Going off-grid requires many design decisions, none of them exceptionally hard or final. With off-grid you can always change your mind to suit your needs although you can save a bit of money if you have a plan and stick with it. Of course that’s not how I do things. I generally screw up and get it right the third time, you know what I mean?

The going native part in the title of this story pertains to base system voltage. In my mind a native setup uses roughly the same voltage for the panels, batteries and inverter as opposed to running high voltage panels and stepping them down to battery voltage.

Going native makes your system more resilient to failure. The two most complicated devices in an off grid system are the inverter and the solar panel voltage regulator (not counting strange new battery technologies). When either of those two fail you are pretty much done until you purchase parts. With a native system the regulator can be bypassed completely by connecting the solar array directly to the batteries. Depending on the size of the array you’ll have to keep an eye on your charging to not overcook the batteries but by simply shading or un-shading a few panels with cardboard you will be able to control the charge rate at a reasonable level.

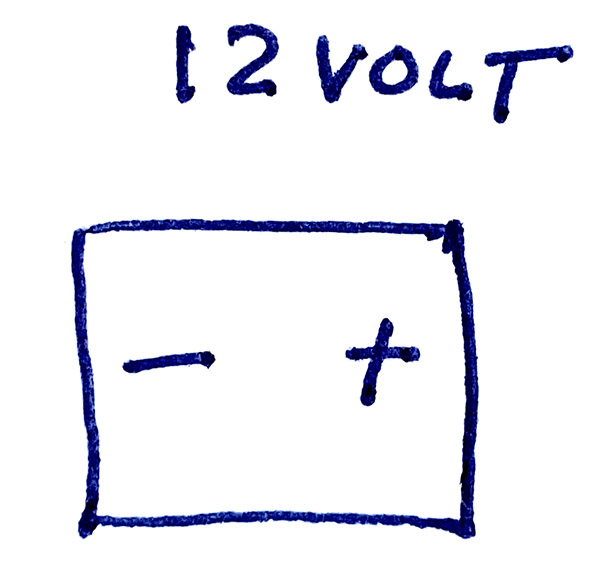

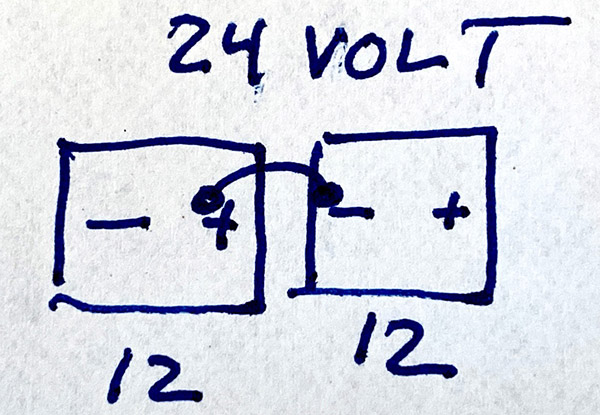

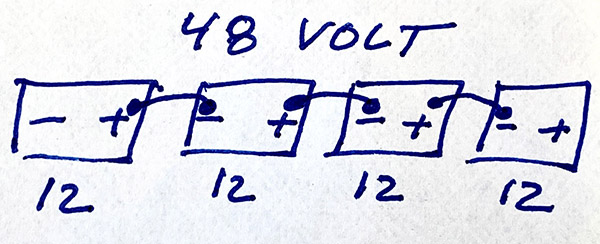

When it comes to common battery voltages for your off grid system you have effectively 3 choices: 12-volt, 24-volt or 48-volt. Fast thinkers will realize that these voltages are all multiples of 12 and that’s because 12-volt batteries are the most popular. You can get batteries in other voltages; there’s no real reason the basic building block had to be 12-volt. You can buy 2-volt batteries all the way to 48-volt batteries.

One or more batteries connected together and powering your house are called a bank and like a bank you have to deposit energy into the batteries in order to draw energy out. For smaller off-grid systems 12-volt battery banks are popular. Inverters in the 2000-watt range powered by a 12-volt battery bank will work fine and are the simplest to connect if you’re electrically impaired. 12-volt banks become less desirable as power needs rise due to the large, expensive battery wires you’ll need to supply the amperage big 12-volt inverters need.

In favor of going native with 12-volt batteries, thanks to the RV industry there are a zillion products that operate at 12-volt. You can get 12-volt refrigerators, 12-volt coffee pots, 12-volt light fixtures, 12-volt pumps, 12-volt air conditioners, 12-volt televisions, 12-volt chargers for your phone and computer and you can even get 12-volt toilets. In fact, you could build yourself a pretty comfortable off-grid house using nothing but 12-volt appliances and skip having an inverter altogether. 12-volt is also fairly safe as your chances of being electrocuted increase along with voltage. Unless you’re really sweaty you can touch both poles of a 12-volt battery and not feel a thing.

The appliances that operate from native voltage will continue to operate with a dead inverter. In my shed that means lights and water pump still work with the inverter shut off. Going native allows you to slowly back out of the complex into the simple and simple things are understandable and reliable.

Going native at 24-volt limits the number of electrical devices you have to choose from. There are not nearly as many 24-volt things as there are 12-volt things. This is slowly changing and 24-volt stuff is becoming more popular. Most DC voltage LED lights are rated 10 to 30 volts. A lot of electronic devices and chargers are also rated 10 to 30 volts (read the fine print on that wall-pig that sucks up all the real estate on your outlets). Getting across 24-volts will give you a tingle and If you’re sweaty you’ll get a shock. Nothing that will kill you, we hope, but still it’s less safe than 12-volt for you electricityphobes out there.

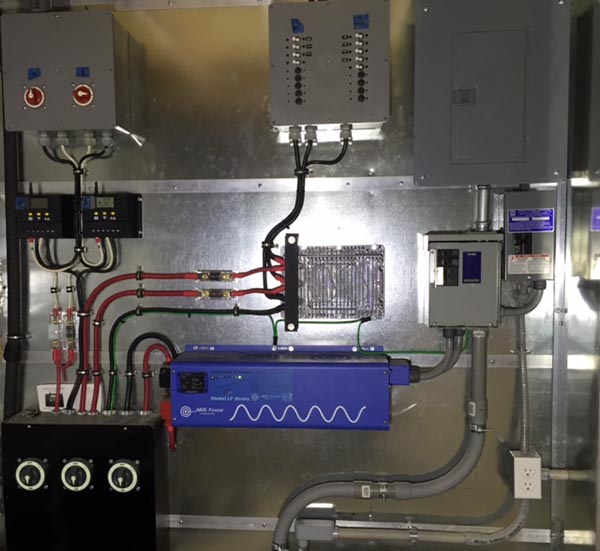

In my off grid shed I’ve chosen 24 for my native voltage, kind of splitting the baby between 12 and 48. My solar panels are considered 24-volt (actually higher but close enough to connect directly). I only really need lights until I can rig up a small inverter to get critical things up and running. The water pump is 24-volt also. My 24-volt inverter is 6000 watts; if I went with a bigger inverter I’d probably go to 48-volt and lose some resiliency.

Going native at 48-volts is sort of useless because you can’t find very many things that operate off 48-volts except inverters. At this native voltage you should toss any hope of backing out of the system gracefully after a lightning strike and put your trust in the thousands of tiny electronic components inside those humming boxes. Go ahead and crank the solar panel voltage up and plan on being in the dark if the inverter fails. Safety wise, 48-volts will give you quite a shock and may even kill you if you are wet and have health issues.

There are devices that will allow you to run most any DC voltage from any other DC voltage. To me these are one more point to fail in the system and they aren’t cheap either. I have one to operate my 12-volt refrigerator from the 24-volt battery bank. It cost almost as much as the fridge!

If you’re planning an off grid system for a remote cabin consider going native. Give yourself the option to keep on keeping on when the buzzing widgets fail. And they will fail. Nothing lasts forever. By building resiliency into the system from the start you can use your head to make things work while others must scamper off to the Internet to order parts.

See Part I of our Off-Grid series!

Unlike motorcycles, I’m not fixated on doing things the old way for electrical energy storage. I run a

Unlike motorcycles, I’m not fixated on doing things the old way for electrical energy storage. I run a  Battery technology is advancing rapidly with so many new combinations of lithium with something else, molten salt or rare elements only found in war torn areas. It’s hard to know which technology will win out in the end but for now, in my solar-powered shed system, lead-acid still offers the best electron storage option.

Battery technology is advancing rapidly with so many new combinations of lithium with something else, molten salt or rare elements only found in war torn areas. It’s hard to know which technology will win out in the end but for now, in my solar-powered shed system, lead-acid still offers the best electron storage option. Lead-acid batteries are easily scalable and nearly any voltage or amperage desired can be achieved with large, simple jumper cables. I’m running 4, group 31, 12-volt batteries in my 24-volt system. My future plans are for 16 batteries total but there’s no rush. I can take as long as I want to get there or 8 batteries might prove to be enough for my usage level.

Lead-acid batteries are easily scalable and nearly any voltage or amperage desired can be achieved with large, simple jumper cables. I’m running 4, group 31, 12-volt batteries in my 24-volt system. My future plans are for 16 batteries total but there’s no rush. I can take as long as I want to get there or 8 batteries might prove to be enough for my usage level. Most important for me: They are cheap! The four deep cycle marine batteries in my off-grid system @100 amp/hour each give me a total of 2400 watts of storage (@ 50% capacity) for 400 dollars. If I ever get to 16 batteries I’ll have 9600 watts of storage for around 1600 dollars. Compare that to 7000 dollars for 7000 watts of storage from Tesla’s Powerwall.

Most important for me: They are cheap! The four deep cycle marine batteries in my off-grid system @100 amp/hour each give me a total of 2400 watts of storage (@ 50% capacity) for 400 dollars. If I ever get to 16 batteries I’ll have 9600 watts of storage for around 1600 dollars. Compare that to 7000 dollars for 7000 watts of storage from Tesla’s Powerwall. I’m not a Luddite when it comes to battery technology on motorcycles or power tools but for me the new designs and materials haven’t yet made sense for large, stationary storage banks at low cost. I’ll revisit the topic if Tesla reduces the price of their Powerwall by half or some new manufacturer comes up with a wiz bang combination of chemicals that outdoes ancient lead acid technology.

I’m not a Luddite when it comes to battery technology on motorcycles or power tools but for me the new designs and materials haven’t yet made sense for large, stationary storage banks at low cost. I’ll revisit the topic if Tesla reduces the price of their Powerwall by half or some new manufacturer comes up with a wiz bang combination of chemicals that outdoes ancient lead acid technology.