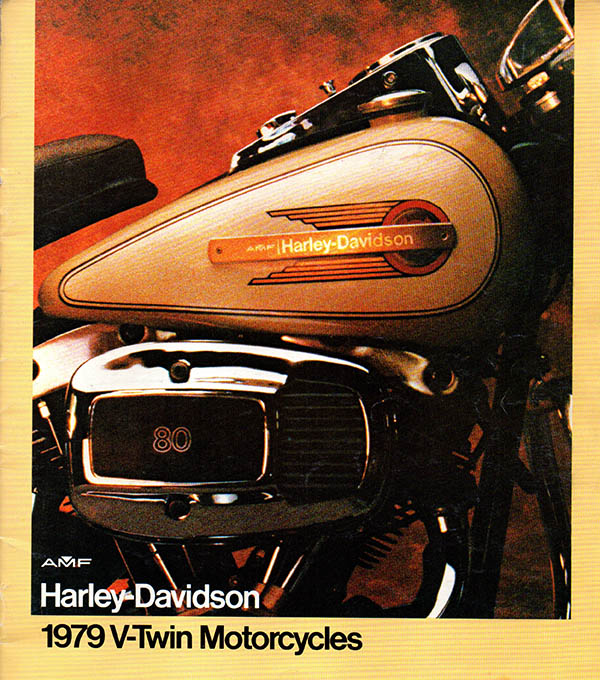

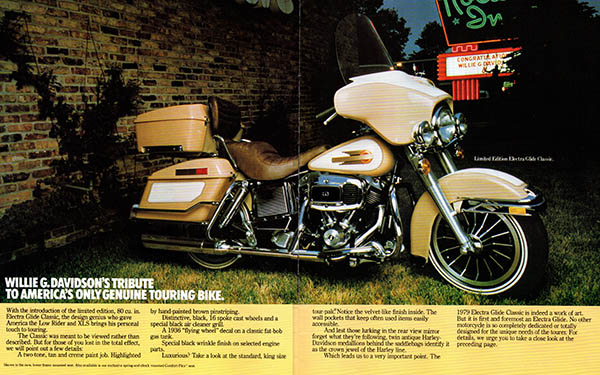

It was beautiful, it was something I always dreamed about owning, and I couldn’t ride a hundred miles on it without something breaking. I paid more for it than anything I had ever purchased, I sold it in disgust two years later for half that amount, and today it’s worth maybe five times the original purchase price. I wish I still had it. I’m talking about my 1979 Harley-Davidson Electra-Glide, of course. That’s the tan-and-cream motorcycle you see in the photo above, scanned from my original 1979 Harley brochure. The motorcycle is long gone. I had the foresight to hang on to the brochure.

All of the photos in this blog are from that brochure. I wasn’t into photography in those days, but I wish now that I had been. The Harley’s inability to go a hundred miles without a breakdown notwithstanding, I hit a lot of scenic spots in the Great State of Texas back in 1979. The Harley’s colors would have photographed well. The only photo I can remember now is one of me working on the Harley with the cylinder heads off. It seems that’s how the Harley liked to be seen. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

So the year was 1979, I was young and single, and I was an engineer on the F-16 at General Dynamics in Fort Worth doing the things that well-compensated, single young guys did in those days: Drinking, riding (not at the same time), chasing young women, and dreaming about motorcycles. If you had mentioned gender-neutral bathrooms, man bun hairstyles, a universal basic income, democratic socialism, sanctuary cities, the Internet, or something called email in those days (especially in Texas), no one would have had any idea what you were talking about, and if you took the time to explain such things, you would have been run out of town after being shot a few times. Texas in 1979 was a good time and a good place.

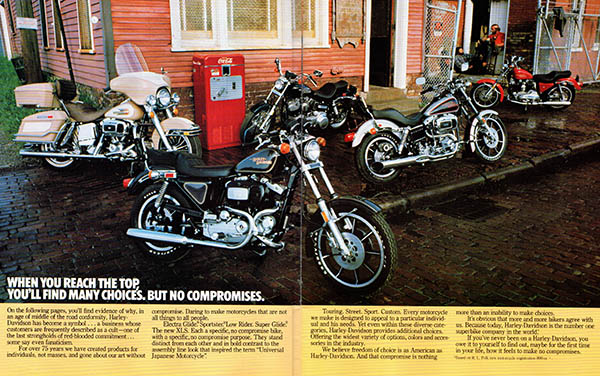

I stopped often at the Fort Worth Harley dealer, and Harley was just starting to get into the nostalgia thing. I had sold my ’78 Bonneville and I had the urge to ride again. Harley had a bike called the Café Racer and I liked it a lot, but I took a pass on that one. Then they introduced the Low Rider and I loved it, but when sitting on the showroom Low Rider I turned the handlebars and one of the handlebar risers fractured (Harleys had a few quality issues in those days). Nope, it wouldn’t be a Low Rider. Then they introduced the Electra-Glide Classic, that stunning bike you see in the photos here. It was a dagger that went straight to my heart. I was stricken.

The Electra-Glide Classic was Harley’s first big push into the nostalgia shtick and it stuck. At least for me it did. My first memory of ever being stopped dead in my tracks by a visually-arresting motorcycle was with a Harley Duo-Glide full dresser when I was a kid (it was blue and white), and the Classic brought that memory home for me. The Classic’s two-tone tan-and-cream pastels were evocative of the ‘50s, maybe a Chevy Bel Air (even though those were turquoise and white, a color Harley later adopted in the early ‘90s with its Heritage Softails). The whole thing just worked for me. I had to have it.

I sat on the Classic and it was all over for me. I fell in love. I knew at that instant that I was meant to be a Harley man. I turned the handlebars and nothing broke. There was a cool old sales guy there named Marvin, and I asked what the bike would cost out the door. He already knew the answer: $5,998.30.

Hmmm. $5,998.30. That was a lot of money. I was riding around in a new CB-equipped Ford F-150 that had cost less than that amount (hey, it was Texas; Breaker One Nine and all that). My internal struggle (extreme want versus $5,998.30) was apparent to old Marvin.

“You know you want it,” Marvin said, smiling an oily, used-car-salesman, Brylcreem smile (these guys all went to the same clothing stores and barbers, I think). “What’s holding you back?”

“I’m trying to get my head wrapped around spending $6,000 for a motorcycle,” I said.

Marvin knew the drill. He was good at what he did. He probably made a lot more money than I did.

“Are you single?” he asked.

“Yep.”

“Working?”

“Yep.”

“Got any debt?”

“Nope.”

“So what’s your problem?”

“It’s like I said, Marvin,” I answered. “I’m trying to justify spending six grand on a motorcycle.”

“You’re single, right?”

“Yep.”

“Well, who do you need to justify it to?”

And, as Tom Hanks would say 30 years later in Forrest Gump, just like that I became a Harley rider.

Yeah, the bike had a lot of quality issues, the most bothersome being a well-known (after you bought one, that is) tendency for the new 80-cubic-inch Shovelhead valves to stick. I first stuck a valve at around 4,000 miles (all of a sudden my Classic was a 40-cubic-inch single, and Harley fixed it on the warranty). I asked Marvin about that, and the answer was, “Yeah, this unleaded gas thing don’t work too good with the new motors. Put a little Marvel Mystery Oil in each of the tanks, or maybe a dime’s worth of diesel, and you’ll be okay…”

Seriously? Marvel Mystery Oil? Diesel fuel?

But I wanted to be good guy, and I did as directed. It wasn’t enough. A valve stuck again at 8,000 miles, Marvel Mystery Oil and that dime’s worth of diesel notwithstanding. Another trip to the dealer, and another valve job. I could see where this was going. The bike had a 12,000 mile warranty.

“So, Marvin,” I began, “what happens the next time a valve hangs up?”

Marvin smiled a knowing smile. “It all depends which side of that 12,000 miles you’re on.” Somehow, Marvin’s Texas accent made it not hurt as much.

Sure enough, at 12,473 miles, a valve stuck for a third time. This one was on me. I pulled the heads, brought them to the dealer, and paid for that valve job. You know, you can just about fix anything on a Harley with a 9/16 wrench and a screwdriver. It was easy to work on. But it wasn’t just the valves sticking. The rear disk brake had problems. The primary cover leaked incessantly. And a bunch of other little things. I’m not kidding. The mean time between failures on that bike was about a hundred miles, and I’d had enough. I called the bike my Optical Illusion. It looked like a motorcycle.

One other thing about the Harley sticks out. I took it with me when I moved to California, and at one of the dealers one of the many times when it was in for service, the dealer’s mascot did what I suddenly realized I had wanted to do. That mascot was a huge, slobbering St. Bernard. It sauntered over to my bike and took a leak on the rear wheel. “Oooh, better hose that down,” the service manager said. “That will eat up the aluminum wheel.” I had to laugh (hell, everyone else was) as the guy sprayed water from a garden hose all over the bike. That dog had beat me to it. He did what I had felt like doing the entire time I owned the bike. The kicker is that even though the service manager sprayed the bejesus out of the bike in a vain attempt to remove all traces of the St. Bernard’s territorial claims, it was all for naught. From that day on wherever I went if there was a dog within a hundred yards, it did the same thing. My Harley was a two-tone tan-and-cream traveling fire hydrant.

Good Lord, though, that Harley was beautiful. Park it anywhere and it would draw a crowd. Half the people who saw it wanted a ride, and if they were female I was happy to oblige. It was big and heavy and it didn’t handle worth a damn, but it sure was pretty. The only time I almost crashed I was riding through a strip mall parking lot admiring my reflection in the store windows. That’s how good-looking it was. I wish I kept it.

Read about our other Dream Bikes!