By Joe Berk

I recently wrote about viewing the Triumphs and Enfields at So Cal Motorcycles in Brea, California. I included a bunch of Enfield photos with a promise to show a few Triumphs in a future blog. This is that future blog.

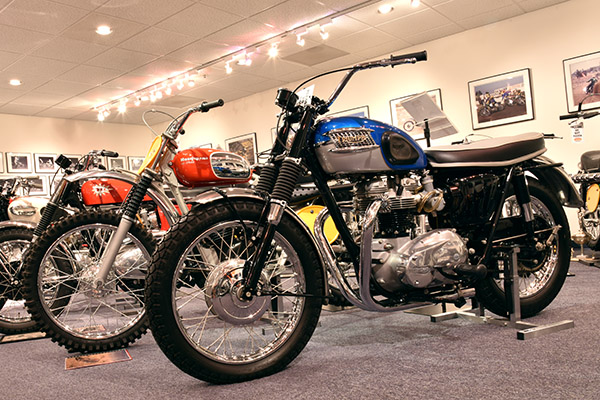

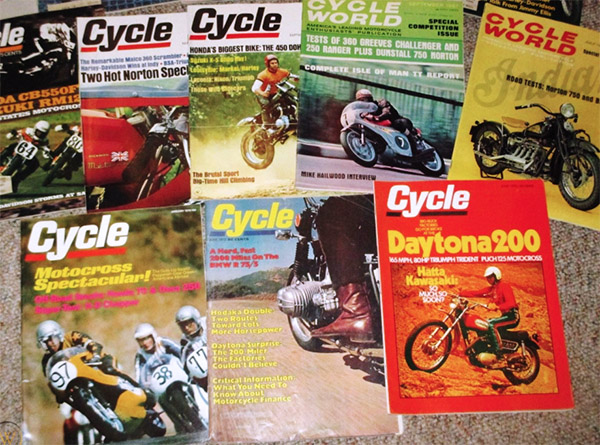

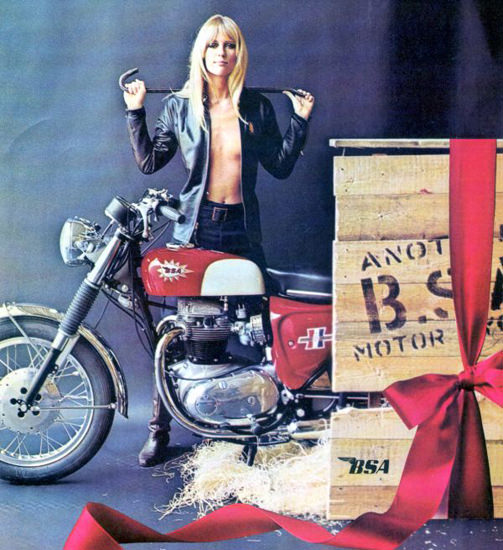

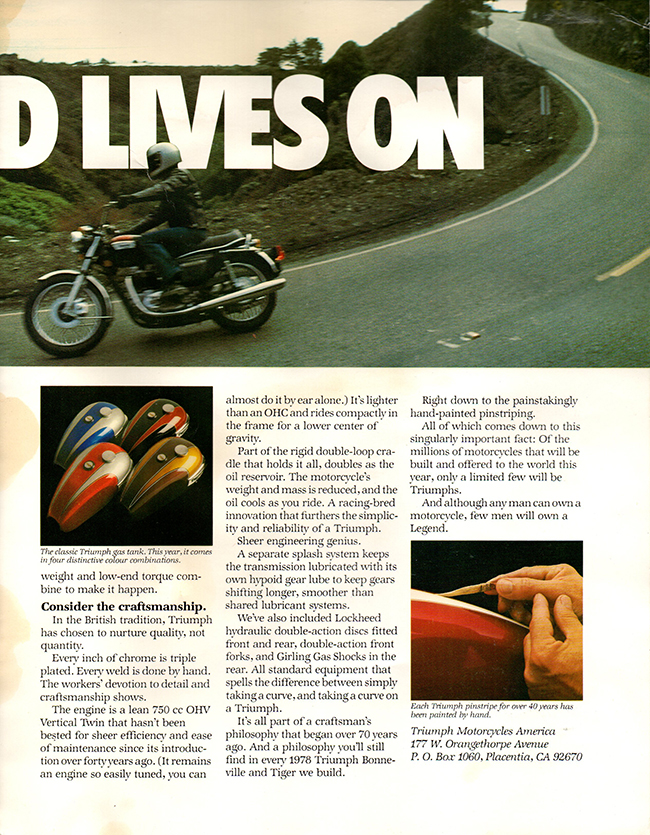

I’ve always considered myself to be a Triumph guy, even when I rode Harleys, Suzukis, CSCs, and my current Enfield. It’s a brand loyalty that goes back to my motoformative years in the 1960s. It was a lot easier then; Triumph’s models could be counted on one hand. Today, it’s confusing. I’d have to take off my shoes and socks to count them all. It’s too much for my 3-kilobyte mind, and I’m not going to cover all the Triumph models here. So Cal Triumph probably had them all in stock, though. There were a lot of motorcycles there, including a vintage Triumph Bonneville.

There were two models I wanted to see when Sue and I visited So Cal Triumph. One was the new Triumph 400 single we wrote about a few months ago; the other was Triumph’s 2500cc triple uberbike at the opposite end of the spectrum. We saw both.

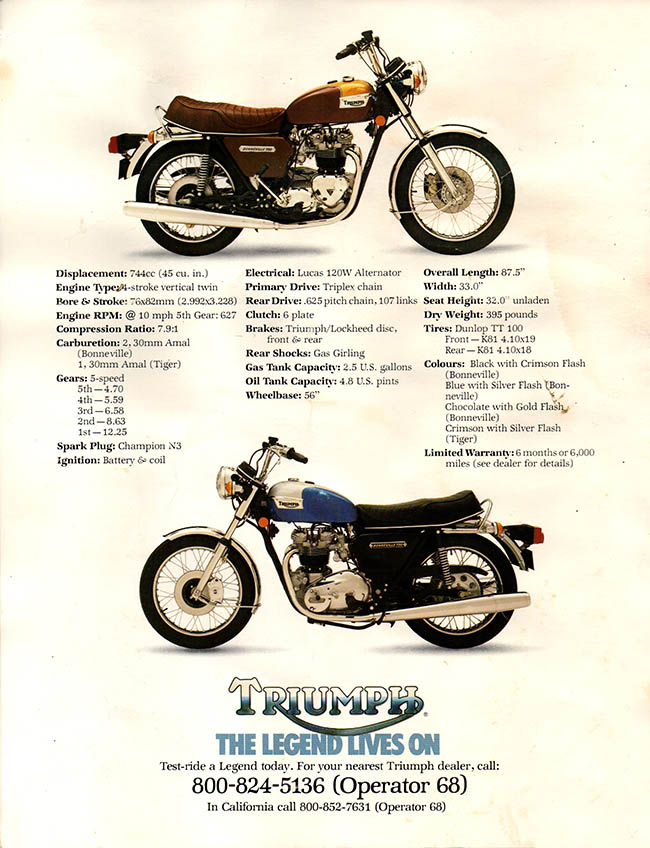

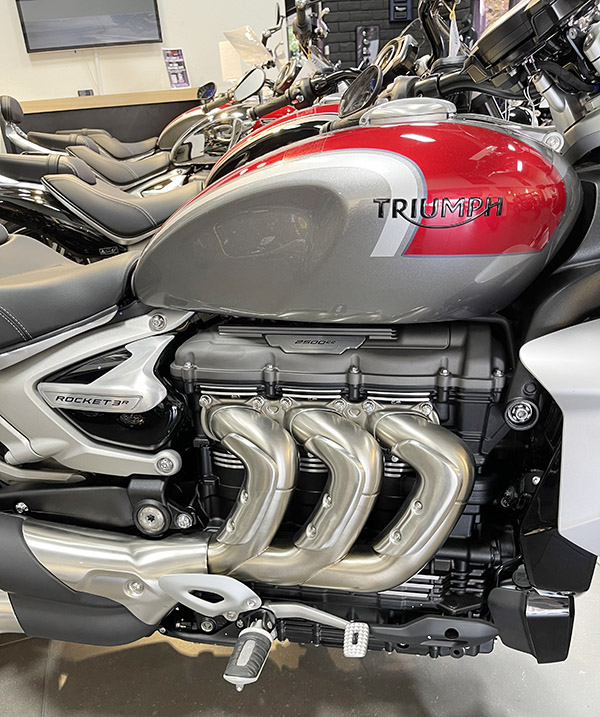

Check out the comparison photos of the vintage Bonneville’s 650cc engine and the Rocket 3 engine.

The Rocket 3 is a study in excess in all areas, including price and fuel consumption. That said, I find this motorcycle irresistible. I test rode one at Doug Douglas Motorcycles in San Bernardino when Triumph’s big triple first became available. I had a beautiful blue Triumph Tiger in those days and Doug himself let me ride the new Rocket 3. The Rocket 3 was huge then and it is huge now, but it felt surprisingly light and nimble. I don’t know how Triumph did it, but they somehow made the Rocket 3 flickable. I like it and I’d like to own one. The styling on the latest iteration makes the bike look even better.

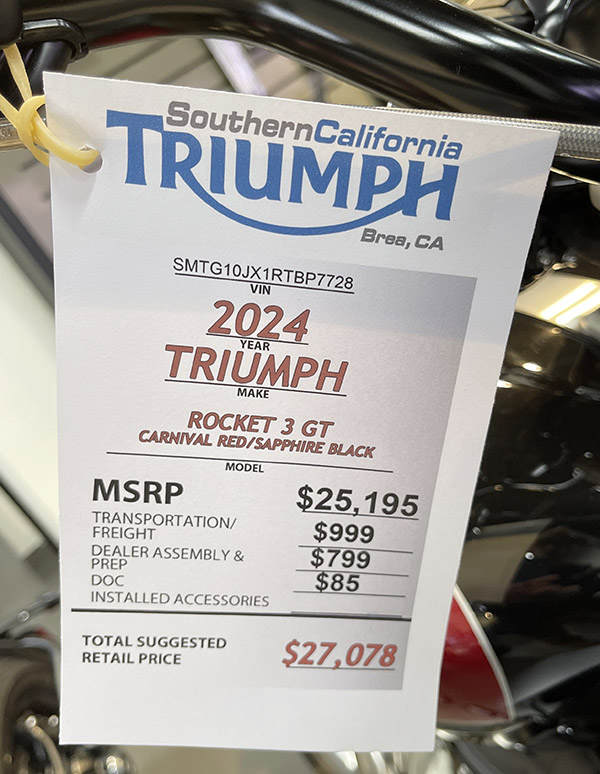

The price for this massive Triumph? Here you go:

I mentioned that there were a bunch of different Triumph models, and I suppose I should be embarrassed that I don’t know all of them like I used to. I think the problem is that I know so many things there’s only a little bit of room available for new knowledge, and I don’t want to squander that on Triumph’s extensive offerings. I know there’s the current crop of modern Bonnevilles; I don’t know all the variants thereof. But I recognize a good chrome gas tank when I see one, and I know a selfie opportunity when it presents itself.

Back to part of the objective for this blog: Seeing the new smaller Triumphs. One of these is Triumph’s dirt bike. I have no idea what the TF or the X represent (maybe the X is related to moto X, you know, as in motocross). The 250, I’m pretty sure, is the displacement. These bikes are made in the Triumph factory in Thailand (as are all models in the Bonneville line). The 250cc Triumph is not a street bike (although they made a street 250 back in the ’60s). I’d never seen the new 250 prior to my So Cal Triumph visit.

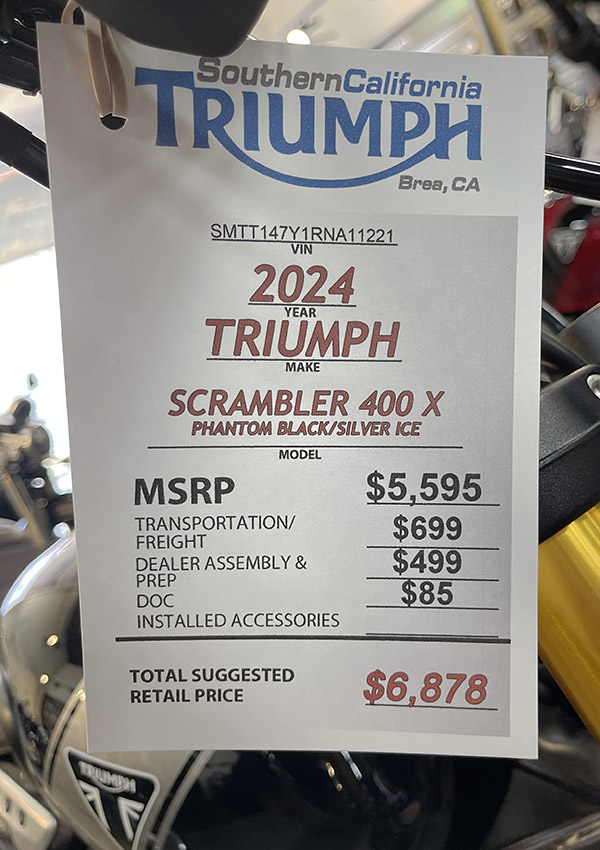

The I found what I really wanted to see: Triumph’s new 400cc singles. There are two models here: A Speed 400 (the street-oriented version), and the Scrambler 400X (another street-oriented version doing a dual sport motorcycle impersonation). The styling works for me; they both looked like what I think a Triumph should look like. We wrote about these when they were first announced; this was the first time I had seen them in person.

I asked a salesman in the Triumph showroom where these were made. He told me India (which I already knew, but I wanted to see if he would answer honestly). He then quickly added, “but they are built to Triumph quality requirements.” It was that “but…” qualifier in his comment that I found interesting. It was obviously a canned line, but for me, it was unnecessary. I have an Indian-made motorcycle (my Enfield) and I would put its quality up against any motorcycle made anywhere in the world. I suppose many folks assume that if a motorcycle is not made in Germany, Japan, Italy, or America, its quality and parts availability are going to be bad. But that’s not the case at all.

The price on the Triumph 400 Scrambler was substantially higher than the price on the Enfields I saw at So Cal Triumph. The Speed 400 was within spitting distance of the Enfield’s price, though. Are the Triumphs really better than the Enfields? I don’t know. So Cal Enfield/So Cal Triumph probably does; they see what’s going on with both bikes when they are brought in for service. That info would be interesting.

I didn’t ride either bike, mostly because I’m not in the market and I didn’t have my helmet and gloves with me. I sat on the Triumph Street 400 and it fit me well. I recognize that’s no substitute for a road test. I also recognize that a short road test is no substitute for a 1500-mile run through Baja, which is the kind of duty my motorcycles see. I like the Triumph 400cc singles and the Enfield 350cc singles. They are both right sized, good-looking motorcycles. If money didn’t matter to me and I had room in the garage, I’d buy both bikes. They both look good and their Indian-origins don’t scare me at all. If I had to pick one, it would be a tough choice.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

About that riding in Baja I mentioned above? Check this out!