Folks my age love steam locomotives. I think it’s because they were still pulling trains and generating revenue when I was a kid. The Lionel thing probably figures into the equation, too. Most guys my age had a Lionel train set when they were boys. I did, and I loved it. Some guys are still into it, like good buddy Steve. Anyway, the point is when I’m traveling, I never miss an opportunity to visit a railroad museum.

A few months ago when we were back east, our travels allowed us to swing by Scranton, Pennsylvania, and visit the Steamtown National Historic Site. It’s part of the US National Park network, but if you don’t have the senior discount card, don’t worry about it. Admission is free.

The tour started with a movie, and it was great. It told a lot about the early days of railroad travel in America, and it had an interesting section on mail cars. I’ll get to that in a second.

After the movie, you follow the marked path and see several locomotives and a mail car. Some of those photos are coming up (I used my Nikon D810 and the 24-120 Nikon lens for all the photos you see here). After that, the path takes you outside again to see the roundtable. That’s what locomotive repair facilities used to rotate locomotives and put them on the right tracks. Here’s a photo of the roundtable.

It might seem mundane, but the movie told an interesting story about this aspect of railroad history and seeing an actual mail car immediately after was a nice touch.

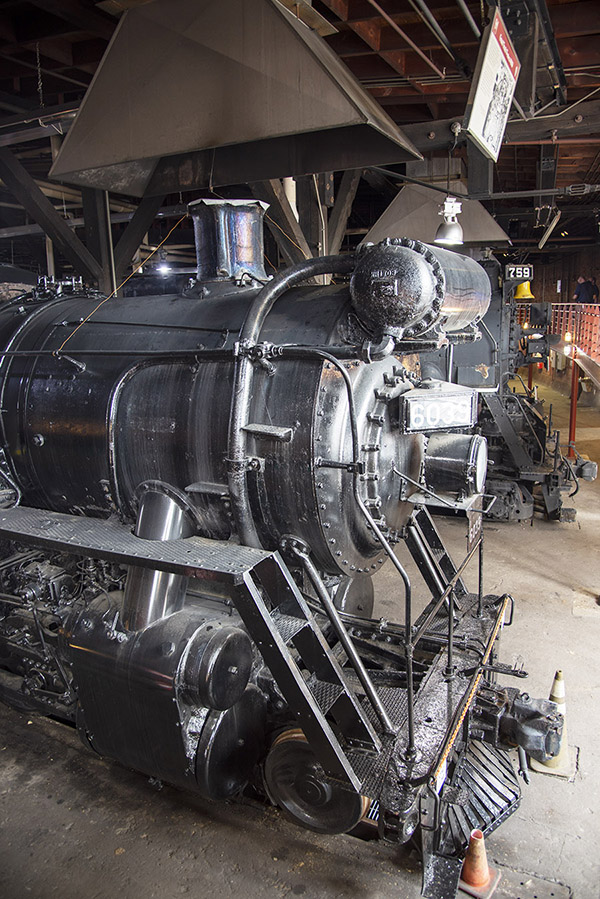

The locomotives in the maintenance shop were interesting. Photographing these would ordinarily be a challenge because of the dimly-lit buildings and the black locomotives, but the Nikon 810 and the 24-120 lens vibration reduction technology handled it well. That combo has superior low-light capabilities. All of these photos are hand-held shots with no flash.

The displays included a cutaway locomotive that showed a steam locomotive’s innards. I had studied steam generation as an undergraduate engineering student and like I said, I was a Lionel guy when I was a kid, but I had no idea. This stuff is fascinating.

We walked around outside and I grabbed photos of some of the locomotives in the yard. This one was obviously unrestored. It was pretty cool.

The rail yard had a Reading Lines diesel electric locomotive on display, too. Most folks just call these diesels, but propulsion was actually via electric motors in the trucks (a truck is the subchassis that carries the wheels, the axles, and the electric motors). The diesel engine is used to turn a generator that provides electricity to the motors. If this sounds suspiciously like a modern hybrid automobile, it’s because it is.

As we left, it was just starting to rain. It was overcast the entire time we visited Steamtown National Historic Site. I was okay with that, because overcast days are best for good photography. I stopped to grab a few photos of the Big Boy parked at the entrance to the site.

These Big Boy locomotives are a story all by themselves. They were the largest steam locomotives ever built, designed specifically for the the Union Pacific Railroad by the American Locomotive Works. They are articulated, which means their 4-8-8-4 wheel set (4 little wheels, 8 big drive wheels, 8 more big drive wheels, and then 4 more little wheels) are hinged underneath the locomotive so the thing can negotiate curves. The Big Boys were created for the specific purpose of pulling long trains up and over the Rocky Mountains. They only made 25 of them. We had one here in my neighborhood a few years ago and we wrote about it on the blog.

Which brings me to my next point. I started this blog by saying that folks my age love steam locomotives. I guess that pertains to Gresh and me, as it seems we’ve done a number of ExNotes blogs that include railroad stuff. Here you go, boys and girls.

The California State Railroad Museum

Big Boy!

The Nevada Northern

Golden Spike National Historic Park

Going Nowhere, Slowly

Santa Rosalia’s Hotel Frances

A TT250 Ride

Pennsylvania is a beautiful state. I grew up one state over (in New Jersey), and a lot of the folks I knew in New Jersey relocated to Pennsylvania because of the more rational tax structure. There are beautiful motorcycle roads in Pennsylvania, too, once you get off the freeways and start exploring. If you make it to Scranton, the place has great restaurants, and like most east coast locales, the Italian food is the best in the world (even better than Italy, in my opinion). Try Vincenzo’s for pizza. It was awesome.

Never miss an ExNotes blog!