Necessity is the mother of invention, or something like that. When I heard that IMR 4320 was discontinued (on top of the ammo and components shortage), I was not a happy camper. IMR 4320 was my go to powder for several cartridges, and now what I have left is all there is (and it’s almost gone). But it really doesn’t matter, because we can’t hardly find propellants of any flavor. That notwithstanding, I made the trek to my local components supplier a couple of weeks ago, and he had only three propellants left: IMR 4166, 8208, and BLC2. I’ve never used any of these, although I had heard of Ballsy 2. The 4166 seemed interesting…it matched my motorcycle jacket, but none of my reloading manuals had any data for it (it’s that new). I bought all three.

I went online and found data published by the manufacturer, so I worked with that for my 30 06. IMR 4166 is an extruded stick powder. It will flow through a dispenser, but the dispenser throw variability was about 0.2 grain, and that’s enough when loading for rifle accuracy that I’ll weigh every charge with my scale and trickle it in with my RCBS powder trickler.N Would 0.2 grains make an accuracy difference? I don’t know (and someday I’ll test to find out). I suspect not, but weighing every charge only takes a few seconds more, and it seems like the right thing to do.

On the IMR website, it said that Enduron IMR 4166 is one of a new class of propellant that offers four adventages:

Copper fouling reduction. These powders contain an additive that drastically reduces copper fouling in the gun barrel. Copper fouling should be minimal, allowing shooters to spend more time shooting and less time cleaning a rifle to retain accuracy. Hmm, that might be interesting. We’ll see how it does, I thought to myself as I read this.

Temperature change stability. The Enduron line is insensitive to temperature changes. Whether a rifle is sighted in during the heat of summer, hunted in a November snowstorm or hunting multiple locations with drastic temperature swings, point of impact with ammunition loaded with Enduron technology will be very consistent. In the old days, I might have dismissed this as a solution looking for a problem, but I’ve experienced what can happen in a temperature sensitive powder. I had a max load for my 7mm Weatherby that was fairly accurate that I took out to the range one day when it was 107 degreees. I fired one shot and had great difficulty getting the bolt open. It’s a real issue if you develop a load at one temperature and then shoot it at an elevated temperature. If IMR 4166 is free from that characteristic, that’s a good thing.

Optimal load density. Enduron powders provide optimal load density, assisting in maintaining low standard deviations in velocity and pressure, a key feature for top accuracy. Eh, we’ll see how it does on paper. I have some loads that are low density (i.e., they occupy well under 100% of the case volume) and they shoot superbly well. I’m interested in how the load groups. The target doesn’t give extra credit if an inaccurate load has a low standard deviation.

Environmentally friendly. Enduron technology is environmentally friendly, crafted using raw materials that are not harmful to the environment. Okay, Al Gore. Gotcha. Now go back to inventing the Internet.

My test bed for the new powder would be a Model 700 Euro in 30 06, a 27-year-old rifle I bought new about 10 years ago. I had just refinished it with TruOil and glass bedded the action (a story a future blog, to be sure), and I hung a cheapie straight 4X Bushnell scope just to get a feel for how everything might perform.

My load was to be a 180-grain Remington Core-Lokt jacketed soft point bullet and 47 grains of the IMR 4166, all lit off by a CCI 200 primer. If you’re interested, I was using Remington brass, too. The cartridges were not crimped.

Wow, those 180-grain bullets pack a punch. Recoil was fierce, and I probably felt it more because the Model 700 doesn’t have a recoil pad.

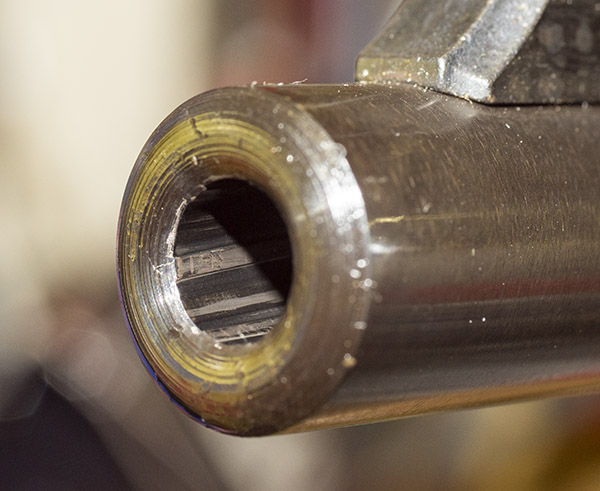

Okay, that’s enough about my heroics. Let’s take a quick look at how the propellant performed. With regard to the reduction in copper fouling claim, I’d have to say that’s an accurate claim. After 20 rounds (the very first through this rifle), I ran a single patch with Hoppes No. 9 though the bore, followed by a clean patch, just to remove the powder fouling. There was a very modest amount of copper fouling, way less than I would have seen with any other propellant. Ordinarily, at this point in the cleaning process (i.e., removing the soot) I would normally see a bright copper accent on top of each land. With 4166, there was only a minimal amount of copper present (as you can see below). After a second patch with Hoppes No. 9, the copper was gone. I guess this copper fouling eliminator business is the real deal.

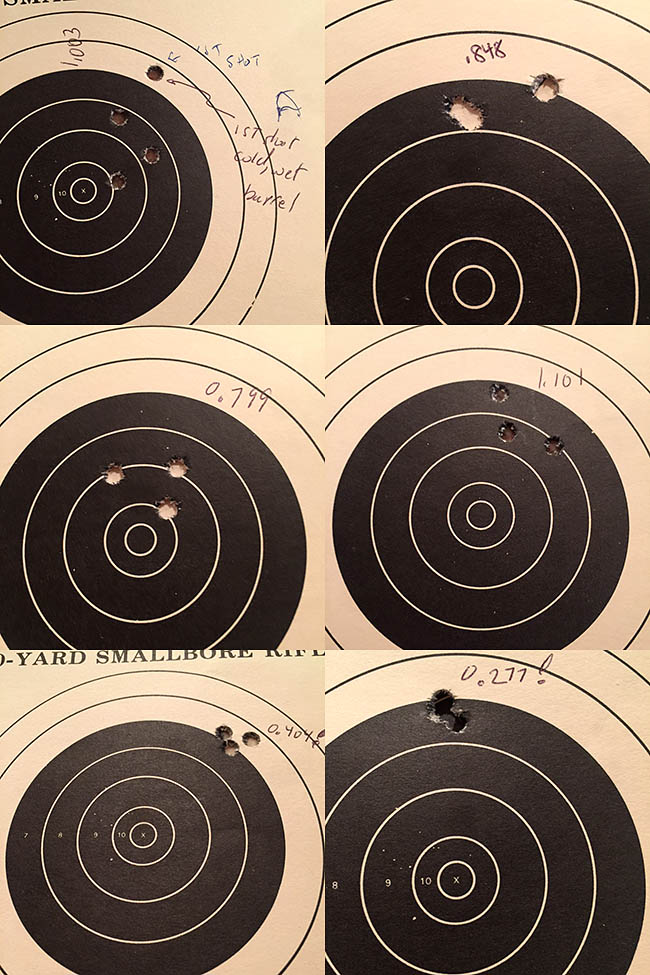

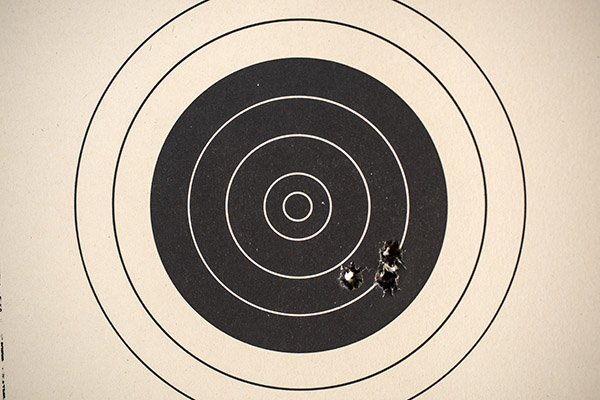

With regard to accuracy, 4166 has potential. I shot five targets that afternoon, and this was the best. It’s a 0.590-inch group at 100 yards, and that ain’t too shabby.

The bottom line for me is that IMR 4166 is a viable powder. Now, like everyone else, I need to find more. That’s going to be a challenge. But at least I know that my IMR 4320 has a decent replacement.