This is the second installment of a story about my grand designs on the 1979 Baja 1000. You can read Part I here.

Feeling the desperate struggle of tiny, ceramic legs, the battle intensified between my digits until I could ignore it no longer. One eye reluctantly slid open. Something was in my hand. I repositioned my arm and uncurled my fingers inches from my nose. There in my palm lay the biggest cockroach I’ve ever had the displeasure of meeting. My brain slammed into gear with a grinding lurch. I hurled the Dreadnought class bug against a nearby wall and surged out of bed, heart pounding from adrenaline. Turning on the lamp I saw two more of his ilk and three ships of the line blinded by the light. Too many lads, I struck my colors and prepared the 250cc for tech inspection.

It seemed odd that while the bike was going through the most demanding vetting, the public course we were racing on was populated by terribly destitute cars wearing dented outboard motor fuel tanks atop their roofs in lieu of proper fuel pumps.

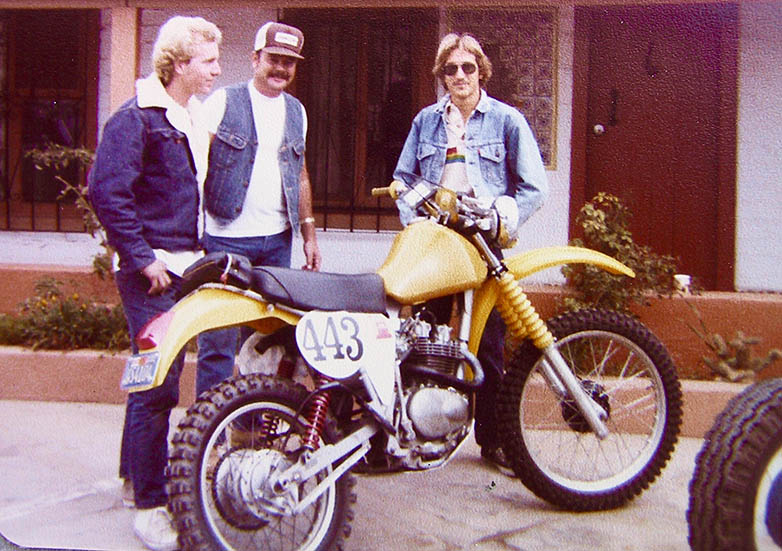

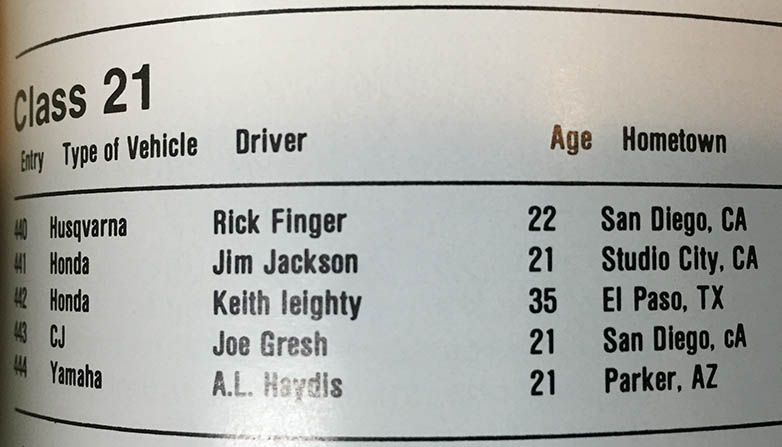

After Tech came Contingency Row. The deal was, you pushed your bike between manufacturers’ tents and they would plaster every square inch of the motorcycle with stickers. If you managed to win the race, money was paid providing the stickers were still visible. Use of the product was not mandatory since all bikes tend to look alike in advertisements. As the used-auto salesmen manning the tents plied their trade, the C&J Honda became laden with colorful vinyl logos. Chase truck driver Greg, Len and I agreed that we were now truly Big Time.

SCORE used a staggered starting system; each rider was flagged off at one-minute intervals. Motorcycles were the first to go, followed one hour later by the four-wheelers. This was done to give the high-powered trucks something to use for traction as they crossed the dusty lake beds at 140 miles per hour.

I was off. Riding through Ensenada past thousands of cheering spectators was unnerving. I had not expected so many people to show up to see me. There’s really no explaining my popularity with the Mexicans. I focused instead on my first problem, vision. I had attached tear offs, (thin sheets of plastic easily removable one by one to provide a clear view) to the face shield of my helmet. Since it was a thousand mile race, I stacked on 50 or so, figuring one for every twenty miles. Looking through the shield for the first time, the scene was a watery blur. I began removing tear-offs singularly then in groups while driving down the parade route. Little kids were scrambling in the street to retrieve my abandoned lenses. Ten miles out I managed to dislodge the final one and could see at last.

Fifty miles into the race the chain broke. I carried spare master links; repairs were made and I was back on the trail before the dreaded four wheelers came. Ten more miles and the chain broke again. I fitted another link as the first of the buggies drove past. A few miles further and the chain broke again. I was out of master links.

Pushing the bike through the sand and rocks, shod in heavy motocross boots, and wearing twenty pounds of leather, I was having trouble maintaining our 25 mile-per-hour goal. The near-constant buzz of four-wheel competitors saw me leaping to the side of the trail frequently. Except for the few motorcycles that started ahead of me, I saw the entire field for the 1979 Baja 1000 go by. I was dead last out of hundreds.

Pushing the bike off-road was hard work. I drank all the water and resigned myself to dying from evaporation. My luck changed, I came upon two campers from the USA who had a Yamaha dirt bike in their van. We talked casually, bemoaning my fate. All the while I was eyeing the chain on their bike.

“I’ll give you a hundred dollars for that chain,” I blurted out. The campers agreed and we swiftly installed the used chain. “Where’s the C-note, Gresh,” said one camper. “I’ll have to pay you back in civilization, I don’t have that much on me.” I gave them my phone number. The campers conferred amongst themselves. Plainly, they didn’t like the turn events had taken. “Why would you offer money you don’t have?” said the other. I made myself scarce before they decided to rob and kill me. That chain was still on the C&J when I sold it.

Any hope of catching the motorcycles long gone, I settled down to a four-tenths pace. I was learning desert savvy quickly: Anytime a large crowd gathered in the middle of nowhere you can be sure a ferocious obstacle was nearby. The locals liked to remove the little red ribbons tied in the brush that indicated you were on the right course. I was fortunate, the field had preceded me and I couldn’t get lost as long as I stayed in the rut.

The first two hundred miles were rough. I picked up ten or fifteen places using my secret weapon, attrition. If everybody broke down I could win this damn thing yet. Past San Felipe the course toughened up. One section called The Staircase was solid rock covered with loose shale. Stepped, square-edged boulders smashed the skidpan while I paddled to stay upright on the marbles. The Baja was working my body like a veteran boxer.

By nightfall I had made 350 miles, more like 400 if you include a 50-mile scenic detour. The thing that wins or loses Baja is lighting. Fully half the race is in the dark. I was running in fourth to rev the alternator high enough for the two 100 watt lights.

My pace dropped off and the crashes, while more frequent, were less painful because I was going slower. Ghostly cactus reached out from the gloom to paw at the C&J’s controls. The thorns stay stuck in your hands even after the main body of the plant is shaken off. Another crash finished off the headlights. I slowed to walking speed and fell again. Far away in La Paz Larry Roeseler and Jack Johnson had already finished on a Husqvarna, dramatically lowering my chances of winning.

I pushed the bike off the trail, leaned it against a cactus, and sat down on a large rock to plumb the depths of my character. It was time to find out what I was made of. Turns out, the abyss of my soul was a mere puddle concealing a shallow tolerance for pain. I sat on the rock and waited the few hours until daylight. The Baja 1000 could go to hell.

Dawn found me raring to go. With the glorious benefit of light I picked up the pace into El Arco, the halfway point, where my relief rider Len was stationed. I couldn’t wait to hand off the bike and turned in one of my fastest times between checkpoints.

In El Arco, Mag Seven installed a new headlight from one of the many wrecked buggies. I didn’t help at all. Peebles Sr. questioned me on how the bike was running. “The bike hasn’t missed a beat,” I told him, “Where’s my relief rider?” Sr. and Jr. looked at each other, “After you didn’t show up last night they figured you must be broken down. They went looking for you.” I wanted to scream Uncle right there but with Sr. and Jr. going over the engine plus all the Mag Seven guys bustling about feeding me coffee and doughnuts, describing road conditions, and generally getting me ready for another five hundred miles, I figured the embarrassment of quitting would be more than even I could stand.

I dropped the bike into first and motored away leaving behind El Arco, security and comfort all because I didn’t want to appear chicken in front of the guys. This kind of reasoning, my mom always said, leads to trouble.

Refreshed with caffeine and sugar, and with the bike handling much better since the boys lowered the fork air pressure from twenty pounds to five, I fell into an easy rhythm. Only one more major crash occurred when I drove off the side of a dry riverbed and impaled the front wheel on the opposite bank. The impact bent the handlebars and the wheel but I survived using a technique I’ve mastered called The Flying Squirrel. The lower Baja course flattened out and several sections along the beach were smoother than California’s freeways. I ran wide open for long periods of time and reached the town of Constitution by nightfall.

They had a nice cookout going at the Mag Seven pit in Constitution. It’s not often you get to sit down to a full meal during a motorcycle race so I couldn’t let the opportunity pass. The clock was ticking but nobody in Constitution pushed me to hurry. I finished dinner and lay down for a minute on an unoccupied camp cot. When I opened my eyes it was morning. The 1979 Baja 1000 was over.

There had been no communication with my team since I left the starting line two days ago. Maybe they had gone on to the finish and were waiting there. The P.T.M. 250 fired up first kick, no excuses to be had, and I continued south to La Paz at a less breakneck speed. Around noon, the team’s black Chevy chase truck loomed into view.

The razzing started immediately. “What took you so long? Were you out for a stroll? What part of “race” didn’t you understand?” Eight hundred miles of desert had proven to me that I was no hero. Our plan was sound, however. Only two 250s completed the course that year, leaving my spot on the podium tantalizingly empty.

“There’s really no explaining my popularity with the Mexicans.”

We need you now more than ever.

Don’t make me cry…

Good Stuff mate!!

Did you ever pay for that chain?

No, they never called me. It was a great chain. Sturdy. Lasted years.