I wrote a City Slicker press release for CSC Motorcycles last week and it lit up the Internet (you can read it here). The word is out and a lot of people are asking a lot of good questions. One is: How far will this thing go on a battery charge?

I had a lot of fun this morning getting the answer to that question. I was able to play engineer again. More on that in a bit.

Zongshen quotes two figures for the City Slicker’s range: One is a claimed 62 miles in the Eco mode at 20 mph, and the other is a claimed 37 miles at 37 mph in the Power mode. In the ebike world, range drops dramatically as speed increases. Go faster, don’t go as far. Go slower, go further. Hence the two figures.

Today was Phase I of my testing, and it focused on the City Slicker’s Eco mode.

Bottom line first: In the Eco mode, I was able to get 55 miles out of the battery, with the dashboard charge indicator showing 6% charge remaining when the bike shut itself off. I think that’s pretty damn good, even though it didn’t meet the Zongshen claim of 62 miles. I’ll explain why in a bit, but first let me tell you how I ran the test, and before I get to that, let me tell you a bit about charging this puppy.

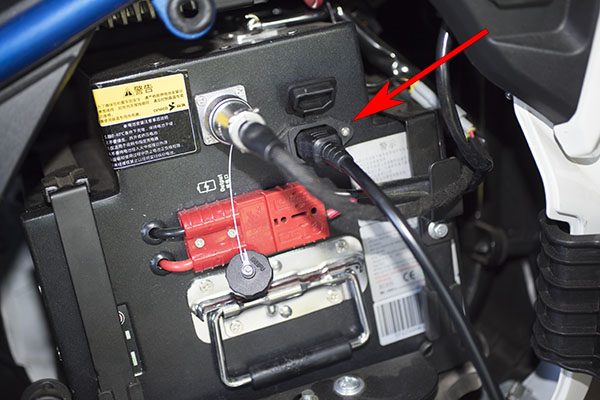

The bike comes with a charger. It’s a big dude, it plugs into a standard 110 VAC outlet, and it takes about 6 to 8 hours to fully charge the battery.

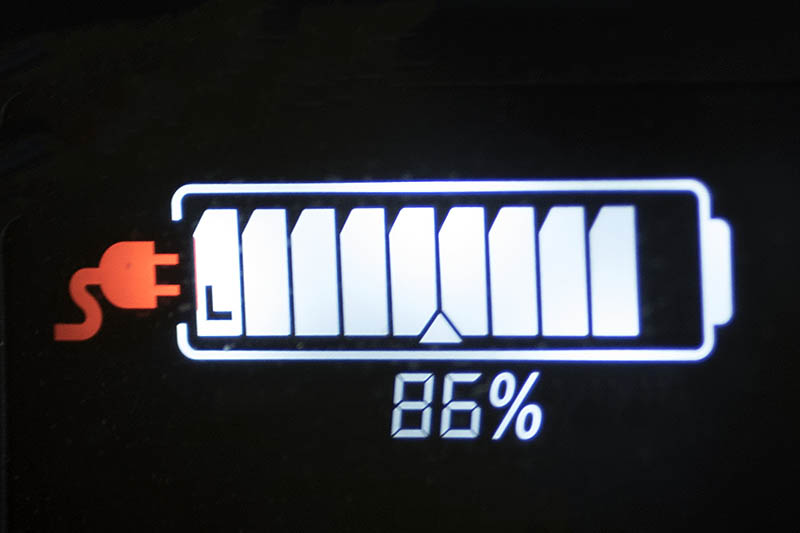

I guess at this point I should tell you that 6 to 8 hours is the right number for a full battery charge. There are folks quoting some clown who said it only took 4 hours to charge the battery (uh, that clown would be me, when I stupidly accepted what someone told me without verifying it myself). My bike’s been on the charger for a little over 3 1/2 hours since I ran the battery all the way down earlier today, and it’s only up to 63%. 6 to 8 hours is the correct answer to this question, folks.

The City Slicker charger has a couple of LEDs on it. One tells you it’s charging and the other tells you the state of the battery charge. If the battery’s not fully charged, that second LED stays red. When it’s fully charged, it turns green.

When you disconnect the charger when the full charge LED light turns green, the bike will indicate a 100% charge on the dash, and it stays that way for a day or two before it starts to drop (if you don’t use the bike). If you leave the charger connected after the LED turns green, it shuts off but it doesn’t keep the battery at 100% until the charger turns itself on again. I think the thing allows the battery to drop to something below 99% before it starts charging again.

I had planned to start my test with a 100% fully charged battery, but it was at 99% on the dash indicator this morning. It was already getting hot here in So Cal and I didn’t want to wait for the battery to get back up to 100%. I started riding with the battery at 99%. Like we used to say in the bomb business: Close enough for government work.

On to the test: I recorded miles traveled at each 1% decrease on the battery charge dash indicator. I wanted to simulate a real world City Slicker scenario, and the course I ran was a 2.8 mile loop around my home. Part of it is slightly downhill, parts of it are steep climbs, and there are 6 stop signs. It’s uphill and downhill, with lots of stop and go in the process. I tried to stick to 20 mph the entire time. It was a good city riding simulation, I think.

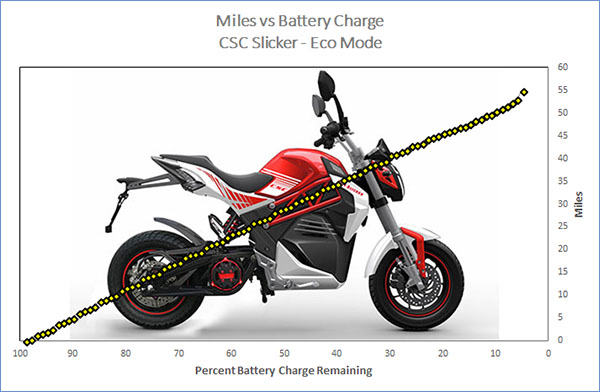

When I finished the run (it took a good 3 hours in 100-degree weather), I then plotted the data. Here’s what it looks like:

My observations and comments follow.

Power consumption as a function of distance traveled was very repeatable. On the uphill portions of the test course, the bike got about 0.4 miles for each 1% of battery charge; on the downhill portions it got about 0.9 to 1.0 miles for each 1% of battery charge. This was very consistent; after a few laps I could predict when the bike would drop a percent on the charge indicator by house number.

I tried to hold my speed at 20 mph, consistent with the Zongshen prediction for the City Slicker’s range in the Eco mode (62 miles at 20 mph). I had a tendency to speed, though, and I was above 20 mph more than I wanted to be.

When the battery charge indicator (on the bike’s dash) hit 30%, the charge plug indicator (on the dash) started flashing red. The concept is similar to the low fuel light on an internal combustion engine motorcycle. It’s telling you that it’s time to start thinking about topping off.

The bike felt like it had normal power levels until the battery charge indicator hit 20%. Below that point, the bike felt like it needed more “throttle” to maintain 20 mph.

At 16% battery charge, things changed. Responsiveness diminished perceptibly. It was in a “limp home” mode, and it would not go much above 15 mph.

The bike became more efficient in the limp home mode. It was going a little further with each 1% battery charge decrease than it had before. Thinking about it now, that’s not surprising, but it surprised me when it occurred.

At 6% indicated charge, the motorcycle had traveled 52.3 miles. It then traveled another 2.7 miles to reach a total of 55.0 miles, where the bike shut down completely. The battery charge indicator was still showing a 6% charge level prior to shutdown. I was thinking maybe I’d get to use that last 6%, but somewhere in that 6% indicated charge level range, it was lights out. Zip. Nada. Nothing left.

My earlier GPS speedometer accuracy testing showed that Slick’s speedometer is about 7% to 10% optimistic (the bike’s speedometer shows the speed to be higher than the GPS showed, which is something I’ve also observed on Zongshen’s internal-combustion-engined motorcycles).

I found the opposite to be true for the odometer. I have a measured mile by my house, and when I covered that distance on the City Slicker, the odometer showed 0.9 miles. I traveled approximately another 250 feet after the end of that measured mile before the odo clicked over to 1.0 miles, so I’m estimating the odometer reading to be about 5% low.

Based on all of the above, I was impressed with the City Slicker’s performance. Zongshen claims a 62 mile range in the Eco mode; I was able to ride 55.0 miles before the battery called it a day. There were several reasons I was slightly under the Zongshen estimated range:

I started with a 99% charge. If I had been at 100%, I would have picked up another 0.4 to 1.0 miles.

As explained above, the odometer registers less than actual mileage. Applying a 5% correction factor, I actually traveled 57.75 miles.

My course had 6 stop signs every 2.8 miles, and I stopped at every one. Accelerating to 20 mph from a dead stop uses more energy than simply riding a constant 20 mph. I stopped and accelerated from 0 to 20 mph 117 times during this test. If the stops signs hadn’t been there, I would have gone further.

My course was uphill and downhill. I’m guessing that this adversely affected power consumption. If I was on a perfectly flat course, I would have gone further.

I’m a full-figured 198 lbs. With my motorcycle gear on, I’m probably pushing 210 to 215. I’ve been to the Mount (that’s Zongshen, in Chongqing) and I’ve seen the Zongshen test riders; they weigh maybe 130 lbs soaking wet. Fat guys soak up the go juice more quickly. With a lighter rider, Slick would have a longer range.

On the other hand, I didn’t have the bike’s lights on. When we get our US-configuration Slickers, the LED running lights on either side of the headlight will be on all the time. That will drop the range a bit. How much is TBD, but when I find out, I’ll let you know.

My next test will be in the Power mode. I guess I’ll be a Power Commander. Stay tuned.

I’m having fun and I’m learning a lot more about electric bikes. You might think riding in circles for three hours would be kind of boring, but I enjoyed it. Folks who saw the bike knew it was something different, which is what I’m getting a lot of every time I ride the City Slicker. The silent riding experience is kind of cool, too. It’s a different kind of riding, and it’s fun. I like the bike. A lot.

If you have questions about the City Slicker, please post them in the Comments section here on the ExhaustNotes blog. I’ll do my best to get answers for you.