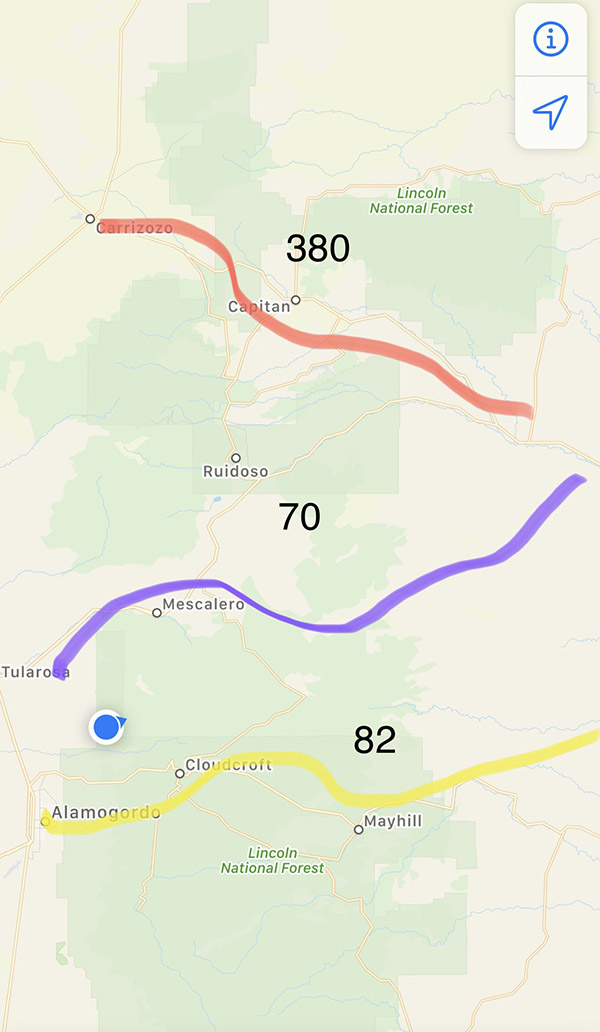

There are three paved routes across the Sacramento Mountains in southern New Mexico. To the north, highway 380 crosses from Hondo all the way to the small town of San Antonio on the Rio Grande River. Thirty miles south is the central road, Highway 70, running from Roswell to Tularosa. Highway 70 is 4-lane all the way and is the main east/west route over the mountains. Another thirty miles further south is Highway 82. Highway 82 twists and turns its way from oil rich Artesia to Cloudcroft at 9000-feet elevation and then runs downhill to the valley floor at Alamogordo. There is another route, unpaved, called 506. Yet another thirty miles south from 82, Route 506 takes you from Queen in the east to the border patrol checkpoint on Highway 54. Not really a highway, 506 is a fairly good dirt road but in the wet it can be tough going. 506 is the lowest-elevation passage as it crosses the southern tailings of the Sacramento Mountains, which flatten out towards El Paso, Texas.

I’m telling you this geographical information because of the tacos. I took the RD350 on a lunch run with the Carrizozo Mud Chuckers the other day. We did a great circle route that brought us to a taco stand in Ruidoso, on Highway 70. This particular taco place was one I had not been to yet. It was rundown-looking and at first I thought it was closed. The front had an enclosed porch area that had 2X6 beams roofed with plywood. One end of the porch was open. The ceiling was low and I could touch the 2X6 beams if I jumped a little. Inside this patio were three wooden picnic tables thickly coated with a gummy white paint.

Dozens of coats of paint left the texture sort of soft, like skin, but more like dried skin. If you stood up fast enough you could just catch the fading impression of denim on the bench seat. To the far right was an entry door. Through this glass entry door I could see an indoor dining room with six, orange, Formica-topped booths but the door to this room was locked.

“Can I help you?” a small plexiglass window swung out into the patio. Inside was the one guy running the taco place. It was my turn to buy so Mike ordered nachos with cheese and a Mexican Coke in the tall, glass bottle except they were out of nacho cheese. I ordered a Pepsi and 3 beef tacos with rice and refried beans but had to order the items individually since there was no meal option. Eddie ordered a single tamale with rice and beans and a Sprite. The order was scribbled on one of those light green paper pads with a piece of carbon paper between the pages for a copy. Our taco man tallied up our stuff in his head and it came to 31 dollars, which shocked me a little. I gave the window guy 2 dollars as a tip. The guy in the window said, “Let me have your name, I’ll call you when it’s ready.”

It’s monsoon season in New Mexico and dark clouds were encircling the taco place. Any direction you looked had rain curtains slanting across the sky. I heard my name called, no mean feat with the thunder, and picked up the order. Eddie carried the drinks. My food came in a styrofoam, 3-compartment box. The main, triangle-shaped compartment held three disintegrating tacos. In the little square area to the upper left was a spoonful of rice, in the right compartment was a squirt of liquefied, refried beans. My tacos fell apart on contact. Mike’s nachos were like tiny burned triangles of cardboard. The nacho cheese would have really helped those chips more than I can say. Mike looked at the chips and said, “I’m not really hungry.” and he shoved the festive, red tub of ashes over to Eddie and me.

The guy in the window leaned out and asked us how the food was. I gave him a thumbs up hand signal. I don’t know why I did that. I guess I should have complained. I figured why spoil the taco guy’s day. If he hasn’t learned how to cook by now he never will make better food and telling him how truly awful the stuff was would change nothing on the ground. We finished up and decided we better make a run for home before it started raining on the taco place. I didn’t like our odds staying under that roof.

By sheer luck I had a rain jacket in the Yamaha’s tank bag. Eddie had a t-shirt and Mike had a semi-water-resistant jacket. To understand how unprepared we were you have to understand the optimism all motorcycle rides start with. We split up, Mike and Eddie turned north towards Highway 380 and I headed directly west on Highway 70. Within a mile it was pouring rain.

Great, horizontal bolts of lightning lit up the dark grey skies. The Yamaha ploughed through deep pools of water hydroplaning slightly and I dropped my speed to allow more time for water to squeeze out from under the tires. At 7600 feet elevation my wet jeans were starting to get cold. The raindrops were huge and felt like pea gravel hitting my hands.

Water trickled in from my ungloved wrists and pooled in the rain jacket elbows. My boots began to fill with water. Past the fire station, Highway 70 begins its descent into Tularosa. Each mile downward raised the air temperature a fraction of a degree. I entered the Mescalero Indian Reservation. Weather-wise, it was still raining but the skies were looking lighter further ahead and I was no longer shivering in my wet clothes.

Both lanes of traffic on Highway 70 came to a stand still. I could see flashing blue police lights reflecting off the wet pavement. It was still raining pretty hard and on a motorcycle you don’t want to be stuck in a line of stopped traffic. The head of the stoppage wasn’t far away so I lane-split between parked cars and the smell of brake linings until I found a gap in front of a late-model, white Chevy pickup. I turned right into the gap at walking speed. The truck driver got on his horn for 10 or 15 seconds to scold me. Here I was, soaking wet, trying to get off the road, while he was sitting snug and dry in his $70,000 pickup. Yet he begrudged me because I got 35 feet ahead of him. What kind of perpetually-miserable person does that? How much better would things need to be for him before he let go of the anger?

I parked the Yamaha at a cut that led up to a wide parking area. Water ran through an earthen ditch, pooled for a moment, and then crossed an asphalt swale before dropping off a tiny waterfall where the undermined asphalt had broken away in chunks, like calving icebergs. There was a guy standing in the rain smoking a cigarette, I asked him if there was an accident. “No, a mud slide has blocked the road.” He said. “The cops say it will be about 30 minutes before the road is cleared.” The man finished his cigarette and flicked it into the ditch where the current swept it down to the pool. The butt eddied several times then floated over the asphalt swale, plunging down the falls and drifted with the current until it was out of sight. The man walked back to his car and got inside out of the rain.

My boots were full of water and my feet needed to dry out a bit so I pulled off each boot and then poured out as much water as I could. Standing barefooted I rung out my socks, then pulled each sock back on followed by the side-specific boot that corresponded with the foot I was working on. Should I turn around and climb 9000 feet to Cloudcroft and home? It would take about an hour of cold, wet, riding. The rain clouds looked heavier in the direction of Cloudcroft and there is no guarantee that route won’t have a mudslide. The rain picked up strength and the blue skies ahead were closing in.

I could go north to Highway 380 and home but that’s back into the main part of the storm and two more hours of cold feet. I‘m nearly home, maybe 40 miles to go. Another cop pulled up and spoke to the one blocking the highway. The first cop started his SUV Ford. It looked like we were getting ready to go. I started the Yamaha; it’s a cold-blooded engine and cools off fast when not running. Steam rose up from the warming engine, fogging my face shield. I could hear cars starting in the line of stopped traffic. The first cop drove down Highway 70 towards the mudslide and the second cop took up his position blocking the highway. And then he shut off his car. I let the Yamaha run a few more minutes then turned it off. A big cab-over box truck turned around and drove away in the opposite direction followed by a new Jeep Wrangler pickup truck. Then some more cars gave up and headed back. I walked over to the new cop and asked him what was happening. “They had the road cleared but another mudslide came across and buried the road.” Across the highway a yellow Case backhoe drove down the wrong side of the road.

“Any idea how much longer?” The new cop said maybe 30 minutes. Things were getting complicated and my calculations began to factor in the road not opening for quite a while. Going over Cloudcroft at night in the rain would not be fun so if this thing went really long I planned on going north to 380 to go south back home, a distance of 110 miles or so. If we could just get a mile or two down the highway I could get on reservation roads and work my way around the stoppage. The rain fell steadily and in my wet clothes I was starting to get a bit chilled so I took a walk to get my blood circulating.

The longer I waited the more I had invested in Highway 70 home. If I had made a decisive move back when we were first stopped I could have been home by now. I was well over an hour stopped and the blue sky ahead was gone, replace by dark clouds. I guess I could go back to Ruidoso and get a motel room for the night. I could dry out my clothes and try again in the morning. Another cop pulled up and spoke to the second cop who looked over to me and said “We’re getting ready to go.” I ran back to the Yamaha and started the engine.

The police cars formed a rolling blockade and the miles long line of traffic followed behind slowly. The mudslide section was still pretty slippery and there were small branches and stones to dodge. Further on we came to another mudslide area but kept driving through the inch-deep goo. A few miles outside of the Indian reservation the road was just wet and the cop cars pulled off the highway. I was at the head of the line, or P1, and no way was I going to let all those cars pass me and kick up a wet fog of water. I spun the Yamaha up to 7000 RPM and the run into Tularosa was fast and violent but I got there first.

It was warm and dry in Tularosa. I backed off the throttle and puttered along at the speed limit. The honking guy in the white truck passed me and then got in front of me. He just had to, you know? I made it home several hours after the Carrizozo Mud Chuckers. They got hammered by the rain also but didn’t have to stop for blocked highways. In retrospect, if I had taken their route I would have been home much earlier but then if I did that I wouldn’t have had anything to write about.

Click on those popup ads!