By Joe Berk

One thing about Ruger: Nobody can top their customer service. Ruger may not explicitly state their firearms come with a lifetime warranty, but in effect, they do.

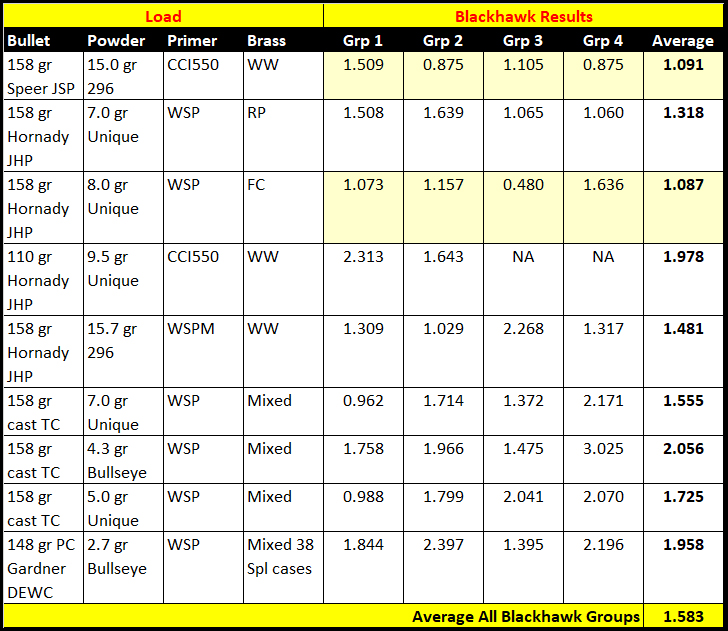

You may remember my story on the Ruger Bisley I won in a Rock Island Auction (I wrote about it several months ago). I had wanted a .357 Magnum Bisley for its heavy construction and longer barrel and, truth be told, I was surprised that my bid prevailed. When I won the Rock Island Auction, I ponied up all the nutty fees that come with such an undertaking (they are significant), and then when I received the Bisley I was disappointed. It wasn’t particularly accurate (the group sizes were mediocre), and it shot so far to the left the rear sight had to be adjusted all the way to the right to get the shots on paper.

I figured I was kind of stuck with the Bisley and my initial thought was I’d look at the gun for a while, stick it in the safe, and then maybe sell it somewhere down the line. But it bothered me. Owning a firearm that doesn’t meet my expectations doesn’t set easy. If there’s such a thing as having an obsessive-compulsive disorder with firearms that are less than perfect, I’d make for a good clinical study.

I wrote to Ruger and told them what I wanted, which was an accurate Bisley that didn’t shoot to the left. I told them the revolver left their plant in 1986, so I was more than willing to pay whatever it took to make me happy. I also mentioned that I wanted to buy new grip frame screws and a new ejector rod shroud (cosmetically, they looked beat up). And finally, I mentioned that extraction was difficult with hotter loads. I asked the Ruger folks to hone the chamber walls so the fired cases would extract easily.

Ruger charged me $45 for a Fedex mailer (which they emailed to me), told me how to package my revolver (a plain brown box, with nothing on the outside to indicate its contents), and advised it could be 4 to 6 weeks before I saw the gun again. Four days later, it was on its way back to me, with no additional charges other than the initial $45 I paid for the Fedex mailer.

Ruger mentioned in the paperwork returned with the gun that they retorqued the barrel, installed a new ejector shroud, honed the chambers, replaced all the grip screws, test fired it, and sent it home. The first thing I looked at was the rear sight. Comfortingly, it was a lot closer to being centered than it was when I sent the gun to them.

So how did it do?

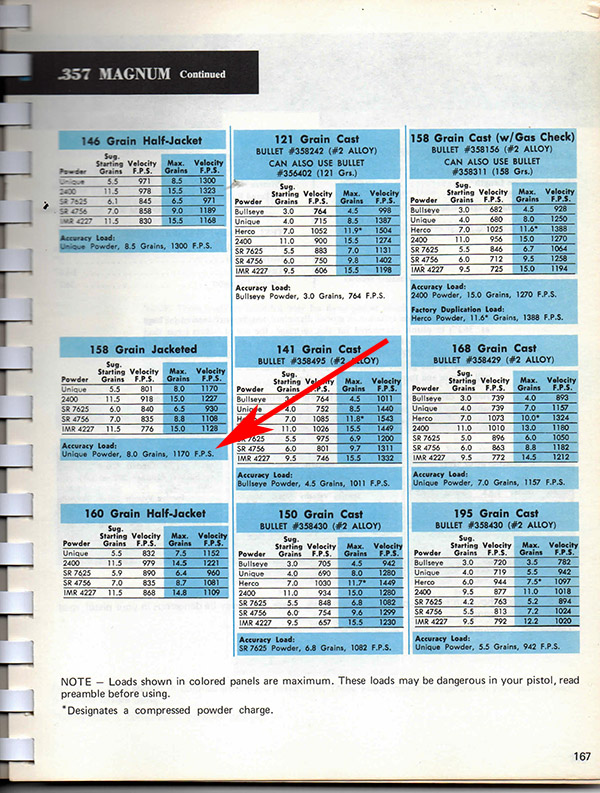

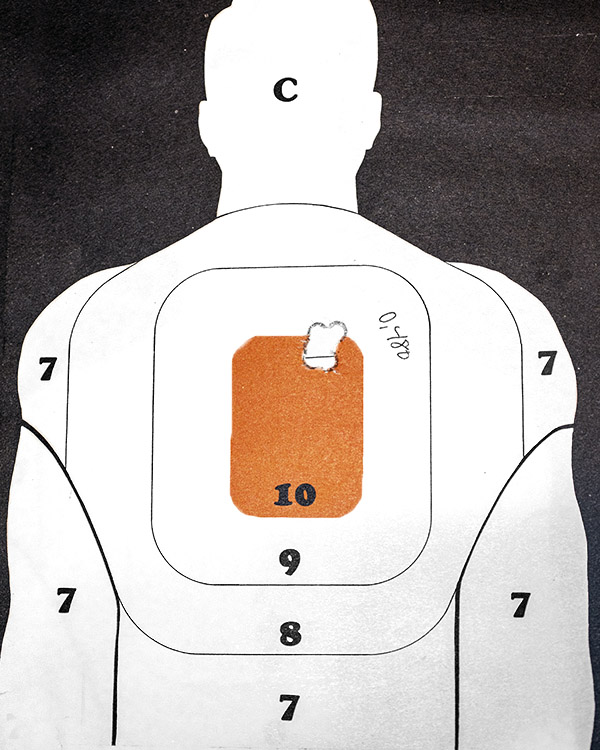

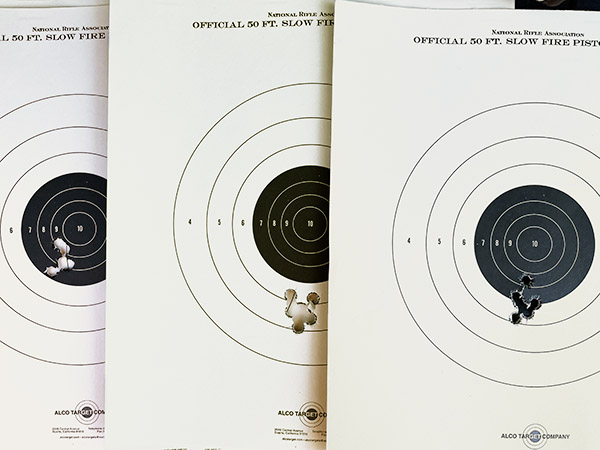

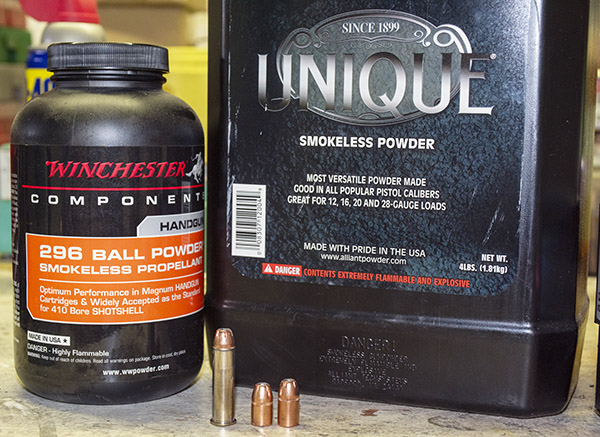

Just fine, thanks. The day I received it, I hopped in the Subie, motored over to my indoor range, and fired three different .357 loads at 10 meters. Now, I know 10 meters is only 30 feet, but I wanted to get an idea how the revolver was working. One load was a relatively mild Bullseye-powered concoction with cast 158-grain bullets, another was a gonzo 158-grain Hornady jacketed bullet load with a max charge of Unique, and the third was an even more energetic load with the same 158-grain jacketed hollow point Hornady bullet and a max load of Winchester 296 propellant. On that indoor range, even with my Walker electronic earmuffs, the concussion of the big Bisley and its full throated .357 loads was starting to give me a headache. But the targets? Oh, boy…the Bisley and I were back in business. I ran another target out to 50 feet (the longest range available at the indoor range), and that group was just as good as the ones at 30 feet.

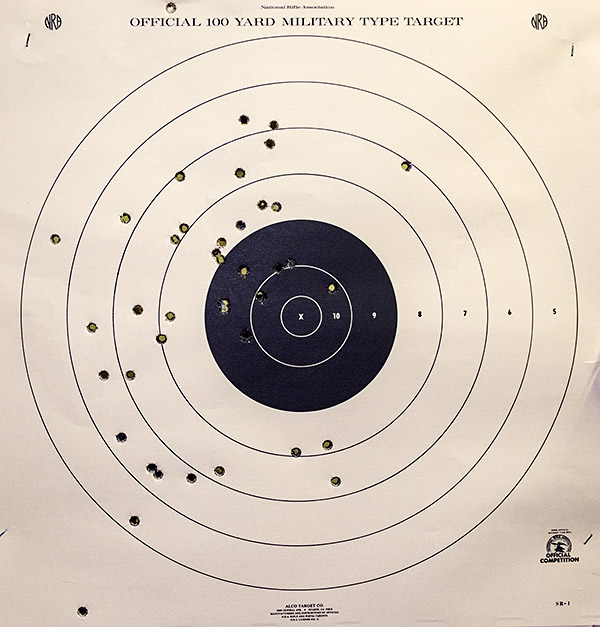

The day after that, I took the Bisley to our Wednesday morning Geezer get-together at the West End Gun Club. I had three things in mind: I wanted to show off a bit to my friends, I wanted to chronograph the two balls-out .357 loads I mentioned above, and I wanted to see how the revolver would do at 100 yards. Yes, you read that right: 100 yards.

My buddy Kevin spotted for me with his spotting scope, and he was amazed with the first load (8.0 grains of Unique and the 158-grain Hornady jacketed hollow points). Kevin gave a hearty “whoa!” and I suspected things were looking good.

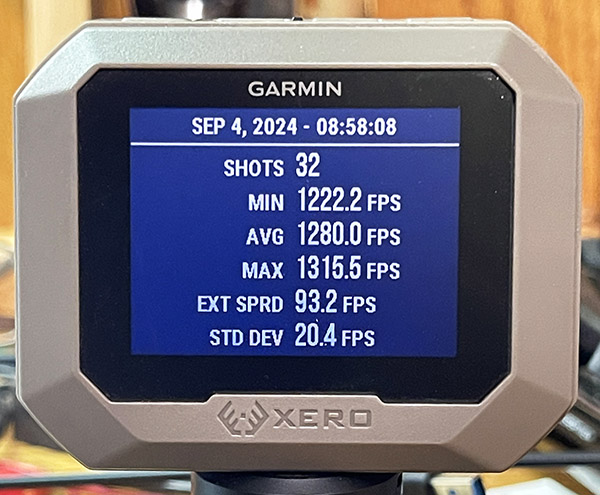

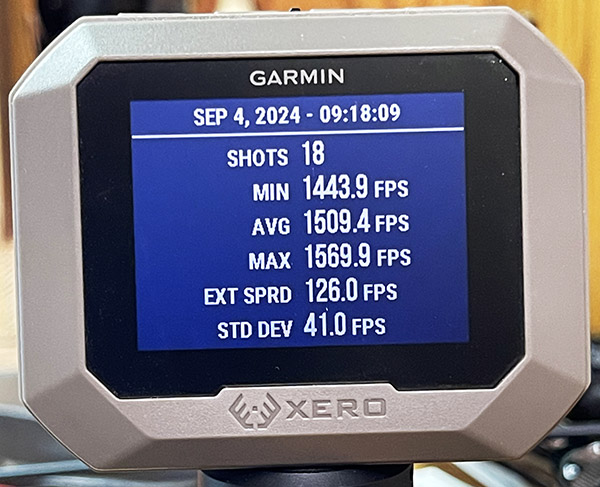

Kevin said several of the shots (after I had warmed up a bit and got into my long-range groove) grouped like I was shooting a rifle. I sure didn’t mind hearing that. I checked the chronograph and the velocities were respectable, too. The bullets were hitting to the left a bit, but I had room to adjust the rear sight to bring that in. And where a gun prints on target is a function of how it is held. I wasn’t consistent with the Bisley yet (I actually haven’t shot it that much).

Then I switched to the heavier-duty 296 load (with the same Hornady XTP bullet), and wowee, I was keeping them in the black on that same 100-yard rifle target. And those loads were smoking hot. Winchester;s 296 propellant is good stuff. Check this out.

All the cartridge cases extracted easily and even with the 1500 feet per second 296 load above, there were no pressure signs (other than a hellacious muzzle blast). As mentioned above, Ruger honed the chambers for me and the prior extraction issues had evaporated.

With replacement of the grip frame screws and the ejector shroud, the Bisley looks like a new revolver. And other than me paying for the initial shipping to Ruger, it was all on the house (Ruger’s house, that is). Bear in mind what I said earlier in this blog: The Bisley, purchased used, is a 38-year-old revolver.

The Bisley went from being a regret to a gun I’m excited about owning. You probably know that Ruger also made these guns in other chamberings, to include .44 Magnum and .45 Colt, and you might be wondering why I wanted the .357 Magnum. Back in the 1970s when I was a handgun metallic silhouette shooter, I competed with a .357 Magnum and I was a rarity. While everyone else was shooting a .44 Magnum or a .45 Colt, or custom-built bolt-action handguns shooting what were essentially rifle cartridges, I was one of the very few people (in fact, the only one I knew of) who shot a .357 Magnum in that game. With the right loads, the .357 would topple the 200-meter rams (the toughest target to knock over) more reliably than either the .44 Magnum or the .45 Colt, so there was a certain coolness (and a bit of smugness) on my part associated with that. The other reason is weight. When Ruger chambers different cartridges in the same firearm, the gun’s external dimensions remain the same, so the .357 Magnum Bisley weighs more than the .44 Magnum or the .45 Colt versions. More weight means the gun holds steadier and that means greater accuracy.

What’s next for this revolver is working up a load with Hornady’s 180-grain jacketed hollow point bullet and 296 powder and getting the sights dialed in at 50, 100, 150, and 200 yards (the four stages of a handgun metallic silhouette competition). When I used to compete in metallic silhouette competition, I used a cast 200-grain bullet, but nobody makes that bullet commercially. Well, almost nobody. I previously found a guy who sold a 200-grain bullet for the .357, but his bullets leaded terribly and accuracy fell off after the first three or four rounds (and cleaning the bore was a pain). If I can get the 180-grain jacketed bullets to group well, I think the metallic silhouette rams at 200 yards won’t know the difference between a 200-grain cast bullet and a 180-grain jacketed bullet, and I may get back in the game. We’ll see.

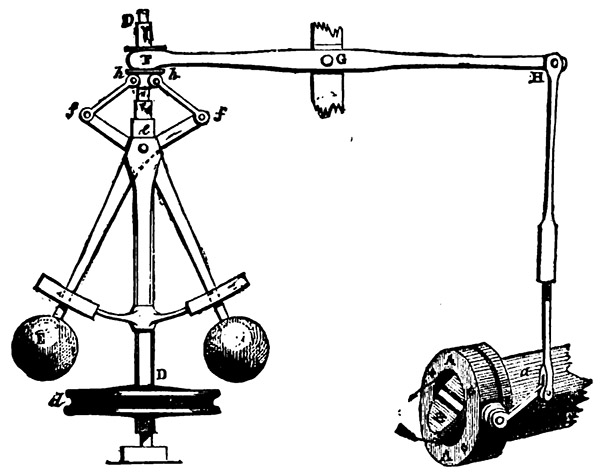

That term: Balls out. You might think it’s a crude anatomical and testicular reference, but it’s not. Engine governors used to use lever-suspended rotating metal balls that moved further away from their axis of rotation as rpm increased. When the engine speed reached a preset maximum value allowed by the governor, the centrifugal outward movement of the balls operated a lever that prohibit engine speed from going any higher. At that point, the engine was running “balls out.”

Never miss an ExNotes blog: