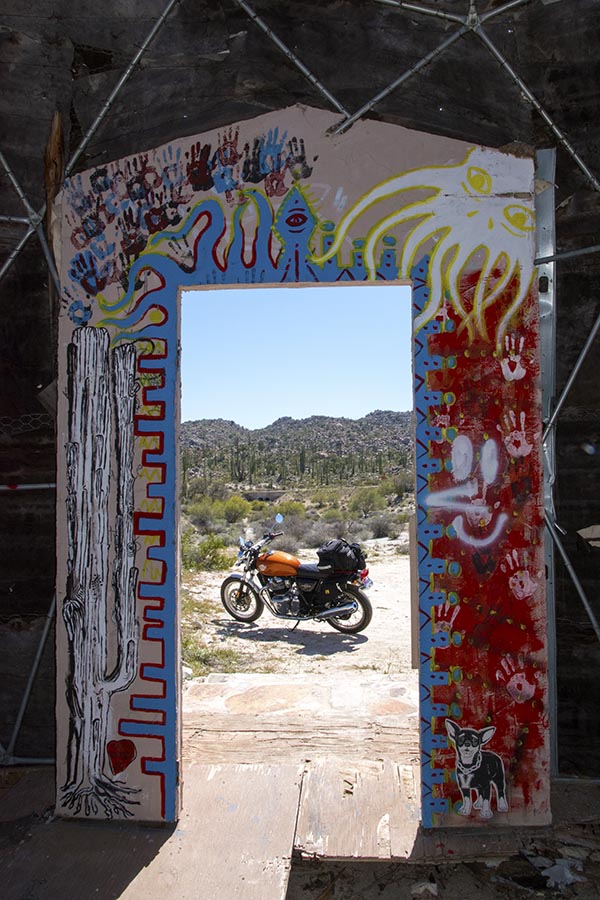

As you’re reading this, Gresh and I are having another excellent breakfast at the Malinalli Sabores Autóctonos restaurant next to the Hacienda Hotel in Tecate, where we arrived last night after another excellent day on the road. As you know, we’ve had a ton of rain this winter, and I’ve never seen Baja so green, orange, and yellow. The wine country south of Ensenada was stunningly vibrant, the orange and yellow wildflowers were in full bloom, the sky was a brilliant blue, and the Interceptor was perfect. Folks, there are few things in life that are as much fun as a Baja motorcycle ride. Doing it on the Enfields was a special treat. Trust me on this.

We rolled out of the Old Mill Hotel in San Quintin late, soaking up the morning sun and enjoying coffee prepared by one of our hotel neighbors. It was an easy run up Mexico 1 and we set a leisurely pace. We encountered the same construction delay in the mountains we experienced on the ride south…you know, one of those deals where they stop traffic going each way while folks going the other way have to wait for all of the other folks who have been waiting. Today was a bit more interesting. As an 18-wheeler passed a trailer (a trailer that was somehow associated with two guys riding BMWs…do the GS models always come with a support trailer?), it hit the trailer on a tight corner. That one could get messy. I hope those riders had their BajaBound insurance. We sure did. I never enter Baja without my BajaBound insurance.

After that, we entered the mess that is Ensenada, but we filtered through it quickly. Then it was on to the Ruta del Vino, a quick stop at the L.A. Cetto vineyards, and back to Tecate.

The Interceptor was just perfect, as it has been on this entire trip. The guys at Southern California Motorcycles in Brea did a fine job prepping the bike for our trip, as was evidenced by the bike’s flawless performance. I’m going to give you my detailed comments on both the Interceptor and the Bullet in a subsequent blog, as will Joe Gresh. This has been a hell of a trip, and it’s not over yet.

Stay tuned, my friends!

Most of our time riding Royal Enfield motorcycles through Baja is spent eating. We have breakfast then ride a while. Any time between 10am and 2 pm is lunch time followed by a rolling dinner that lasts several hundred miles.

Most of our time riding Royal Enfield motorcycles through Baja is spent eating. We have breakfast then ride a while. Any time between 10am and 2 pm is lunch time followed by a rolling dinner that lasts several hundred miles.

Did I ever tell you I’ve been on two boats that sunk? No? Ah well, It’s a story for another blog another day. Bounding out into Guerrero Negro’s bay our low-gunneled pongas were kicking up rainbow waves and a light, salty mist settled over the occupants.

Did I ever tell you I’ve been on two boats that sunk? No? Ah well, It’s a story for another blog another day. Bounding out into Guerrero Negro’s bay our low-gunneled pongas were kicking up rainbow waves and a light, salty mist settled over the occupants.

…and next, some of the photos from our whale watching expedition earlier today…

…and next, some of the photos from our whale watching expedition earlier today…

At one point, we had four whales up against our little boat, all wanting to be petted like giant puppies. One even smiled for us…

At one point, we had four whales up against our little boat, all wanting to be petted like giant puppies. One even smiled for us… Joe and I had a great time.

Joe and I had a great time. After we returned, we had a couple of fish tacos at good buddy Tony’s Tacos El Muelle, and tonight, we’re trying a new restaurant in Guerrero Negro. Tomorrow we’re pointing the bikes north as we head back to California, and most likely we’ll stay in the El Rosario/San Quintin area again.

After we returned, we had a couple of fish tacos at good buddy Tony’s Tacos El Muelle, and tonight, we’re trying a new restaurant in Guerrero Negro. Tomorrow we’re pointing the bikes north as we head back to California, and most likely we’ll stay in the El Rosario/San Quintin area again.

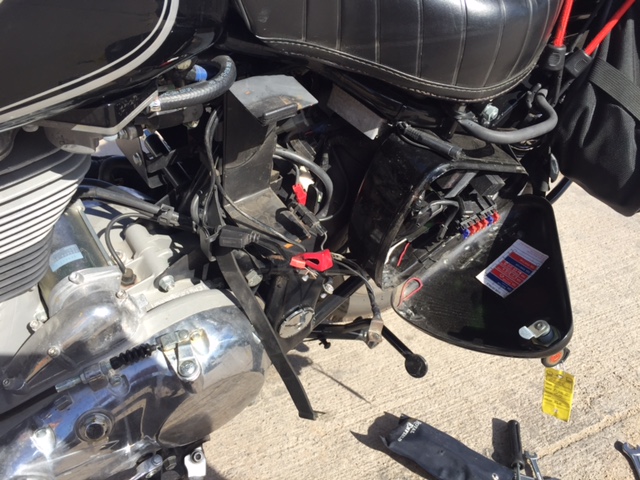

Berk was feeling pretty frisky about the Bullet. We had cleaned up a corroded spark plug cap and the big 500cc single was running well.

Berk was feeling pretty frisky about the Bullet. We had cleaned up a corroded spark plug cap and the big 500cc single was running well. With wires dangling and the larger battery hanging out the left side of the frame our Bullet is looking more like a BMW adventure bike everyday. If we wrapped 75 feet of 3/4 inch electrical conduit around the Bullet you’d swear it was a GS1200. Despite the troubles the thing is growing on us. Really, none of the faults are due to Royal Enfield assemblies.

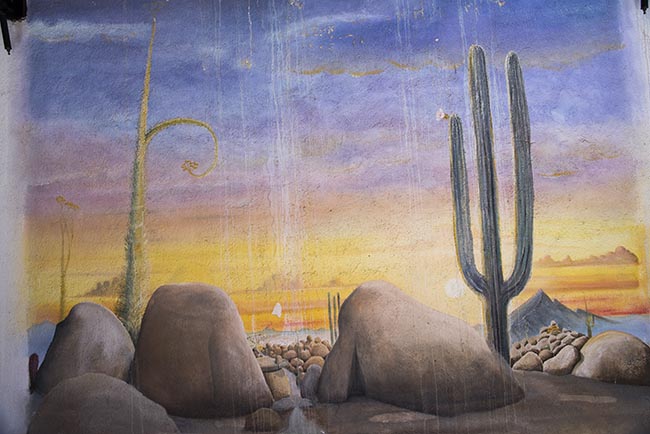

With wires dangling and the larger battery hanging out the left side of the frame our Bullet is looking more like a BMW adventure bike everyday. If we wrapped 75 feet of 3/4 inch electrical conduit around the Bullet you’d swear it was a GS1200. Despite the troubles the thing is growing on us. Really, none of the faults are due to Royal Enfield assemblies. I finally spent some quality time on the Royal Enfield 650 today. We rode from Tecate to San Quintin, Mexico through the Ruta del Vin0 and Ensenada. My initial impressions have been reinforced. Royal Enfield nailed it with the 650 twin.

I finally spent some quality time on the Royal Enfield 650 today. We rode from Tecate to San Quintin, Mexico through the Ruta del Vin0 and Ensenada. My initial impressions have been reinforced. Royal Enfield nailed it with the 650 twin.