By Bobbie Surber

When is the perfect time to ride Sonora, Mexico? Any chance you get!

Fresh off a ride in Ecuador, I was itching to hop back on my Triumph Tiger GT Pro 900, fondly named Tippi, when my pal Destini (an ace adventure rider) suggested we hit up a rider’s event in Banamichi, Mexico. I did not hesitate for a second. Hell yeah, I’m in!

The first stop on our adventure was a pre-trip visit to Destini’s home in Bisbee, Arizona, an old mining town. Tombstone, a nearby a wine district, and plenty of riding were nearby to keep us busy. Our plan included riding to Agua Prieta, a quick ride from Bisbee, to sort out the next day’s border crossing. With our paperwork ready, we were back on the road aiming for the best tacos in Bisbee!

After enjoying a delicious meal of epic tacos, we gathered in front of the impressive motorcycle shrine at Destini’s (and her husband Jim’s) Moto Chapel. We officially christened Tippi by adding her name to the tank. The Moto Chapel, a vision brought to life by Jim, never fails to catch the attention of visitors. It is a small garage with a pitched roof, complete with air conditioning and even a bathroom. It’s a true paradise for gearheads and motorcycle enthusiasts alike.

On the road again, with Destini leading the charge on her GS 800 named Gracie, we breezed towards the border. Or should I say, Destini and Gracie breezed through, leaving Tippi and me oblivious to the inspection signal, which led to a comical episode of me doing my best to charm the officers while trying to avoid a bureaucratic whirlwind between the US and Mexico. With a little acting (okay, a touch of exaggerated age and frailty), we were back on the road and free as the wind.

We savored every moment— zooming down the desert open roads of Mexico’s Highway 17, enjoying the breathtaking mountain vistas and sweet tight twisties along Sonora Highway 89. That is, until we faced a water crossing. Destini, cool as ever, told me to keep my eyes up and just go for it. Turns out it was a breeze, but then she casually dropped a story about moss and a rider wipeout on a previous ride! Thanks for the heads-up, Destini…you did well telling me afterward!

Our destination was Banamichi, a charming town steeped in Opata indigenous culture and Spanish colonial history. Banamichi was a bustling trading hub, attracting merchants from far and wide. We strolled through its charming streets, greeted by well-preserved adobe houses adorned with vibrant colors and traditional architectural elements. The town’s rich cultural is evident in its festivals, art exhibitions, and handicrafts that highlight its residents’ talent and creativity.

We settled in at the Los Arcos Hotel, hosted by Tom and his lovely wife Linda. Their hospitality matched the hotel’s enchanting courtyard and old-world charm. The weekend whisked by in a blur of exhilarating rider tales, mingling with the aroma of delectable food and more than a few Mexican beers to ease the heat. The morning included a tour by the mayor, including the town square’s church.

Lunch that day included a visit to a small local ranchero for Bacanora tasting. Bacanora is akin to Mezcal, a beverage to enjoy while being careful about how much you are willing to partake! The tasting and lunch were a leisurely affair. We savored the flavors of this year’s Bacanora harvest while enjoying a laid-back lunch with regional dishes that appeared abundantly and effortlessly.

As the sun dipped below the horizon, evenings were a symphony of vibrant hues, margaritas, and captivating rhythms of Folklorico dance. Each of the dancers’s steps told a story—a mesmerizing tribute to Sonora’s rich cultural tapestry.

And as the second night ended, my mind buzzed with the tales of fellow riders and the warmth of the Bacanora nestled in my belly. The air hummed with laughter and camaraderie, each story adding another layer of adventure to the weekend’s memories.

Sunday morning heralded a poignant end to our short escapade—a bike blessing conducted by a local priest. It felt like a closing ceremony, encapsulating the spirit of our epic weekend. As we bid farewell to fellow riders, we reluctantly rode out of Banamichi. Its charms lingered, a reminder of the joy found exploring quaint towns. It was a weekend filled with epic riding, new friendships, and a gentle nudge to continue seeking such delightful adventures.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

Bisbee, Arizona is a late 1880s copper mining town that turned in its explosives, shovels, and rock drills to grow into a more artistic town with historic hotels, quirky shops, and lots of festivals. Being that this tiny community is nestled in the canyons of southernmost Arizona (just minutes from the Mexican border), an idea struck me. I had not visited Mexico since February, and although this sounds crazy, I was craving tacos. Being this close to Mexico it felt almost a necessity to partake in a run to the border to extinguish my craving.

Bisbee, Arizona is a late 1880s copper mining town that turned in its explosives, shovels, and rock drills to grow into a more artistic town with historic hotels, quirky shops, and lots of festivals. Being that this tiny community is nestled in the canyons of southernmost Arizona (just minutes from the Mexican border), an idea struck me. I had not visited Mexico since February, and although this sounds crazy, I was craving tacos. Being this close to Mexico it felt almost a necessity to partake in a run to the border to extinguish my craving.

).

).

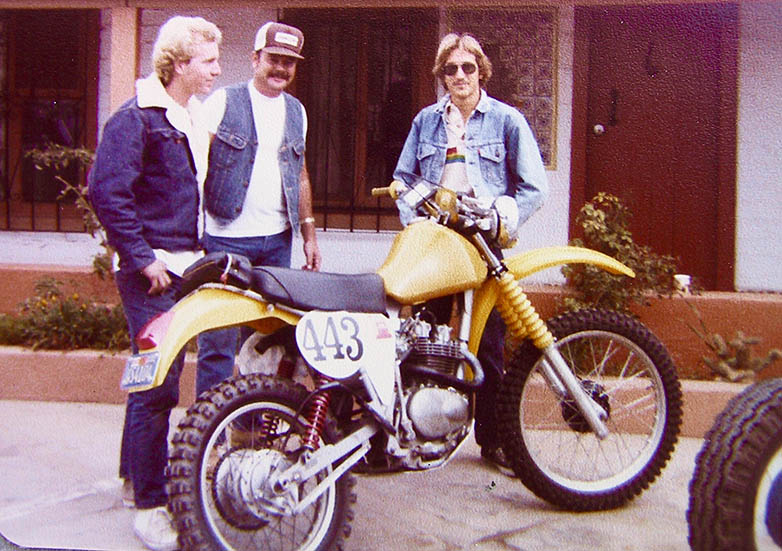

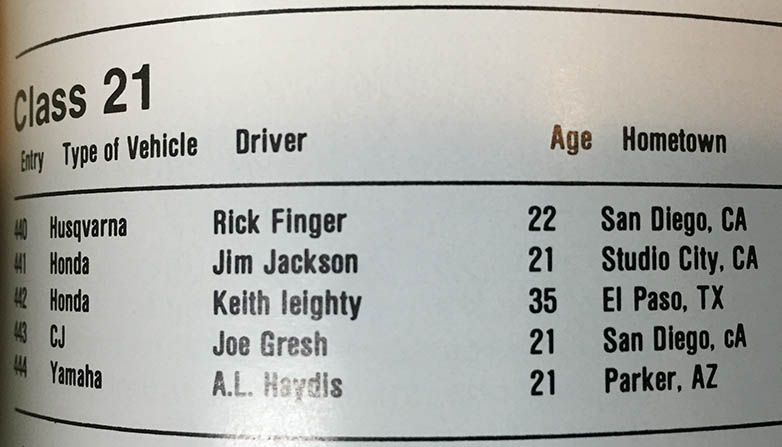

The plan was genius: In 1979 there were only five entrants in the 250cc class. With a historical attrition rate of at least 50%, the Baja desert would do the dirty work. All we had to do was stay together and keep moving. A podium finish was assured. SCORE, the event organizers, made it even easier by allowing a maximum of 41 hours to complete the course. Hell, a 25 mile-per-hour average would do the trick.

The plan was genius: In 1979 there were only five entrants in the 250cc class. With a historical attrition rate of at least 50%, the Baja desert would do the dirty work. All we had to do was stay together and keep moving. A podium finish was assured. SCORE, the event organizers, made it even easier by allowing a maximum of 41 hours to complete the course. Hell, a 25 mile-per-hour average would do the trick.