About 10 years ago the late Jim Cavanaugh and I wrote an article on Mustang motorcycles for Motorcycle Classics magazine. The research for that story was a lot of fun. I thought I’d resurrect it and publish it again here on the ExhaustNotes blog.

The Magnificent Mustang

Mustang: The little motorcycle that could — and still does

Story by Joe Berk and Jim Cavanaugh

Mustang. Uniquely American, the word stirs the imagination. Wild horses. World War II fighters. Pony cars. And for those of us with good memories, some of the coolest motorcycles ever made. No one knows with certainty how manufacturing mogul John Gladden, founder of the Mustang Motorcycle Corporation, selected the name. Some say he thought of wild horses. Others say it stems from the P-51 Mustang fighter plane. Both stories make sense, but we like the one about the P-51. Gladden Products made parts for World War II combat aircraft, so it seems logical that the P-51 Mustang could have been part of the calculus that created the Mustang moniker.

Gladden Products had a lot of things going for it, but as World War II was ending, John Gladden knew he needed a new product. Synchronicity struck when he noticed a very unusual motorcycle in the company parking lot. It was scooter-sized, but it was a motorcycle — a miniaturized motorcycle. The bike belonged to Howard Forrest, a machinist and engineer, and a serious motorcycle enthusiast who constructed it using a water-cooled, 300cc 4-cylinder engine he designed and built himself, from scratch.

So this was the time and the situation, Gladden casting about for a new product, one of his engineers riding a personally-designed and fabricated small motorcycle to work, and millions of young men returning from the war. Gladden recognized opportunity when he saw it: His new product would be a small motorcycle.

Gladden challenged Forrest and Chuck Gardner (a fellow Gladden Products engineer and motorcycle rider) to develop a lightweight motorcycle. Forrest’s 300cc engine was intriguing, but would be expensive to build. Gladden wanted a lightweight and inexpensive bike; more substantive than a scooter, but not as big as a motorcycle — a scooter-sized motorcycle. What resulted was a family of Mustang motorcycles.

The First Mustangs

Mustang originally planned to use 197cc Villiers 2-stroke engines, but after building a few prototypes with the 197cc engine, Villiers instead offered their 125cc 2-stroke. It wasn’t what Mustang wanted, but it was the only game in town. Thus was born the first production Mustang — the 1946 Colt. The Colts had leading-link front forks, a hardtail rear end, tiny 8-inch wheels, a peanut gas tank and twin exhausts. Small, yes, but stunning.

Forrest and Gardner weren’t ecstatic about the tiny Villiers engine, however, and Villiers was making noises about cutting off their supply. Gladden recognized that making his own engines would be critical to Mustang’s success, so Gladden did what moguls do: He acquired an aircraft engine manufacturer that included Busy Bee, a maker of small industrial engines. One in particular seemed a good fit for a new Mustang motorcycle. It was a 320cc flathead single-cylinder 4-stroke, and it became the basic engine that would power future Mustangs.

Forrest and Gardner went back to the drawing board. What rapidly emerged in 1947 was the Mustang Model 2, a completely new Mustang and the first with what we now recognize as the classic Mustang appearance. Bigger than the Colt, it had Mustang’s new engine and 12-inch disc wheels. The intake and exhaust ports faced rearward, with a finned exhaust manifold. The cast aluminum primary cover was adorned with the Mustang logo, and it had a 3-speed Burman transmission, a tractor seat supported by big coil springs, a rear brake, a rigid rear end and telescopic front forks. It weighed just 215 pounds. The Model 2 was not without its problems, however, including rod knocks and noisy timing gears. Mustang handled the issues with special production actions, and to make sure only good bikes left the plant, the production foreman had to personally start, run, listen to, and approve each engine.

More Models

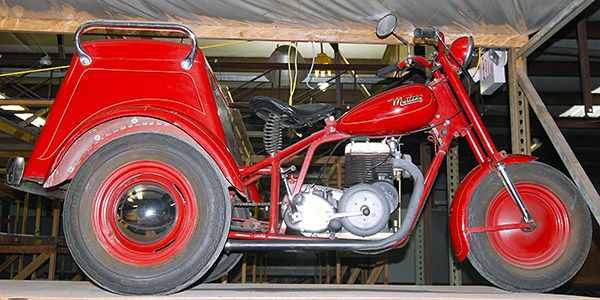

Looking to expand the market, in December of 1948 Mustang introduced the Model 3 DeliverCycle, a three-wheeled, low-cost commercial vehicle. Police departments used DeliverCycles for parking enforcement — the city of Huntington Beach, California, was the first to use trikes for this purpose.

Addressing the Model 2’s problems, in 1950 the Mustang team rolled out the Model 4 (known as the Standard). The newest Mustang engine incorporated Micarta timing gears for quieter running, a new magneto and alternator for improved ignition and lighting, forward-facing intake and exhaust ports to simplify the exhaust design, and a stamped steel primary case. The frame was also cleaned up and it got an improved 3-speed Burman transmission. The new Model 4 sold for $346.30. Mustang rolled these changes into a new DeliverCycle, too, the Model 5.

The Model 4 was a home run, and Mustang used it as the basis for several models over the next decade — the Special, the Pony, the Bronco and the Stallion. The Model 4 Special was a factory performance upgrade with higher compression and hotter cams. The standard Model 4 evolved into the Pony (the base model), which was the best-selling Mustang. Output climbed to 9.5 horsepower. Mustang also offered a 5 horsepower version of its iconic bike to meet some states’ requirements for junior riders.

The Model 4 Special morphed into the Bronco (Mustang had a practice of referring to their bikes with model numbers, which sometimes were offered as Specials and sometimes evolved into other designations). The Bronco kept the Pony’s engine and transmission and added a front brake as standard equipment.

Mustang upgraded the line again with the Stallion (the Model 8). It added a 4-speed Burman transmission and horsepower climbed to 10.5. The Stallion had a chrome flywheel and two-tone paint with pinstriping. The first Stallions had Amal carburetors; later models went to a 22mm Dell‘Orto.

The market started to change for Mustang in 1956. DeliverCycle sales fell and Mustang dropped it. Perceiving a need for a lower cost motorcycle, Mustang introduced a new Colt in 1956, but it was a bust. Value engineered to reduce labor costs, the new Colt had a 9.5 horsepower engine, no transmission and a centrifugal clutch. The front suspension reverted to an undamped leading- link arrangement. The kickstarter was awkward and the centrifugal clutch wore the crankshaft prematurely. It wasn’t liked within the factory and build quality was poor, resulting in rework that offset any hoped-for savings. Mustang killed it just two years later.

Things improved in 1960 with the Mustang Thoroughbred. In a first for Mustang, the Thoroughbred incorporated swingarm rear suspension, a dual seat and an optional storage compartment under the seat. It had the Stallion’s 4-speed Burman transmission and a bump to 12.5 horsepower. This was good stuff, but the 1960s would not be good for Mustang. By the time the Thoroughbred rolled out, Howard Forrest had left the company. The Mustang organization was not without its politics, and for reasons few understood, the company had fired Forrest. Chuck Gardner took his place to lead development.

Offroad Expansion

In 1961, Mustang introduced the Trail Machine, the last in a legendary line of Mustang motorcycles. In a break from Mustang tradition, Trail Machines used Briggs & Stratton 5.75 horsepower engines. Staying with the Burman 3-speed tranny, the Trail Machine looked like the illegitimate child of a motorcycle and a lawn mower, with the standard Mustang diamond tread front tire and a more aggressive tractor tread rear tire.

While the machines were functionally excellent — weight was only 169 pounds dry — the rigid rear Trail Machine was tagged with the uninspiring “Rigid Frame” designation, and when Mustang introduced the swingarm Trail Machine in 1964 it was similarly (and boringly) named the “Rear Suspension” model. These bikes were initially offered only in yellow, but Mustang later added blue. Not many sold, and they are rare today.

Mustang resumed Model 5 DeliverCycle production in 1963, and then quickly upgraded it to the Model 7 in 1964. The Model 7 DeliverCycle incorporated the Stallion’s 12.5 horsepower engine and 4-speed transmission, but time was running out for Mustang. In 1965 production of Mustang motorcycles came to an end.

No one who’s talking knows with certainty why Mustang stopped production. Some say it was because Burman wasn’t supplying transmissions at the required rate. Some say there were management problems. Some believe it was all those nicest people you kept meeting on Hondas, motorcycles that offered electric starting, better performance and lower prices. There were a few revival attempts using residual Mustang parts inventories, but only a handful of bikes emerged. The Mustang saga, one of the most intriguing stories in our magnificent motorcycling world, was over. Or was it? Watch for a near term future blog on the California Scooter Company.

Today, original Mustangs are highly prized, routinely selling for $10,000-plus in concours condition. Even “beater” Mustangs — when you can find them — typically bring more than $5,000. There’s an active fan base (check out www.mmcoa.org), and enthusiasm in Mustang circles runs high.

The Mustang Colt and most of the Mustangs in this feature come from the collection of Al Simmons, the founder of Mustang Motorcycle Products, a designer and manufacturer of aftermarket motorcycle seats and accessories (www.mustangseats.com). An avid pilot, Al named his company after the World War II airplane. It wasn’t until Mustang Seats was well on its way to success that someone suggested he should own an original Mustang motorcycle. Al thought that was a splendid idea. Thirty Mustang motorcycles later, he still thinks it’s a splendid idea.

The late Jim Cavanaugh started in the Mustang Motor Product Corporation’s manufacturing area at age 19 before becoming production superintendent. Jim was an avid rider into his 80s. You might have seen him buzzing around the Oregon countryside on one of his vintage Mustangs or his CSC replica Mustang.

When I wrote the above story for Motorcycle Classics, I was also a consultant to CSC Motorcycles. The initial CSC bike was an updated approximate replica of the original Mustang, and the above story had a sidebar to it that told the CSC story. Watch for it here on the ExNotes blog; we’ll publish that story in another week or so. In the meantime, if you’d like to know more about CSC Motorcycles, their Mustang replicas, and CSC becoming the highly successful North American distributor of Zongshen motorcycles, you should pick up a copy of 5000 Miles At 8000 RPM.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

Keep hitting those popup ads!