After a couple of months of not being able to shoot because the creek was too high, good buddy Greg and I were finally able to get out to the range this weekend. It was sorely-needed range time, and I brought along two rifles. One was the .375 H&H Safari Grade Remington you read about a few blogs down; the other was a very nice Weatherby Mk V you haven’t heard about yet. It’s the one you see in the photo above.

This particular rifle is a bit unusual. It’s a Mk V Weatherby (Weatherby’s top of the line bolt action rifle), but it’s not chambered in a Weatherby magnum cartridge. This is one of the very few rifles Weatherby has offered over the years in a standard chambering, and in this instance, it’s the mighty .30 06 Springfield. You’ve read about the .30 06 on these pages in earlier Tales of the Gun blogs. It’s one of the all-time great cartridges and it’s my personal all-time favorite.

So, back to the Weatherby. There were four things that made this rifle particularly attractive to me when I first spotted it on the rack in a local Turner’s gun store: The stock was finished in their satin oil finish (not the typical Weatherby high gloss urethane finish), the rifle had an original 3×9 Weatherby scope, the .30 06 chambering, and the price. It checked all the boxes for me. Those early Weatherby scopes are collectible in their own right. I like an oil finished stock. And the price…wow.

The Weatherby was something I knew I had to have the instant I saw it, and (get this) it was priced at only $750. This is a rig that today, new, would sell for somewhere around $2500.

Back in 2008, when the Great Recession was going full tilt and still gaining steam, there were fabulous firearms deals to be had if you knew what you wanted and you weren’t addicted to black plastic guns. Nope, none of that black plastic silliness here. For me, it’s all about elegant walnut and blue steel. I carried a black plastic rifle for a living a few decades ago. Been there, done that, don’t need any more of it.

When I spotted the Weatherby I asked the store manager about it. She told me it was a consignment gun, and when I asked if there was any room in the price (it’s a habit; I would have paid what they were asking), she asked me to make an offer. So I did. $650 had a nice ring to it, I thought.

“Let me call the owner,” the manager said. She disappeared and returned a few minutes later. “$650 is good.” Wow. I couldn’t believe I scored like this. I felt a bit guilty and asked her if I was taking advantage of the guy who had put it on consignment, and she told me not to worry. He needed the money, I needed the rifle, and the price was good for both of us.

The Weatherby had a few minor dings in the stock and the finish was a bit worn in a few places, but the metal was perfect. Because it was an oil finished stock, it was a simple matter to steel wool it down and add a few coats of TruOil, and the Weatherby was a brand new rifle again.

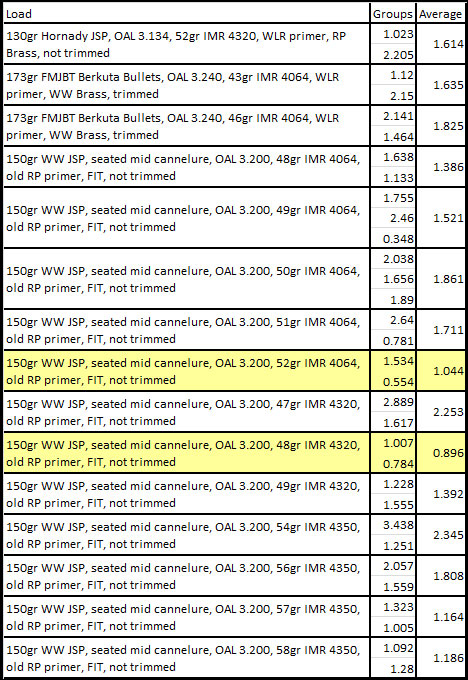

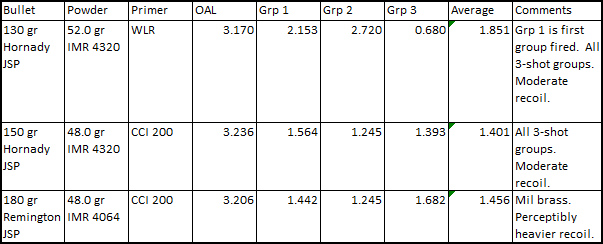

I’ve shot this rifle quite a bit over the last 10 years and I knew it shot well, but I hadn’t recorded which load shot best. I had several loads I’ve developed for other .30 06 rifles over the last few decades (like I said above, it’s my favorite), and I grabbed three that have worked well in other rifles. The good news is the Weatherby isn’t fussy. It shot all three well. The bad news is…well, there isn’t any bad news. It’s all good.

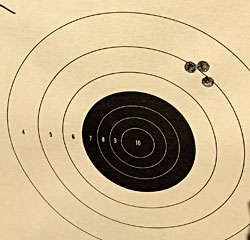

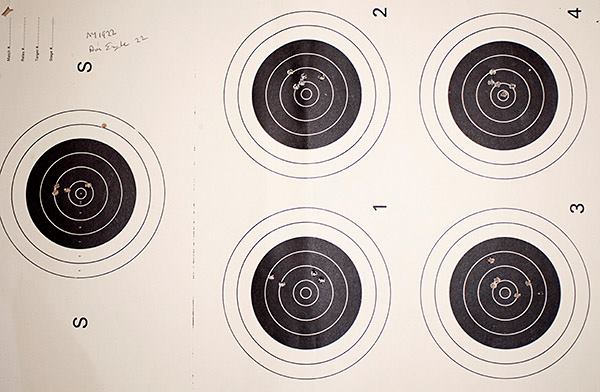

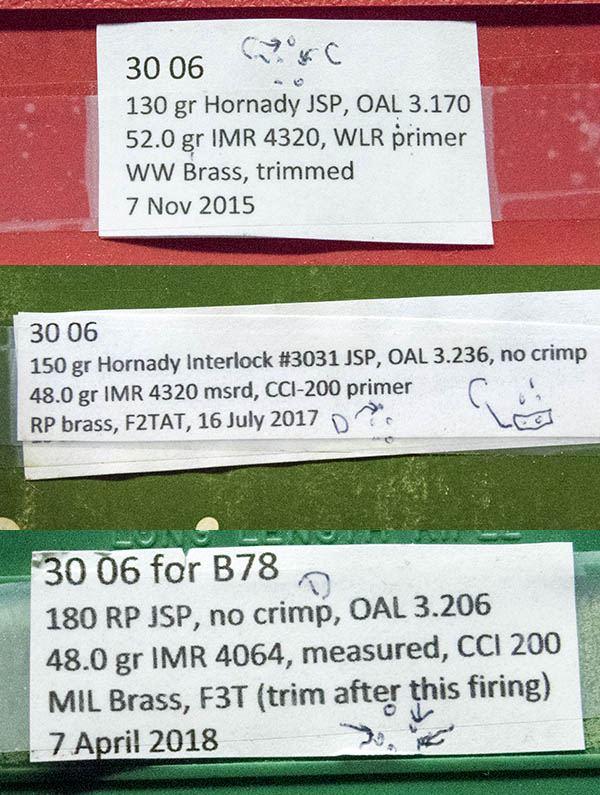

The first load is one with a lighter bullet that has worked well on Texas jackrabbits in a single-shot Ruger No. 1. I found that load back in the 1970s when I spent entirely too much time chasing rabbits in the desert east of El Paso. It’s the 130 grain jacketed soft point Hornady with a max load (52.0 grains) of IMR 4320 powder. Yeah, the first two groups were larger than I would have liked, but don’t forget that I had not been on the rifle range for a couple of months. Folks think that shooting off a rest eliminates the human element, but it does not. I was getting my sea legs back with those first two groups. It’s the third group that tells the story here, and that one was a tiny 0.680 inches. If I worked on this load a bit and shot a bit more, this is a sub-minute-of-angle rifle.

The next load is the hog load I used in a Winchester Model 70 on our Arizona boar hunt last year. That one uses a 150 grain Hornady jacketed soft point with 48.0 grains of IMR 4320 powder. It shot well in the Model 70 and it shoots well in the Weatherby, too. The Weatherby averaged 1.401 inches at 100 yards with this load. The point of impact was about 3 inches lower than the 130 grain load described above.

The third and final load I tried this weekend was with a heavier 180 grain Remington jacketed soft point bullet. I had originally developed this as the accuracy load for an older Browning B-78 single shot rifle (I’ll have to do a blog on that one of these days; it, too, has stunning wood). This is a near max load (48.0 grains of IMR 4064 propellant) and with those heavier 180 grain bullets, recoil was attention-getting. But it was still tolerable, and the average group size hung right in there with the 150 gr load. It averaged 1.456 3-shot groups at 100 yards. Like they say, that’s close enough for government work. Another cool thing…the 180 grain load point of impact was the same height above point of aim as the 130 grain load, but the group centers were about three inches to the left of center.

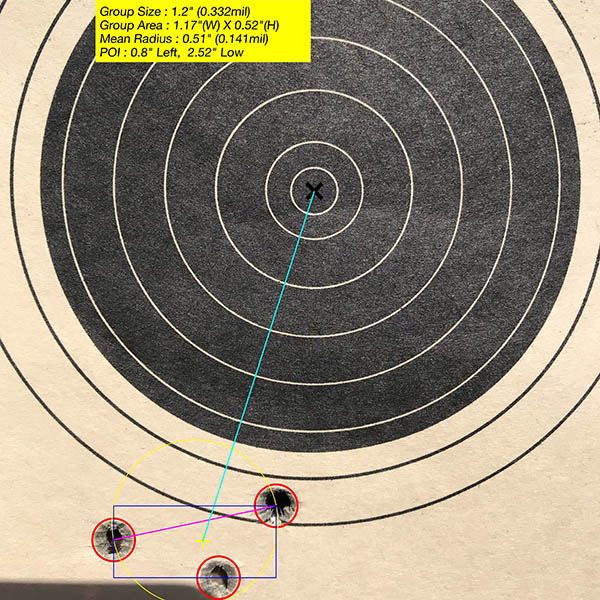

There’s one last thing I wanted to share with you before signing off today. Good buddy Greg is an accuracy chaser like me. He was out there with his rifles this weekend trying a few of his loads. When I measure group size, I always use a caliper. Greg has an app on his iPhone (it’s called SubMOA and it’s free) that allows him to simply take a photo of the target and it computes group size and a bunch of other good data. I always wondered if the results from Greg’s iPhone app were as good as the real thing, so I asked him to take photos of two of my targets and tell me what the iPhone app felt the group sizes were. He did.

So there you have it. If you’d like to read more of our Tales of the Gun Stories, you will find them here.

More good stuff:

Order targets from Amazon.

Buy RCBS reloading equipment here!

Get ammo boxes here!

Never miss an ExNotes blog: Sign up here!