Alta, a manufacturer of electric dirt bikes, very recently announced they are closing their doors. Here’s the article I read on it: Alta Motors Ceases Operations. This is interesting on several levels. Alta previously announced a strategic partnership with Harley-Davidson. I thought this would figure into Harley’s Livewire project and help both companies enormously, but I guess that isn’t the case. Last year, Alta lowered their prices substantially. I thought this would increase their sales, even though their prices were still high. Alta had the electric dirt bike niche all to themselves, and this niche seemed to be more suited to an electric motorcycle’s range limitations. Basically, motocross racing doesn’t require extended range, making Alta’s focus appear to be a well-thought-out strategy. And finally, Alta had sold a large number of bikes, and they had orders for several hundred more (see the link above).

I guess, in the final analysis, it all comes down to profitability and cash reserves, and if you don’t have enough of either, you can’t keep going. This makes Alta the second big US e-bike effort to flop (the first being the Brammo).

We are living in interesting times, and that is especially true with respect to the e-bike world. The e-bike industry is simultaneously emerging and going through a shakeout.

The CSC City Slicker, the newest player in this arena, is already playing a significant role. The three big things Slick has going for it are its price, its quality (it’s world-class; see our earlier blog posts) and CSC’s well-earned reputation for customer service. The biggest challenges for CSC and the City Slicker, I think, will be overcoming the US aversion to Chinese products, the ongoing uncertainties in the US/China trade relationship, and redefining customer expectations.

Overcoming US aversion to Chinese products is the least of these issues, and personally, I wouldn’t waste a single second attempting to do so. I think CSC and Zongshen put that issue to bed with the RX3 (it’s a world-class machine, with quality as good as or better than any motorcycle produced anywhere in the world). To be blunt, anybody still singing songs about Chinese slave labor and low Chinese quality is too stupid and too ignorant to waste time listening to. They won’t change their minds, so expending any effort attempting to convince them otherwise is an exercise in futility. Hey, there are still people who think the earth is flat and that we faked the moon landing. Best to forget about them, thank your lucky stars you aren’t that stupid, and move on.

I think the current uncertainties in the US/China trade relationship will sort themselves out within the next several months. I think the tariff issue will either go away or have relatively insignificant effects, and I think much of what is going on now is posturing and positioning for a serious set of negotiations between our leaders. Our trading relationship with China is, to borrow a phrase, too big to fail.

So we’re down to that last issue, redefining expectations, and that will be the biggest challenge for CSC and the electric motorcycle market. There’s no question that CSC has a pricing advantage that is insurmountable, and I think when CSC announced the City Slicker it set a new reality in the US e-bike industry. I think Alta realized that and that it might have played a role in their throwing in the towel. I have to think that the folks at Zero are similarly eyeing the situation and ingesting huge amounts of Pepto-Bismol (and that’s using as charitable a phrase as I can think of). You might argue that Alta and Zero have (or had) bigger motorcycles with different missions, but that would be as shortsighted and wrong as arguing that all Chinese goods are low quality or the earth is flat. Yes, Zero motorcycles are bigger and have more capability, but that’s the world as it exists this instant. The world does not stand still, my friends. Do you think, even for one second, that the City Slicker is the only sensibly-priced e-bike that will emerge from Chongqing? Do you think that future e-bikes from China will be small and have the same limitations as do today’s e-bikes? I have been to the mountain, folks. The answer is no.

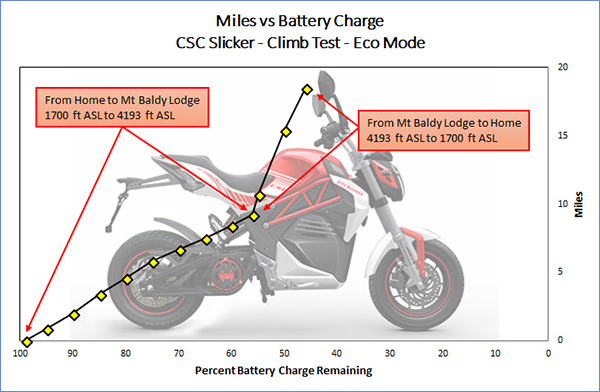

But I digress: Back to this expectations thing. The City Slicker is not a bike that you can hop on and ride 2000 miles through Baja with a few stops for gas (or topping off the battery). The range is limited to something like 40 to 60 miles today, depending on how fast you want to go. The challenge here is to reach customers willing to use their City Slickers like their iPhones…something you plug in and top off whenever you have a chance. That’s a different market than folks who buy internal combustion bikes. But it’s potentially a huge market, as I saw firsthand in China where zillions of e-bikes were tethered to extension cords in front of every business on every city street. More on this expectations thing: CSC recently announced the price for a replacement Slick battery, and I think it’s about $1100. Some of the keyboard commandos were choking on that number. Hey, go price a replacement Zero battery. You could buy three brand new City Slickers for what a Zero battery costs. Like I said earlier, the challenge is going to be redefining expectations. Are we up for it and will CSC market the City Slicker (and the Chinese e-bikes that will inevitably follow) in a manner that emphasizes this new reality?

Time will tell, but I know where I’d put my money.