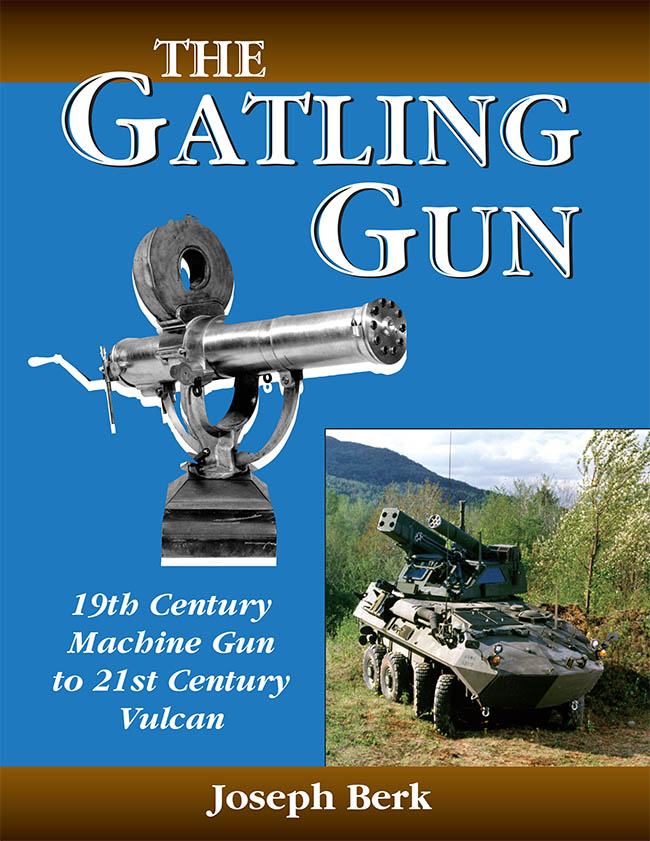

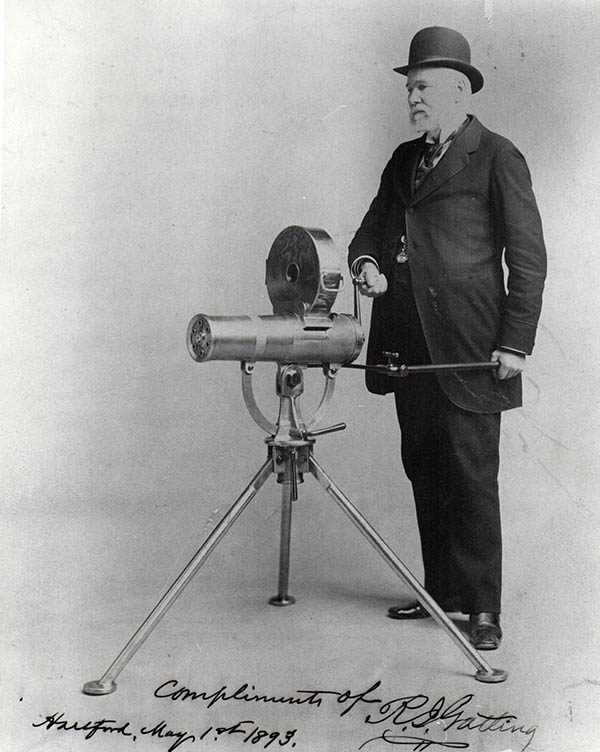

Yeah, I know…a Gatling gun is not a machine gun. It was a hand-cranked weapon back in the day, but it’s still a fascinating a bit of machinery and this Civil War weapon concept is the principle behind modern high-rate-of-fire systems on combat aircraft, helicopters, naval vessels, and more. I was so captivated by the Gatling design and how it extended from the Civil War to modern gun systems that I wrote a book about it (The Gatling Gun). You may have already known that.

Keep us afloat: Please hit those popup ads!

The Gatling gun and its transition from the 1860s to today’s modern combat applications is fascinating. To get that full story, you might want to pick up a copy of The Gatling Gun.

So how did it come to be that modern high-rate-of-fire gun systems use the Gatling principle?

Here’s the deal: Around the end of World War II, jet aircraft entered service, and the old .50-caliber M2 Browning simply didn’t fire fast enough. With the new jets, aircraft closing speeds in a dogfight might exceed 1000 mph (two jets coming at each other over 500 mph), and what was needed was a shot pattern rather than a steady stream of bullets. In searching for higher firing rates, the Army discovered that Dr. Gatling and the U.S. Navy had both experimented with Gatling guns powered by electric motors, and way back in 1898 they attained firing rates over 1000 shots per minute. In 1898, a firing rate that high was a solution looking for a problem that did not yet exist. So, the concept was shelved for the next half century. But after World War II, it was the answer to the Army Air Corps’ jet fighter gunnery dilemma. The U.S. military dusted off the concept of an electrically-driven Gatling, gave a contract to General Electric, and the modern Vulcan was born.

Like I said earlier, the Gatling gun and its variants are used on many different combat systems. One of the earlier ones was immortalized by Puff, the Magic Dragon, in The Green Berets. The Green Berets is one of my all time favorite movies and the scene I’m describing shows up at around 1:20:

The first Vietnam-era gunship used old World War II C-47s (that’s what you see in the video above). Then the Air Force went to the C-130, a much larger aircraft, because it could carry more cannon. Then, because they couldn’t get C-130s fast enough, they turned to old C-119s. When the Air Force did a range firing demo to convince the folks who needed convincing at Eglin AFB, the gunship Gatlings fired continuously until they had no more ammo, and I’m told it was so impressive the project managers secured an immediate okay to proceed. The bigwigs viewing the demo firing thought the sustained burst was all part of the plan; what they didn’t know is the control system malfunctioned and the aircrew couldn’t turn the Gatlings off. Hey, sometimes things happen for a reason.

I know a fascination with Gatlings is unusual, and you might wonder how it came to be. It goes like this: When I was in the Army, my first assignment was to a Vulcan unit in Korea. To ready me for that, I had orders to the US Army Air Defense School’s Vulcan course in Fort Bliss, Texas. Vulcans were the Army’s 20mm anti-aircraft guns, and on the first day of class, the sergeant explained to us that the Vulcan gun system was based on the old Gatlings. Whaddaya know, I thought. The Gatling gun.

Then things got better. After a few weeks of classroom instruction, we went to Dona Ana Range in New Mexico to fire the Vulcan. I thought the Vulcan would sound like a machine gun…you know, ratatat-tat and all that. Nope. Not even close. When I first heard a Vulcan fire I was shocked. If you’ve ever been to a drag race and heard a AA fuelie, that’s exactly what a Vulcan sounds like. I heard one short BAAAAAARRRKKK as the first Vulcan fired a 100-round burst at 3,000 shots per minute. Jiminy! The effect was electrifying. We were a bunch of kids yammering away, and then the Vulcan spoke. Everyone fell silent. We were in awe.

At the Dona Ana range, the effect was even more dramatic…there was the soul-searing bark of the actual firing, and then an echo as the Vulcan’s report bounced off the distant Dona Ana mountains. Then another as the next gun fired, and another echo. And another. Cool doesn’t begin to describe it.

After I left the Army, my next job was on the F-16 Air Combat Fighter, and it used the same 20mm Gatling as did the Vulcan. After that it was General Dynamics in Pomona, where I worked on the Phalanx (a 20mm shipborne Vulcan). Then it was on to Aerojet, where we made 30mm ammo for the A-10 Warthog’s GAU-8/A Gatling. It seemed that every job I had was somehow tied to a Gatling gun variant, and that was fine by me. I loved working with these systems.

And there you have it. If you’d like to more about the different systems using Gatlings today and the early history of the Gatling gun, you can purchase The Gatling Gun here.

Check out more Tales of the Gun!

Hit those popup ads!

Never miss an ExNotes blog: