This was a blog I wrote for CSC about 6 years ago, and it’s still relevant. Earlier this year I posted a photo showing my Harley in Baja and Gresh made a good comment: Any motorcycle you take a trip on is an adventure motorcycle. I agree with that. The earlier blogs on my Harley Softail had me thinking about this question again: What is the perfect motorcycle?

Cruisers. Standards. Sports bikes. Dirt bikes. Dual sports. Big bikes. Small bikes. Whoa, I’m getting dizzy just listing these.

The Good Old Days

In the old days, it was simple. There were motorcycles. Just plain motorcycles. You wanted to ride, you bought a motorcycle. And they were small, mostly. I started on a 90cc Honda (that’s me in that photo to the right). We’d call it a standard today, if such a thing still existed.

In the old days, it was simple. There were motorcycles. Just plain motorcycles. You wanted to ride, you bought a motorcycle. And they were small, mostly. I started on a 90cc Honda (that’s me in that photo to the right). We’d call it a standard today, if such a thing still existed.

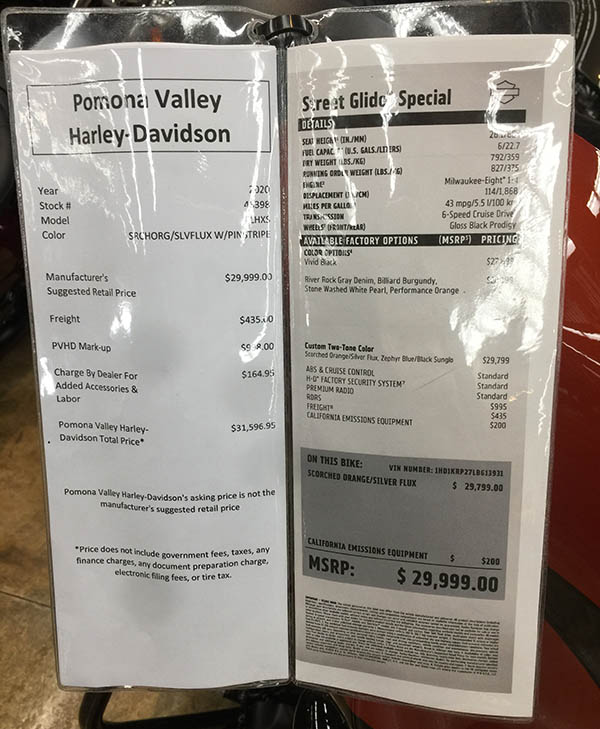

Then it got confusing. Bikes got bigger. Stupidly so, in my opinion. In my youth, a 650 was a huge motorcycle, and the streets were ruled by bikes like the Triumph Bonneville and the BSA Lightning. Today, a 650 would be considered small. The biggest Triumph today has a 2300cc engine. I don’t follow the Harley thing anymore, but I think their engines are nearly that big, too. The bikes weigh close to half a ton. Half a ton!

I’ve gone through an evolution of sorts on this topic. Started on standards, migrated into cruisers after a long lapse, went to the rice rockets, then morphed into dual sports.

Cruisers and Adventure Bikes

The ADV bug hit me hard about 15 years ago. I’d been riding in Baja a lot and my forays occasionally took me off road. Like many folks who drifted back into motorcycles in the early 1990s, the uptick in Harley quality bit me. As many of us did, I bought my obligatory yuppie bike (the Heritage Softail) and the accompanying zillion t-shirts (one from every Harley dealer along the path of every trip I ever took). I had everything that went along with this kind of riding except the tattoo (my wife and a modicum of clear thinking on my part drew the line there). Leather fringe, the beanie helmet, complimentary HOG membership, and the pot belly. I was fully engaged.

Unlike a lot of yuppie riders of that era, though, I wasn’t content to squander my bucks on chrome, leather fringe, and the “ride to live, live to ride” schlock. I wanted to ride, and ride I did. All over the southwestern US and deep into Mexico. Those rides were what convinced me that maybe an 800+ lb cruiser was not the best bike in the world for serious riding…

The Harley had a low center of gravity, and I liked that. It was low to the ground, and I didn’t like that. And it was heavy. When that puppy started to drift in the sand, I just hung on and hoped for the best. Someone was looking out for me, because in all of that offroading down there in Baja, I never once dropped it. As I sit here typing this, enjoying a nice hot cup of coffee that Susie just made for me, I realize that’s kind of amazing.

The Harley had a low center of gravity, and I liked that. It was low to the ground, and I didn’t like that. And it was heavy. When that puppy started to drift in the sand, I just hung on and hoped for the best. Someone was looking out for me, because in all of that offroading down there in Baja, I never once dropped it. As I sit here typing this, enjoying a nice hot cup of coffee that Susie just made for me, I realize that’s kind of amazing.

The other thing I didn’t like about the Harley was that I couldn’t carry too much stuff on it without converting that bike into a sort of rolling bungee cord advertisement. The bike’s leather bags didn’t hold very much, the Harley’s vibration required that I constantly watch and tighten their mounting hardware, and the whole arrangement really wasn’t a good setup for what I was doing. The leather bags looked cool, but that was it. It was bungee cords and spare bags to the rescue on those trips…

Sports Bikes

The next phase for me involved sports bikes. They were all the rage in the early 90s and beyond, but to me they basically represent the triumph of marketing hoopla over common sense. I bought a Suzuki TL1000S (fastest bike I ever owned), and I toured Baja with it. It would be hard to find a worse bike for that kind of riding. The whole sports bike thing, in my opinion, was and is stupid. You sit in this ridiculous crouched over, head down position, and if you do any kind of riding at all, by the end of the day your wrists, shoulders, and neck are on fire. My luggage carrying capacity was restricted to a small tankbag and a ridiculous-looking tailbag.

I was pretty hooked on the look, though, and I went through a succession of sports bikes, including the TL1000S, a really racy Triumph Daytona 1200 (rode that one from Mexico to Canada), and a Triumph Speed Triple. Fast, but really dumb as touring solutions, and even dumber for any kind of off road excursion.

I was pretty hooked on the look, though, and I went through a succession of sports bikes, including the TL1000S, a really racy Triumph Daytona 1200 (rode that one from Mexico to Canada), and a Triumph Speed Triple. Fast, but really dumb as touring solutions, and even dumber for any kind of off road excursion.

Phase III for me, after going through the Harley “ride to live” hoopla and the Ricky Racer phases, was ADV riding and dual sport bikes. The idea here is that the bike is equally at home on the street or in the dirt. Dual purpose…dual sport. I liked the idea, and I thought it would be a winner for my kind of riding.

A BMW GS versus Triumph’s Tiger

The flavor of the month back then was the BMW GS. I could never see myself on a Beemer, but I liked the concept. I was a Triumph man back in those days, and the Triumph Tiger really had my attention. A couple of my friends were riding the big BMW GS, but I knew I didn’t want a Beemer. In my opinion, those bikes are overpriced. The Beemers are heavy (over 600 lbs on the road), they have a terrible reputation for reliability, and I think they looked goofy. The Tiger seemed to be a better deal than the Beemer, and it sure had the right offroad look. Tall, an upright seating position (I had enough of that sports bike nonsense), and integrated luggage. So, I bit the bullet and shelled out something north of $10K back in ’06 for this beauty…

The Triumph had a few things going for it…I liked the detachable luggage, it was fast, it got good gas mileage (I could go 200+ miles between gas stations), and did I mention it was fast?

The Triumph had a few things going for it…I liked the detachable luggage, it was fast, it got good gas mileage (I could go 200+ miles between gas stations), and did I mention it was fast?

The Tiger’s Shortfalls

Looks can be deceiving, though, and that Tiger was anything but an off-road bike. It was still well over 600 lbs on the road with a full tank of gas, and in the soft stuff, it was terrifying. I never dropped the Triumph, but I sure came close one time. On a ride out to the Old Mill in Baja (a really cool old hotel right on the coast a couple hundred miles south of the border), the soft sand was bad. Really bad. Getting to the Old Mill involved riding through about 5 miles of soft sand, and it scared the stuffing out of me. I literally tossed and turned all night worrying about the ride out the next morning. It’s not supposed to be like that, folks.

And the Tiger was tall. Too tall, in my opinion. I think all of the current dual sport bikes are too tall. I guess the manufacturers do that because their marketing studies show a lot of basketball players buy dual sports. Me? I don’t play basketball and I never cared for a seat that high. Just getting on the Tiger was scary. After throwing my leg over the seat, I’d fight to lean the bike upright, and not being able to touch the ground on the right side until I had the thing upright was downright unnerving. I never got over that initial “getting on the bike” uneasiness. What were those engineers thinking?

The other thing that surprised me about the Tiger was that it was uncomfortable. The seat was hard (not comfortably hard, like a well designed seat should be, but more like sitting on small beer keg), and the foot pegs were way too high. I think they did that foot peg thing to make the bike lean over more, but all it did for me was make me feel like I was squatting all day. Not a good idea.

Kawasaki’s KLR 650

I rode the Tiger for a few years and then sold it. Even before I sold it, though, I had bought a new KLR 650 Kawasaki. It was a big step down in the power department (I think it has something like 34 or 38 horsepower), but I had been looking at the KLR for years. It seemed to be right…something that was smaller, had a comfortable riding position, and was reasonably priced (back then, anyway).

I had wanted a KLR for a long time, but nobody was willing to let me ride one. That’s a common problem with Japanese motorcycle dealers. And folks, this boy ain’t shelling out anything without a test ride first. I understand why they do it (they probably see 10,000 squids who want a test ride for every serious buyer who walks into a showroom), but I’m old fashioned and crotchety. I won’t buy anything without a test ride. This no-test-ride thing kept me from pulling the trigger on a KLR for years. When I finally found a dealer who was willing to let me ride one (thank you, Art Wood), I wrote the check and got on the road…and the off road…

My buddy John and I have covered a lot of miles on our KLRs through Baja and elsewhere. I still have my KLR, but truth be told, I only fire it up three or four times a year. It’s a big bike. Kawi says the KLR is under 400 lbs, but with a full tank of gas on a certified scale, that thing is actually north of 500 lbs. I was shocked when I saw that on the digital readout. And, like all of the dual sports, the KLR is tall. It still gives me the same tip-over anxiety as the Tiger did when I get on it. And I know if I ever dropped it, I’d need a crew to get it back on its feet.

My buddy John and I have covered a lot of miles on our KLRs through Baja and elsewhere. I still have my KLR, but truth be told, I only fire it up three or four times a year. It’s a big bike. Kawi says the KLR is under 400 lbs, but with a full tank of gas on a certified scale, that thing is actually north of 500 lbs. I was shocked when I saw that on the digital readout. And, like all of the dual sports, the KLR is tall. It still gives me the same tip-over anxiety as the Tiger did when I get on it. And I know if I ever dropped it, I’d need a crew to get it back on its feet.

That thing about dropping a bike is a real consideration. I’ve been lucky and I haven’t dropped a bike very often. But it can happen, and when it does, it would be nice to just be able to pick the bike up.

Muddy Baja

On one of our Baja trips, we had to ride through a puddle that looked more like a small version of Lake Michigan. I got through it, but it was luck, not talent. My buddy Dave was not so lucky…he dropped his pristine Yamaha mid-puddle…

The fall broke the windshield and was probably a bit humiliating for Dave, but the worst part was trying to lift the Yamaha after it went down. Slippery, muddy, wet…knee deep in a Mexican mudbath. Yecchh! It took three of us to get the thing upright and we fell down several times while doing so. Thinking back on it now, we probably looked pretty funny. If we had made a video of it, it probably would have gone viral.

The fall broke the windshield and was probably a bit humiliating for Dave, but the worst part was trying to lift the Yamaha after it went down. Slippery, muddy, wet…knee deep in a Mexican mudbath. Yecchh! It took three of us to get the thing upright and we fell down several times while doing so. Thinking back on it now, we probably looked pretty funny. If we had made a video of it, it probably would have gone viral.

The Perfect Bike: A Specification

So, where is this going…and what would my definition of the perfect touring/dual sport/ADV bike be?

Here’s what I’d like to see:

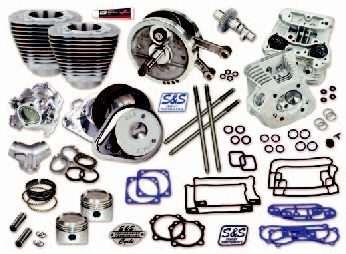

Something with a 250cc to 500cc single-cylinder engine. My experience with small bikes as a teenager and my more recent experience has convinced me that this is probably the perfect engine size. Big engines mean big bikes, and that kind of gets away from what a motorcycle should be all about. Water cooled would be even better. The Kawi KLR is water cooled, and I like that.

A dual sport style, with a comfortable riding position. No more silly road racing stuff. I’m a grown man, and when I ride, I like to ride hundreds of miles a day. I want my bike to have a riding position that will let me do that.

A windshield. It doesn’t have to be big…just something that will flip the wind over my helmet. The Kawi and the Triumph got it right in that department.

Integrated luggage. The Triumph Tiger got that part right. The KLR, not so much.

Light weight. Folks, it’s a motorcycle…not half a car. Something under 400 lbs works for me. If it gets stuck, I want to be able to pull it out of a puddle. If it drops, I want to be able to pick it up without a hoist or a road crew. None of the current crop of big road bikes meets this requirement.

Something that looks right and is comfortable. I liked the Triumph’s looks. But I want it to be comfortable.

Something under $5K. Again, it’s a motorcycle, not a car. My days of dropping $10K or so on a motorcycle are over. I’ve got the money, but I’ve also got the life experiences that tell me I don’t need to spend stupidly to have fun.

It was maybe a year after that blog that the RX3 came on the scene, and it answered the mail nicely. A year or two after the RX3 hit the scene, BMW, Kawasaki, and one or two others introduced smaller ADV motorcycles. I commented that these guys were copying Zongshen. One snotty newspaper writer told me I was delusional if I thought BMW, Kawi, and others copied Zongshen. I think that’s exactly what happened, but I don’t think they did as good a job as Zongshen did.

If you’ve got an opinion, please leave a comment. We’d love to hear from you!

Never miss an ExhaustNotes blog! Sign up here…

In the old days, it was simple. There were motorcycles. Just plain motorcycles. You wanted to ride, you bought a motorcycle. And they were small, mostly. I started on a 90cc Honda (that’s me in that photo to the right). We’d call it a standard today, if such a thing still existed.

In the old days, it was simple. There were motorcycles. Just plain motorcycles. You wanted to ride, you bought a motorcycle. And they were small, mostly. I started on a 90cc Honda (that’s me in that photo to the right). We’d call it a standard today, if such a thing still existed. The Harley had a low center of gravity, and I liked that. It was low to the ground, and I didn’t like that. And it was heavy. When that puppy started to drift in the sand, I just hung on and hoped for the best. Someone was looking out for me, because in all of that offroading down there in Baja, I never once dropped it. As I sit here typing this, enjoying a nice hot cup of coffee that Susie just made for me, I realize that’s kind of amazing.

The Harley had a low center of gravity, and I liked that. It was low to the ground, and I didn’t like that. And it was heavy. When that puppy started to drift in the sand, I just hung on and hoped for the best. Someone was looking out for me, because in all of that offroading down there in Baja, I never once dropped it. As I sit here typing this, enjoying a nice hot cup of coffee that Susie just made for me, I realize that’s kind of amazing.

I was pretty hooked on the look, though, and I went through a succession of sports bikes, including the TL1000S, a really racy Triumph Daytona 1200 (rode that one from Mexico to Canada), and a Triumph Speed Triple. Fast, but really dumb as touring solutions, and even dumber for any kind of off road excursion.

I was pretty hooked on the look, though, and I went through a succession of sports bikes, including the TL1000S, a really racy Triumph Daytona 1200 (rode that one from Mexico to Canada), and a Triumph Speed Triple. Fast, but really dumb as touring solutions, and even dumber for any kind of off road excursion. The Triumph had a few things going for it…I liked the detachable luggage, it was fast, it got good gas mileage (I could go 200+ miles between gas stations), and did I mention it was fast?

The Triumph had a few things going for it…I liked the detachable luggage, it was fast, it got good gas mileage (I could go 200+ miles between gas stations), and did I mention it was fast? My buddy John and I have covered a lot of miles on our KLRs through Baja and elsewhere. I still have my KLR, but truth be told, I only fire it up three or four times a year. It’s a big bike. Kawi says the KLR is under 400 lbs, but with a full tank of gas on a certified scale, that thing is actually north of 500 lbs. I was shocked when I saw that on the digital readout. And, like all of the dual sports, the KLR is tall. It still gives me the same tip-over anxiety as the Tiger did when I get on it. And I know if I ever dropped it, I’d need a crew to get it back on its feet.

My buddy John and I have covered a lot of miles on our KLRs through Baja and elsewhere. I still have my KLR, but truth be told, I only fire it up three or four times a year. It’s a big bike. Kawi says the KLR is under 400 lbs, but with a full tank of gas on a certified scale, that thing is actually north of 500 lbs. I was shocked when I saw that on the digital readout. And, like all of the dual sports, the KLR is tall. It still gives me the same tip-over anxiety as the Tiger did when I get on it. And I know if I ever dropped it, I’d need a crew to get it back on its feet. The fall broke the windshield and was probably a bit humiliating for Dave, but the worst part was trying to lift the Yamaha after it went down. Slippery, muddy, wet…knee deep in a Mexican mudbath. Yecchh! It took three of us to get the thing upright and we fell down several times while doing so. Thinking back on it now, we probably looked pretty funny. If we had made a video of it, it probably would have gone viral.

The fall broke the windshield and was probably a bit humiliating for Dave, but the worst part was trying to lift the Yamaha after it went down. Slippery, muddy, wet…knee deep in a Mexican mudbath. Yecchh! It took three of us to get the thing upright and we fell down several times while doing so. Thinking back on it now, we probably looked pretty funny. If we had made a video of it, it probably would have gone viral.