By Joe Berk

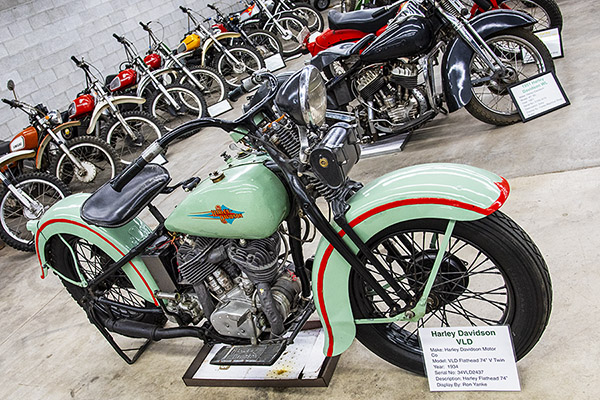

I love Idaho and the Boise area, and no story about this part of the country would be complete without mentioning at least one of the motorcycle rides out of town. A short and easy one is the run along Idaho Highway 21 to Lucky Peak State Park.

It’s easy: Just grab Interstate 84 east out of Boise and then Highway 21 north. You’ll be running alongside the Boise River up to Lucky Peak. It only takes about 10 minutes to get up to Luck Peak State Park if you are in a car or on a motorcycle. If you’re into bicycling (I am), it’s about a 30-minute ride on the Boise River Greenbelt, a dedicated bike lane that parallels Highway 21 along the river. The bike lane is protected from traffic by a concrete barrier. I didn’t have a bicycle on this Boise trip, but I found myself wishing I did. It looked like a great bicycle ride.

Highway 21’s north and south lanes are separated, and the northbound lanes up to Lucky Peak State Park don’t have good places to pull off and grab photos. For that reason, most of my on=the-road pictures were taken on our ride back to Boise, including this one of a sign for the Diversion Dam.

You get a great look at the Boise River’s Diversion Dam heading to Lucky Peak, but like I said above, there’s no place to pull off for a photo. On the way back, you see the sign in the above photo, but you can’t see the Dam from there. It provides water for Idaho’s agricultural canal system and it also generates electricity. The company that built it in 1909 took a financial bath on the project, but the dam didn’t give a damn. It’s well over a hundred years old and it’s been doing its job well the entire time.

The Lucky Peak State Park is a multi-use park. You can swim in its freshwater beach, there are a couple of boat launch ramps, we met people there for kayaking, you can rent watercraft, you can fish, or you can just hang out and take pictures (which is what we did).

There are two dams in this area. The first is the Diversion Dam mentioned above; the second is a much larger Army Corps of Engineers Dam that forms Lucky Peak Lake.

The ride back had places along Highway 21 to pull over and grab a photo or two, which is what we did. There’s a lot to see and do in the Boise area and in Idaho, and there’s more coming up here on ExNotes about that. Stay tuned, my friends.

Never miss an ExNotes blog: