By Joe Berk

1500: Keep that number in mind. I’ll tell you what it means at the end of this post.

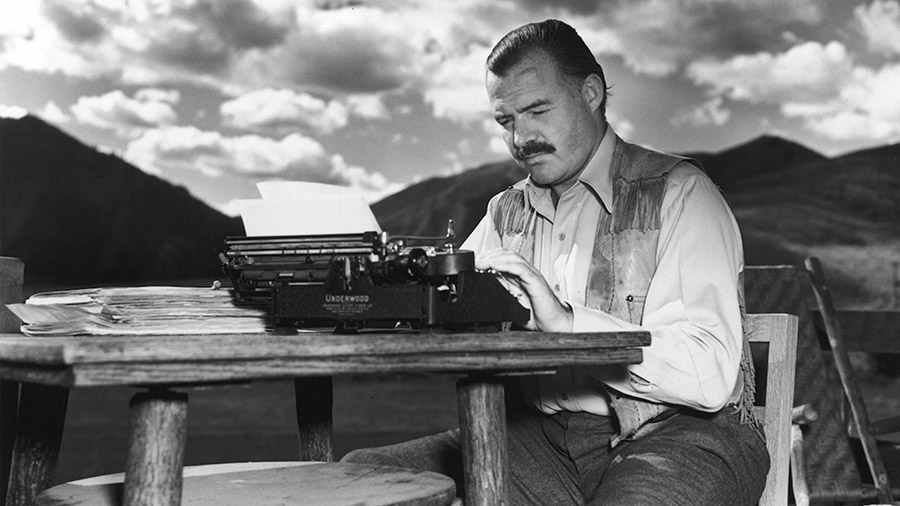

As I mentioned in the introductory blog on our ExNotes Idaho expedition, I was surprised to learn of the apparently well-known strong connection between Idaho and Ernest Hemingway. My previous ignorance of this connection made me feel kind of illiterate when I read about it at the Basque Museum, and then again in Picabo while we were driving to Craters of the Moon National Monument. I wouldn’t want any of our readers to feel my pain, so I thought I would offer a brief Hemingway biography and explain how the Idaho/Hemingway connection developed.

I previously wrote about the Basque Museum a blog or two back. Our next adventure was Craters of the Moon, and on our way there as we passed through the small town of Picabo I thought I would top off the Jeep and grab a cup of coffee. The gas station had a small general store and a restaurant, so Susie and I grabbed lunch. The place had an interesting corner devoted to Ernest Hemingway and his Idaho adventures.

Hemingway loved hunting and fishing in the Silver Creek area near Picabo with Bud Purdy, a local rancher and Idaho legend. Purdy was an interesting man, too. You can read about him here.

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born in Oak Park, Illinois (a small town near Chicago) on July 21, 1899. He was wounded in World War I, he went on to become one of the world’s great novelists, he married four times, and he died at age 61 in Ketchum, Idaho. But there’s a lot more to the Hemingway story than just those two short sentences.

As a young man growing up in what was then a predominately rural area, Hemingway’s father introduced him to hunting and fishing. He graduated from the Oak Park public school system in 1917 and went to work as a reporter at the Kansas City Star. It’s been said that’s where he developed his writing style, based on the newspaper’s guidelines emphasizing short sentences and paragraphs, writing in the active style, shortness, and clarity. Hemingway carried the style to his fiction, later explaining “Those were the best rules I ever learned for the business of writing. I’ve never forgotten them.”

When World War I started, Hemingway wanted to serve but poor eyesight prevented his enlisting. He instead volunteered to be a Red Cross ambulance driver in Italy. Hemingway was wounded only a month into this adventure by a mortar round, and then wounded again immediately after that by machine gun fire. All this occurred while carrying a wounded soldier to safety. The Italian government awarded Hemingway their Silver Medal for Valor.

Hemingway returned home and went to work for the Toronto Star Weekly, where he married his first of four wives in 1921. The Hemingways moved to Paris, where he met several of the great authors of the era while still working as a reporter covering such things as the Geneva Conference, bullfighting, and fishing. It was while Hemingway was in Paris that his first works of fiction were published, including Indian Camp and Cross Country Snow.

From 1925 to 1929, Hemingway wrote some of the world’s great literary masterpieces, including Our Time in 1925. It contained The Big Two-Hearted River, The Sun Also Rises, and Men Without Women. A Farewell to Arms followed in 1929, which was quickly recognized as a defining World War I masterpiece and earned Hemingway a reputation as a literary giant. Hemingway became a world traveler, visiting Key West for fishing, Africa for hunting, and Spain for bullfighting. He continued writing, creating For Whom the Bell Tolls, Death in the Afternoon, and The Green Hills of Africa.

For a time in the pre-Castro days, Hemingway lived in Cuba. Hemingway lost his home when Fidel Castro confiscated private property in 1958. He and his fourth wife bought a home in Ketchum, Idaho, where he would live out the rest of his life.

Hemingway had spent time in Idaho prior to purchasing his Ketchum home. Averill Harriman (an American entrepreneur who owned the Union Pacific Railroad and other businesses) was promoting a new resort in Sun Valley, Idaho. In 1939 Harriman invited Hemingway to visit the Sun Valley Lodge and that set the hook. Hemingway hunted and fished Idaho, and he fell in love with the area. Hemingway wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls in Room 206 of the Sun Valley Lodge (known today as the Hemingway Suite). While a guest at the Sun Valley Lodge, Hemingway also wrote Islands in the Stream, The Garden of Eden, and A Moveable Feast.

Later in life, Hemingway struggled with poor health and depression. Some say he was an alcoholic. He had experienced numerous concussions, a couple of car accidents, and two airplane crashes. Hemingway committed suicide by shooting himself in his Ketchum home in July of 1961 at the age of 61.

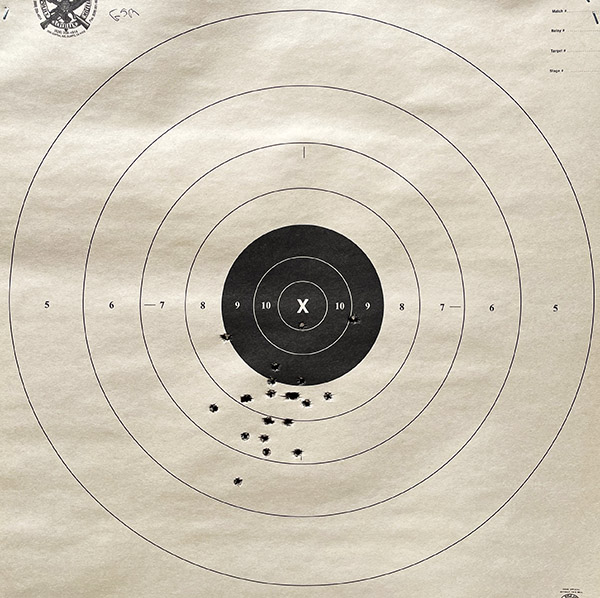

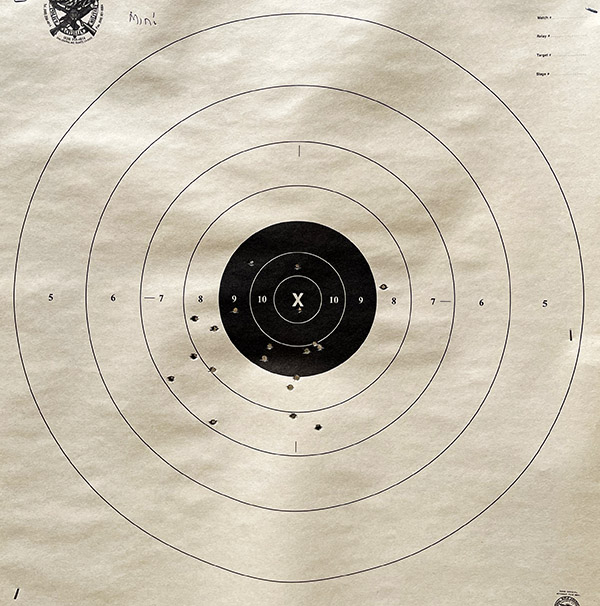

Ernest Hemingway was an outdoorsman, a shooter, and a hunter. In other words, he was my kind of guy, so it’s surprising that the only Hemingway novel I ever read was The Old Man and the Sea. That’s a character defect I aim to correct in the near future.

It’s probably appropriate that this post is about Ernest Hemingway, as this is our 1500th literary endeavor on the ExhaustNotes blog. Yep, 1500 posts! We appreciate you reading our blog, we appreciate your comments, and we especially appreciate you clicking on those pesky popup ads!

Never miss an ExNotes blog: