By Joe Berk

If you can find a copy of this weekend’s Wall Street Journal, there’s an outstanding article in the “Off Duty” section on the New Jersey Pine Barrens. We blogged about my ride through the Pine Barrens with Jerry Dowgin and his vintage 305 Honda Scrambler a few years ago. The Journal article’s lead photo was of the Jersey Devil in front of Lucille’s (read on and you’ll see what I’m talking about), and that had my attention instantly. I had a great time with Jerry, and that ride and visit went on to become a featured article in Motorcycle Classics magazine.

Jerry went on to his reward a year or two after my visit, and I miss him. Read this blog, and if you can, the MC article. Jerry was a great guy and a good friend.

Rest in peace, Jerry.

I’d heard of the Pine Barrens when I was a youngster in New Jersey but I’d never been there, which was weird because the northern edge of the Pines starts only about 40 miles from where I grew up and geographically the Pine Barrens cover about a quarter of the state. New Jersey is the most densely populated state in the US, but you wouldn’t know it in the Pine Barrens. Pine trees and sand, lots of dirt roads, and not much else except ghost stories and New Jersey’s own mythological Jersey Devil (more on that in a bit). The region is mostly pine trees, but there are just enough other trees that our last-weekend-in-October ride caught the leaves’ autumn color change. That, the incredible weather, and saddle time on Jerry Dowgin’s vintage Honda Scrambler made it a perfect day.

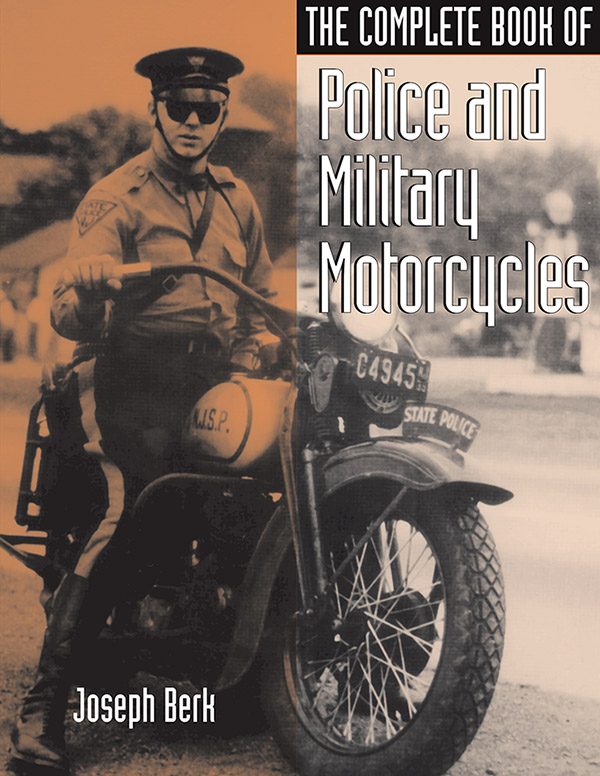

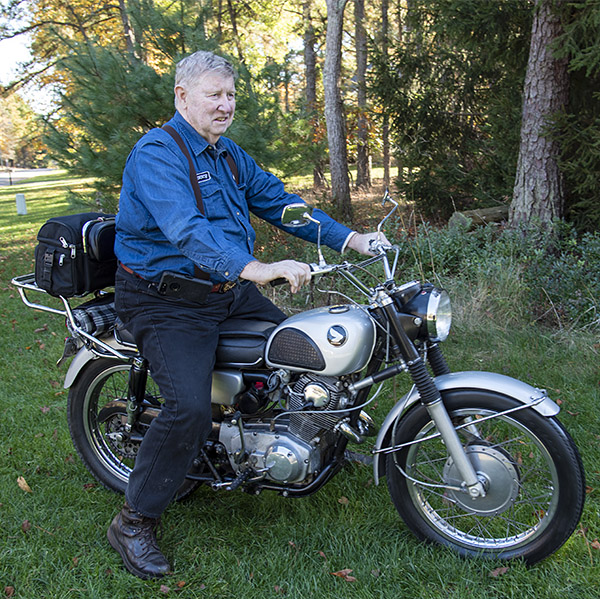

There were other things that made the day great. For starters, that has to include riding with Jerry Dowgin, former South Brunswick High School football hero, vintage motorcycle aficionado, and son of the late Captain Ralph Dowgin. SBHS is my alma mater (Go Vikings!), and the Dowgin name is legendary in New Jersey. I didn’t personally know Jerry when I was in high school (he was four years ahead of me), but I knew of his football exploits and I knew of his State Trooper Dad. Captain Dowgin commanded Troop D of the NJ State Police, and thanks to a photograph provided by lifelong good buddy Mike (another SBHS alum), Trooper Dowgin graces the cover of The Complete Book of Police and Military Motorcycles. Take a look at this photo of Jerry, and the Police Motors cover:

My ride for our glorious putt through the New Jersey Pine Barrens was Jerry’s 1966 CL77 Honda Scrambler. Jerry has owned the Scrambler for five decades. Jerry’s name for the Scrambler is Hot Silver, but I’m going to call it the Jersey Devil. The bike is not a piece of Concours driveway jewelry; like good buddy Gobi Gresh’s motorcycles, Jerry’s Jersey Devil is a vintage rider. And ride we did.

Honda offered three 305cc motorcycles in the mid-1960s: The Dream, the Super Hawk, and the Scrambler. All were 305cc, single overhead cam, air-cooled twins with four-speed transmissions. The CA77 Dream was a pressed steel, large fendered, single carb motorcycle with leading link front suspension. Like its sister Super Hawk, the Dream had kick and electric starting; the electric starter was unusual in those days. The Dream was marketed as a touring model, although touring was different then. Honda’s CB77 Super Hawk was a more sporting proposition, with lower bars, a tubular steel frame and telescopic forks, twin shoe drum brakes (exotic at the time), twin carbs, a tachometer, and rear shocks adjustable for preload. The engine was a stressed frame component and there was no frame downtube. Like the Dream, the Super Hawk had electric and kick starting. It’s been said that the Super Hawk could touch 100 mph, although I never saw that (my Dad owned a 1965 Honda Super Hawk I could sometimes ride in the fields behind our house).

The third model in Honda’s mid-‘60s strategic triad was the CL77 Scrambler, and in my opinion, it was the coolest of the three. It had Honda’s bulletproof 305cc engine with twin carbs, and unlike the Super Hawk engine, it was tuned for more torque. The Scrambler didn’t have electric starting like the other two Hondas (it was kick start only, a nod to the Scrambler’s offroad nature). The Scrambler had a downtube frame, no tach (but a large and accurate headlight-mounted speedo), a steering damper, and a fuel tank that looks like God intended fuel tanks to look (with a classic teardrop profile and no ugly flange running down the center). The bars were wide with a cross brace. With its kick start only engine, the magnificent exhaust headers, and Honda’s “we got it right” fuel tank, the Scrambler looked more like a Triumph desert sled than any other Honda. In my book, that made it far more desirable. I always wanted a Scrambler.

Jerry and I had great conversations on our ride through the Pine Barrens. We talked motorcycles, the times, the old times, folks we knew back in the day, and more. Other riders chatted us up. The Scrambler was a natural conversation starter. Every few minutes someone would approach and ask about Jerry’s Scrambler. Was it original? Was it for sale? What year was it? I had a little fun piping up before Jerry could answer, telling people it was mine and I’d let it go for $800 if they had the cash. I can still start rumors in New Jersey, you know.

The 305cc Honda twins of the mid-1960s were light years ahead of their British competitors and Harley-Davidson. British twin and Harley riders made snide comments about “Jap crap” back in the day (ignorance is bliss, and they were happy guys), but at least one Britbike kingpin knew the score and saw what was coming. Edward Turner, designer of the Triumph twin and head of Triumph Motorcycles, visited Honda in Japan and was shocked at how advanced Japanese engineering and manufacturing were compared to what passed for modern management in England. No one listened to Turner. The Honda 750 Four often gets credit for killing the British motorcycle industry, but the handwriting was already on the wall with the advent of bikes like Honda’s Dream, the Super Hawk, and the Scrambler. I believe we’re living through the same thing right now with motorcycles from China. Or maybe I just put that in to elicit a few more comments on this blog. You tell me.

I’m always curious about how others starting riding, so I asked Jerry if he inherited his interest in motorcycles from his motor officer Dad. The answer was a firm no. “Pop wasn’t interested in motorcycles; he saw too many young Troopers get killed on motorcycles when he was a State Trooper.” Jerry’s introduction into the two-wheel world was more happenstance than hereditary. He was working with his brother and his brother-in-law installing a heating system in a farmhouse when they encountered the Scrambler. Jerry bought his 1966 Scrambler in 1972 for the princely sum of $10. Yes, you read that right: $10. The Scrambler wasn’t running, but the deal he made with his brother was that Jerry would do the work if his brother would pay for the parts (and in 1972, the parts bill came to $125 from Cooper’s Cycle Ranch, one of the early and best known East Coast Honda and Triumph dealers). Getting the Scrambler sorted took some doing, as the engine was frozen, it needed a top end overhaul, it had compression issues, and getting the timing right was a challenge. But Jerry prevailed, and the bike has been a Pine Barrens staple for five decades now.

Jerry shared with me that he plans to leave his Honda Scrambler to his son and grandson. I think that’s a magnificent gesture.

Our ride in the Pine Barrens was most enjoyable. It’s amazing how little traffic there is in the Pines, an unusual situation for me. As a son of New Jersey, riding with no traffic in the nation’s most densely populated state was a new experience. But there’s a lot of land down there in the Pine Barrens (the area was a featured spot for dumping bodies on The Sopranos, and that probably wasn’t just a figment of some screenwriter’s imagination). Riding into the Pines (where we saw few other motorcycles and almost no cars), we made our first stop in Chatsworth. Chatsworth is an old Pine Barrens wide spot in the road with only a few buildings and a roadside eatery with no seating. You buy a soda and a dog (of either the hot or brat variety), find a seat on one of the roadside benches, and chat with other riders. It was different and much more fun than what I remembered New Jersey riding to be, but I had never ridden the Pines before. The locals told me it’s always been like this.

From Chatsworth, it was on to Lucille’s Country Diner, a popular Pine Barrens roadhouse more like a California motorcycle stop than a New Jersey diner. Lucille’s is known for its pies, and (trust me on this) they’re awesome. We parked under a carved, presumably life-sized Jersey Devil statue. I’d heard of the Jersey Devil when I was a kid (it’s a New Jersey thing; think of it as a cross between Bigfoot and Lucifer and you’ll understand). We didn’t see the Jersey Devil lurking out there in the pine trees on this ride, but who knows? Maybe he saw us. As a New Jersey native, I know this: Anything’s possible in the Garden State.

Never miss an ExNotes blog. Get a free subscription here:

Keep us afloat: Click on those popup ads!

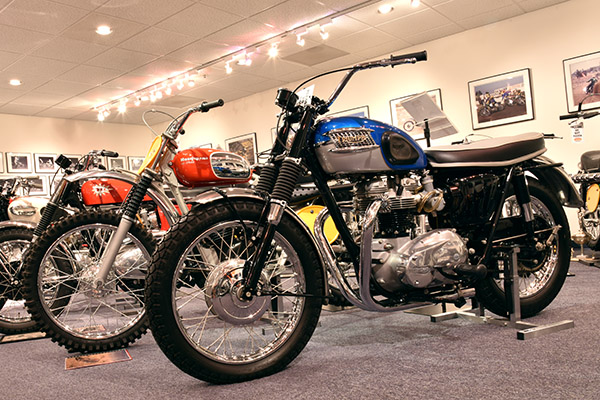

Mostly Bultacos and Maicos were racing in Haines City back then but one guy had an Ossa Pioneer with the lights removed. The rider was good. He would get crossed up over the jumps and finished in the top 5 against real race bikes. I loved how the rear fender blended into the bike. That fiberglass rear section had a small storage area inside. One of the bike magazines of the era tossed a loose spark plug in the storage and went scrambling. The plug beat a hole in the rear fender and they had the nerve to bitch about it. Hell, I knew at 10 that you have to wrap stuff in rags on a motorcycle.

Mostly Bultacos and Maicos were racing in Haines City back then but one guy had an Ossa Pioneer with the lights removed. The rider was good. He would get crossed up over the jumps and finished in the top 5 against real race bikes. I loved how the rear fender blended into the bike. That fiberglass rear section had a small storage area inside. One of the bike magazines of the era tossed a loose spark plug in the storage and went scrambling. The plug beat a hole in the rear fender and they had the nerve to bitch about it. Hell, I knew at 10 that you have to wrap stuff in rags on a motorcycle. It rains most everyday in Florida and it started pouring. The races kept going for a while but finally had to be called because it was a deluge. You could hardly see to walk. There was no cover so we huddled in the leeward side of the ticket stand out by the entrance. It rained harder, the wind was howling. Wearing only shorts and T-shirts we were getting colder and colder. My lips were turning blue, man.

It rains most everyday in Florida and it started pouring. The races kept going for a while but finally had to be called because it was a deluge. You could hardly see to walk. There was no cover so we huddled in the leeward side of the ticket stand out by the entrance. It rained harder, the wind was howling. Wearing only shorts and T-shirts we were getting colder and colder. My lips were turning blue, man.