Putting a motorcycle engine back together is much harder than taking it apart. Staring at the boxes of gears and cams the other day I found my memory beginning to fade, where did this spring go? I figured I better get on with the reassembly because if I waited any longer I wouldn’t remember who left their Husqvarna motorcycle in my shed. The nerve! Reluctantly, I set aside my ongoing concrete projects for a few days and began work on the Husky SMR510.

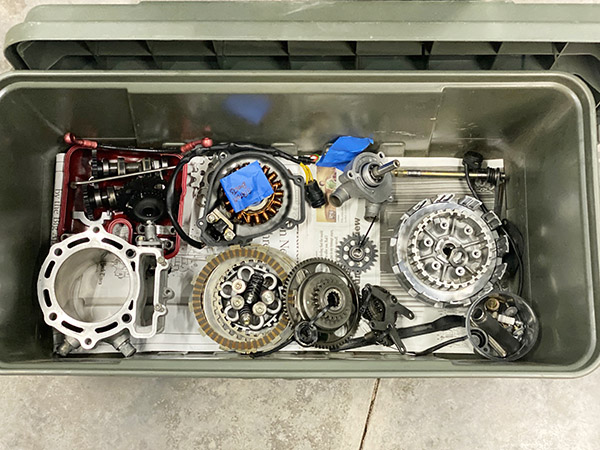

The crankcases and all internal parts were washed with mineral spirits turning the skin on my hands a nice shade of chalky white. After the mineral spirits a liberal application of Gunk engine degreaser was sprayed into all the nooks and crannies. Then a blast of good, Sunoco rainwater (filtered to 5 microns!) from the garden hose hopefully flushed out any stray bits of metal from the broken transmission. My little 18-volt Ryobi grass blower did a fair job of drying the pieces and laying the stuff out in the warm New Mexican sunshine finished the cleaning process.

Since the old transmission was the part that felled the Husqvarna and I was using a second-hand transmission, I dry fit the transmission and crankcase halves together. Once the gear shafts and shift forks were in their proper positions I spun the shift drum and is seemed like all 6 speeds were selectable.

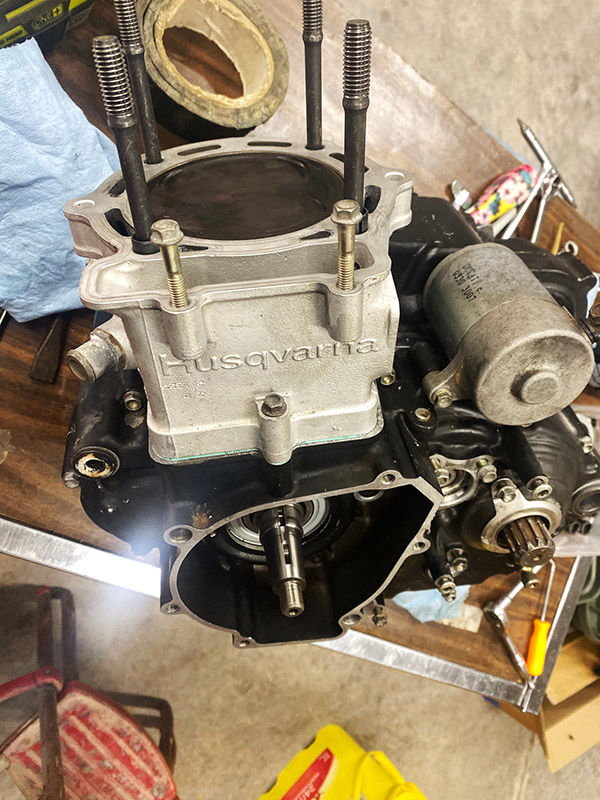

I think I mentioned in a previous episode of Grind Me A Pound Of Reverse that I didn’t like the gear spacing on the second-hand transmission. The gears didn’t quite line up right. They were offset a couple thousandths of an inch to my eye. Anyway, I went ahead and gooped up the cases with Yamabond4 and with the crankshaft, balancer shaft and gearbox in place, slid the two cases together. They went together easily. Of course nothing is ever really easy, now is it?

I tried to spin the clutch shaft and the transmission was bound up tighter than a (sexual innuendo of your choice). Quickly, before the Yamabond4 had a chance to set I took the cases back apart and cleaned all the goop off the sealing surfaces. This situation needed more study, more than I was willing to give at the time so I gave up and went outside to dig a hole.

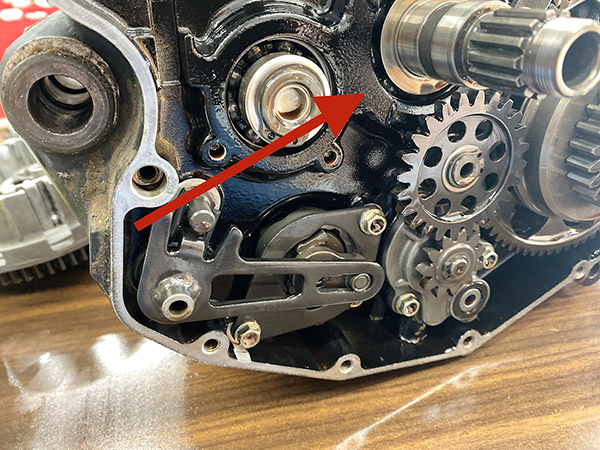

The next day I took a look at photos I had made during disassembly. I saw a spacer under the clutch basket and knew this same spacer was now inside the transmission. Turns out I had this spacer on the wrong side of the clutch shaft. This was also why the gears didn’t line up quite right. After relocating the spacer to outboard of the cases and reassembling the transmission, shift forks and then re-gooping the cases and tightening up the mess everything spun freely. This is what I mean by memory fading.

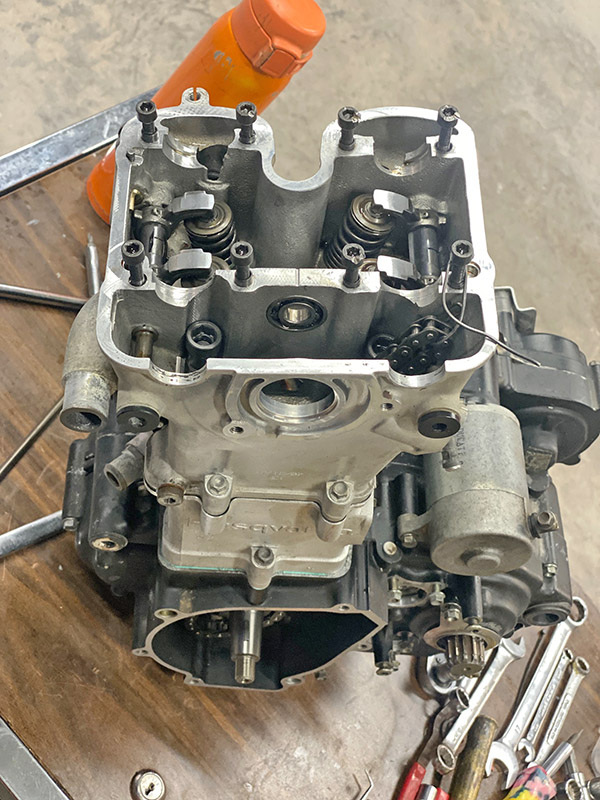

While its transmission might be fragile the Husqvarna has a well-engineered engine. Everything that spins rides on ball bearings; even the shift lever rides on needle bearings. This engine could run without oil for longer than you’d think. At 20,000 miles the valve train showed little wear, the cams were unmarred and the cam chain tensioners were in like-new condition. The whole layout is fairly simple and logical.

The big piston slips into a sleeveless aluminum cylinder bore coated with some sort of magic stuff that still showed hone marks. One area of concern is the base gasket. The gasket set I bought had a paper base gasket and the original was metal. From my experience the SMR510 engine has a lot of crankcase pressure. Hopefully the paper gasket works.

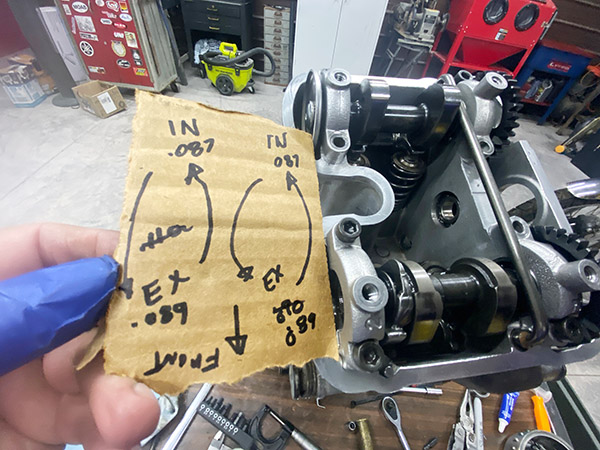

Installing the cylinder head was uneventful; the kit gasket looked like the same metal-sandwich material as the factory gasket. While I had the engine on the bench I checked the valve clearances. They wanted a bit of adjustment and in an amazing stroke of luck swapping the exhaust shims to the intake valves and the intake valve shims to the exhaust brought everything into spec. The fact that both left and right exhaust shims and both left and right intake shims were the same thickness speaks to even wear, careful machining and accurate valve installed-height during factory assembly.

There are a million bits to strapping the engine back into the frame. I put mostly new water hoses on because the kit I bought was missing a few. Since the swing arm was off I dismantled the rising-rate suspension linkage and greased the needle bearings. The forks on the Husky don’t turn sharp at all. To get a bit more steering angle I shortened the fork stops in an attempt to get an inch or two less turning radius. The fork tubes just kiss the plastic gas tank now so I’m maxed out. All in, it took the better part of a day to finish the engine install.

Starting the bike produced a few pops and farts until the fuel injection bled itself out and then the bike fired up! I leaned the Husky onto the side stand, lifting the rear wheel off the ground and ran through the transmission. All 6 gears were present and accounted for.

A quick test ride confirmed that even a stopped clock is right twice a day: I managed to get it back together and the bike runs just like before. Almost. The valve cover gasket is leaking so I’ll have to take a look at that. Total cost for the repair was around $400. My time, of course, was free. That’s $5600 less than a new Suzuki DR650, which was my Plan A when the Husky spit up its guts.

I think the reason for the Husqvarna transmission failing in the first place goes back to the SMR’s roots of being a dirt bike converted to street use. In the conversion process Husky’s engineers failed to put any kind of cushion in the drive train. You don’t really need cushion in the dirt because dirt is never all that grippy.

The crankshaft has a straight-cut gear to the clutch basket, the solid clutch basket has no cushioning springs, and then it’s direct to the transmission gears, to the countershaft sprocket and on to the rear wheel where there are no rubber cushions. The sprocket bolts solidly to the rear hub. Think about that big 500cc piston pounding the gearbox while the bike is on asphalt. The only give in the entire system is the rubber of the rear tire.

Maybe Berk is right: Maybe I just don’t know how to ride a 500cc single. (Note from Berk: I said that?) Seeing how the Husqvarna is built will change my riding style. I’ll let the engine rev a bit more and not lug the thing down to rattle on the gears. I’ll also try to stay on dirt roads whenever possible. Or, maybe it was a fluke. Only time and miles will tell.

Please keep hitting the popup ads!

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

More Resurrections!

Most excellent blog , Joe!

Congrats on the rebuild!

Nice job. There’s pleasure to be had keeping a motorcycle out of the scrapyard. And easy acceleration and no burnouts on the asphalt isn’t as awful as it sounds. I wonder if there’s a rear wheel containing a cush-drive that would fit the Husky. I’ll bet there is. Maybe one from the Suzuki dr-400cc dual sport? Nope, not that one, I just checked.