Imagine an electric motorcycle that doesn’t look dorky, one that looks like a an ADV bike, with a fit and finish rivaling anything in the world. Before you go all “Ahm a real ‘Murican and yer not” on me, I’m here to tell you this: You don’t have to imagine this motorcycle. It’s real and I rode it. It’s quick and it feels light, and the thing handles. And yes, it’s from China. If that gets your shorts in a knot, move along…there’s nothing for you here.

The bike is the new RX1E from CSC Motorcycles in Azusa, and it’s manufactured by Zongshen. That’s Zongshen, as in million-motorcycles-annually Zongshen. I’ve ridden Zongshen motorcycles all over Colombia, all over China, all over Baja, and all over America, and I’ve been in their factories many times. You may know a guy who’s cousin worked for a guy who thinks Chinese bikes are no good; my knowledge is more of a first-hand-actual-experience sort of thing.

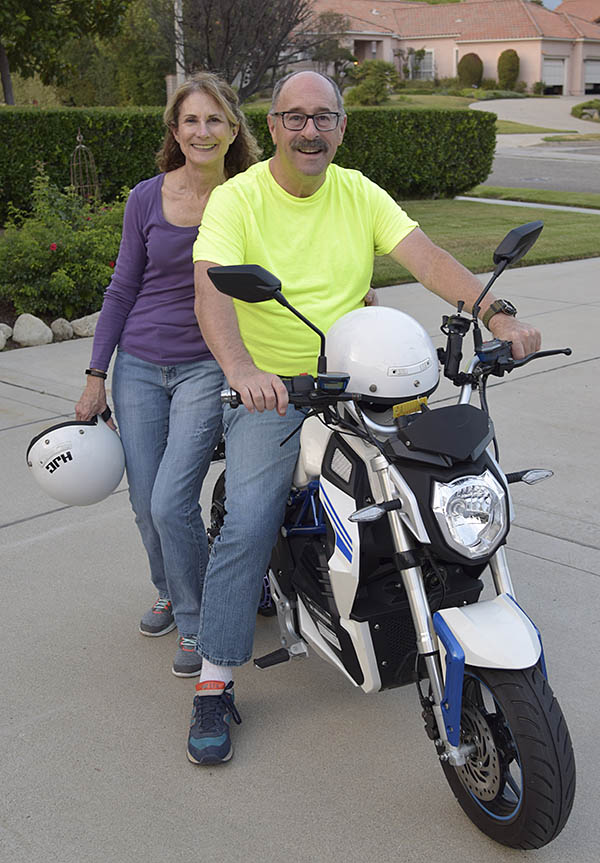

The RX1E looks a lot like an RX3. It’s got the ADV style. I think it is an exceptionally attractive motorcycle. Some folks may wonder why the bike is styled like an ADV bike. Hey, it has to be styled like something. The ADV style has good ergos and good carrying capacity, so why not use that as the styling theme? Just to check, I parked it in front of Starbuck’s, you know, like the big kids do with their BMWs, and it worked just fine.

The motorcycle has an 8 kilowatt motor (with 18.5 kilowatt at peak power), but the kilowatt thing for an electric motorcycle is misleading. This motorcycle is quick. I opened it up getting on the freeway and the bike blew through 70 mph before I realized it. It had more left, but I ran out of space. It’s silent, and you hit speeds you don’t mean to because there’s no noise to go with the acceleration. Think of it as the opposite of a Harley: No noise at all, and lots of acceleration.

It’s not going to be inexpensive, but it’s inexpensive compared to other electric motorcycles. CSC is going to sell a lot of these.

The time for a full recharge, per the CSC folks, is 6 hours. CSC opted for a more powerful charger to get the recharge time down.

It comes with a full set of luggage, crashbars, a windshield, and a cool dash. You can fit a full face helmet in the tail pack.

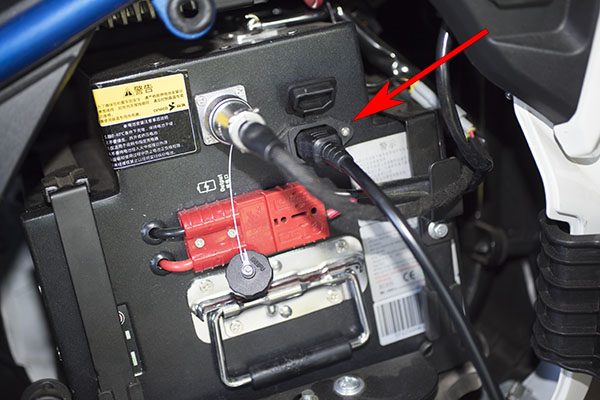

The RX1E is water cooled. Yep, you read that right. The Zongshen wizards use water cooling with a radiator to keep motor temps down.

The dash is cool, and you can change the color theme. I liked it. It was a little difficult to read in sunlight, but CSC tells me that will be corrected by the time the bikes are released for sale in a few months (I rode the first one to arrive in America).

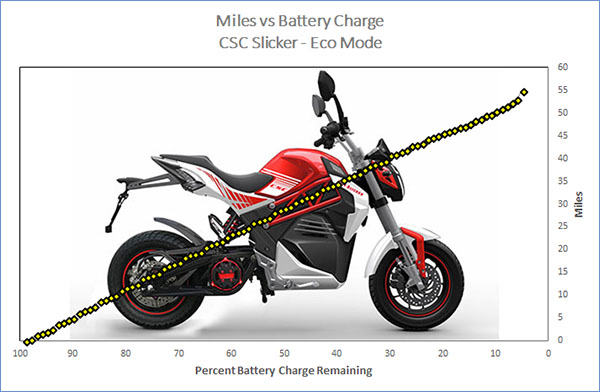

The bike has three modes: Eco, Comfort, and Sport. Eco saves energy, Comfort is kind of in the middle, and Sport gives snappier acceleration. Think of Goldilocks and the Three Bears.

Switchology is superior, in my opinion. Here’s a peek at the left and right sides. Yep, there’s cruise control, reverse, mode setting, high beam and low beam, the horn, turn signals, a park position, and a kill switch. It’s a logical, well thought out, and quality presentation.

The bike doesn’t have that squirt out from under you feeling that other electric bikes have off a dead stop. CSC’s City Slicker had a little bit of that. The Zero I rode a couple years ago had way too much of it…so much so I found the Zero difficult to ride. The RX1E is much more rider friendly.

The bike has disk brakes front and back and ABS. There are cast aluminum wheels. The final drive is via belt. There’s no messy chain, nothing to oil, and it’s quiet. I like it.

The fit and finish are awesome. It’s as good as anything I’ve seen on any motorcycle anwhere in the world. The one I rode was red (it’s the one you see in the pictures here). I saw a Harley chopper and stopped to ask the owner if I could shoot a photo of the the RX1E next to it. He was good to go, and I grabbed the shot you see below.

The RX1E ergonomics felt perfect to me. The seat is comfortable, the reach to the bars was perfect, and I could put both feet flat on the ground.

CSC shows the bike’s weight to be 469 pounds, but it felt way lighter to me. That might be because the weight is down low on this bike. Or maybe I’m just used to my Enfield, which feels way heavier. Whatever it is, the bike feels light. The RX1E has high flickability.

The lack of any noise takes some getting used to. It was unnerving at intersections. On an internal combustion engine motorcycle, the noise makes you at least think other people can hear you. The silence of an electric motorcycle makes you wonder if they see you. Maybe that’s a good thing; it made me even more of a defensive rider than I normally am.

There’s no shifting, and because of that there’s no clutch and no shift lever. Oddly, the lack of any need to shift felt perfectly natural. Not having a clutch lever on the left handlebar when coming to a stop takes a little getting used to.

The bike has a reverse. It doesn’t need one. It felt so light and the seat is so low that backing up the old-fashioned way is easy…you know, sitting on the bike and using your legs to back it up a hill. Yep, I did it.

The turning radius is delightfully tight. I don’t have a spec for this, but I can tell you that u-turns in one-lane alleys are easy. I know because I did it.

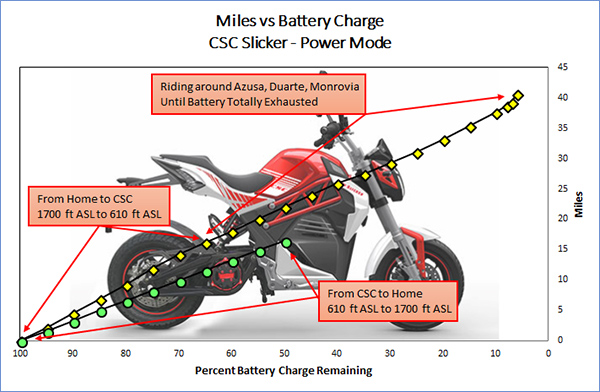

CSC tells me the range is about 80 miles, although the spec below says 112 miles. I haven’t tested the bike for range like I did on the City Slicker because I only played around in town for an hour or so. Good Buddy TK, the sales dude at CSC (who may be the world’s only sales guy who never stretches the truth), has been commuting back and forth to work on the bike and he tells me the 80-mile range is real.

The RX1E impressed me greatly. If reading this blog gives you the impresssion that I really like the RX1E, I’ve done my job as a writer. CSC and Zongshen have hit a home run here. Zongshen’s engineering talent and CSC’s ability to see what the US market wants is impressive.

Spoiler alert: Knowing people in high places has its advantages. I used to be a consultant for CSC, and CSC advertises on the ExNotes site. But that hasn’t influenced what you’re reading here. My friendship with the CSC owners got me an early ride on the RX1E (a scoop, so to speak) and a chance to see the specs before anyone else, which we’re sharing here. They’ll be on the CSC website today or tomorrow.

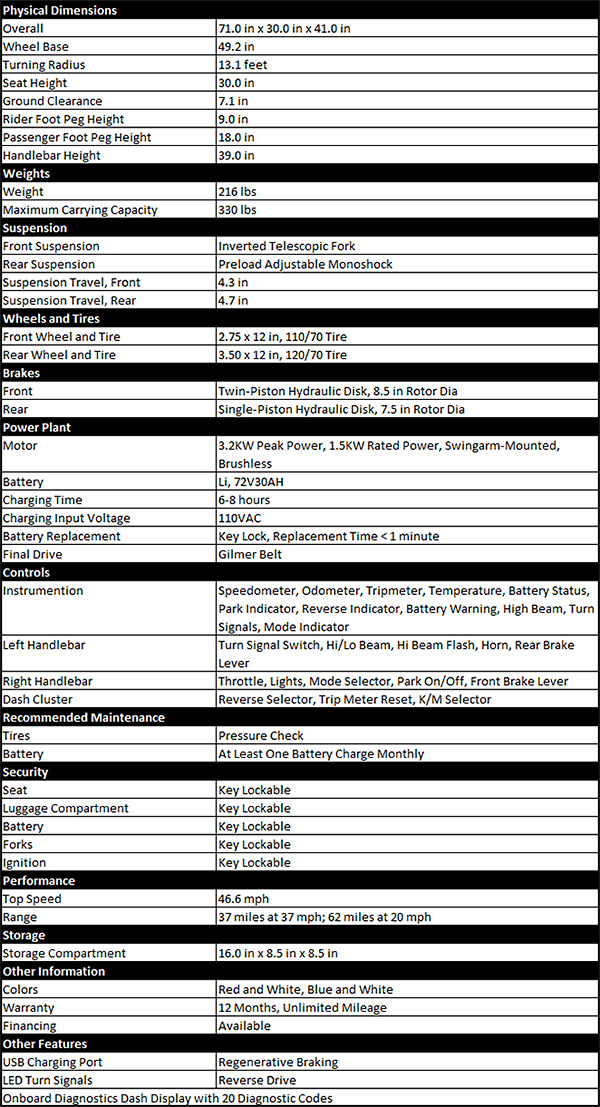

CSC RX1E Specifications

Motor: Liquid-cooled permanent-magnet

Peak Power: 24 hp (18.5kW)

Torque: 61.2 lb-ft (83Nm)

Battery: Lithium-ion 96-volt, 64Ah

Battery Capacity: 6.16kWh

Charger: 110-volt

Input Current: 15A

Range: 112 miles based on New European Driving Cycle (NEDC)

Frame: Tubular steel

Rake & Trail: 27°, 74mm

Wheelbase: 55.5 inches (1400mm)

Front Suspension: 37mm inverted telescopic fork, 4.7 inches travel, adjustable for rebound damping

Rear Suspension: Monoshock, 4.3 inches travel, adjustable spring preload and rebound damping

Front Brake: Two-piston caliper, 265mm disc

Rear Brake: Single-piston caliper, 240mm disc

Wheels: 17-inch aluminum

Tires: 100/80-17 front; 120/80-17 rear

Length: 82.2 inches (2090mm)

Width: 34.0 inches (865mm)

Height: 47.4 inches (1205mm)

Seat Height: 30.9 inches (780mm)

Ground Clearance: 6.0 inches (150mm)

Curb Weight: 436.5 pounds (198kg); 469 lb with luggage and crash bars

Max Load: 331 lb (150kg)

Top Speed: 75+ mph

Colors: Crimson Red Metallic, Honolulu Blue Metallic and Silver Moon Metallic

Price: $8,495 (plus $410 dealer prep, documentation, and road testing fees) and if you order the bike now, CSC is offering $500 off with delivery in Spring 2023

Hit those popup ads and keep us publishing!

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

Any questions? Post them in the comments section, and I’ll see if I can get answers.

Any questions? Post them in the comments section, and I’ll see if I can get answers.