By Joe Gresh

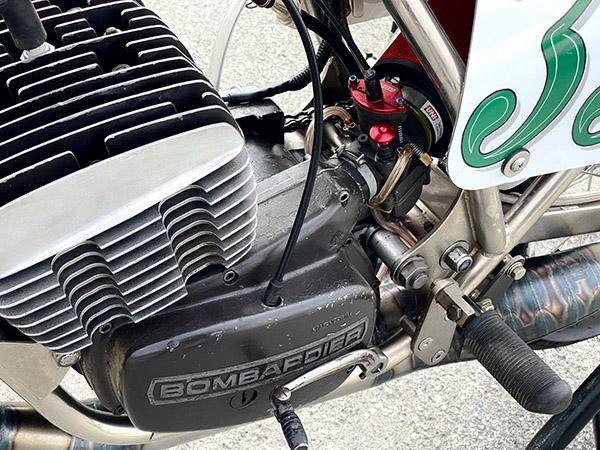

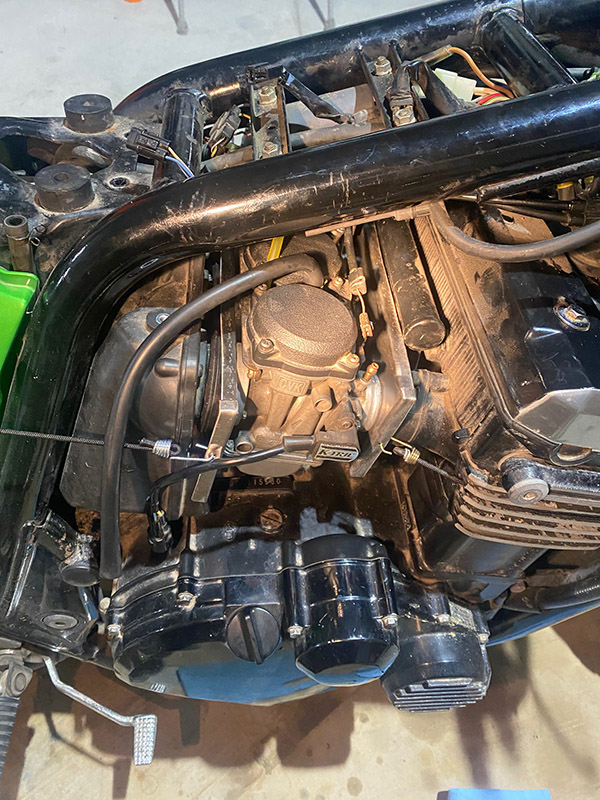

The first time I cleaned the carburetors on the Kawasaki ZRX1100 everything went well except for the part about removing and installing the carbs back on the engine. The ZRX had sat for 9 years and it wasn’t running all that well when I parked it. The first carb cleaning saw new float needles installed and a general poking and cleaning of all jets and orifices.

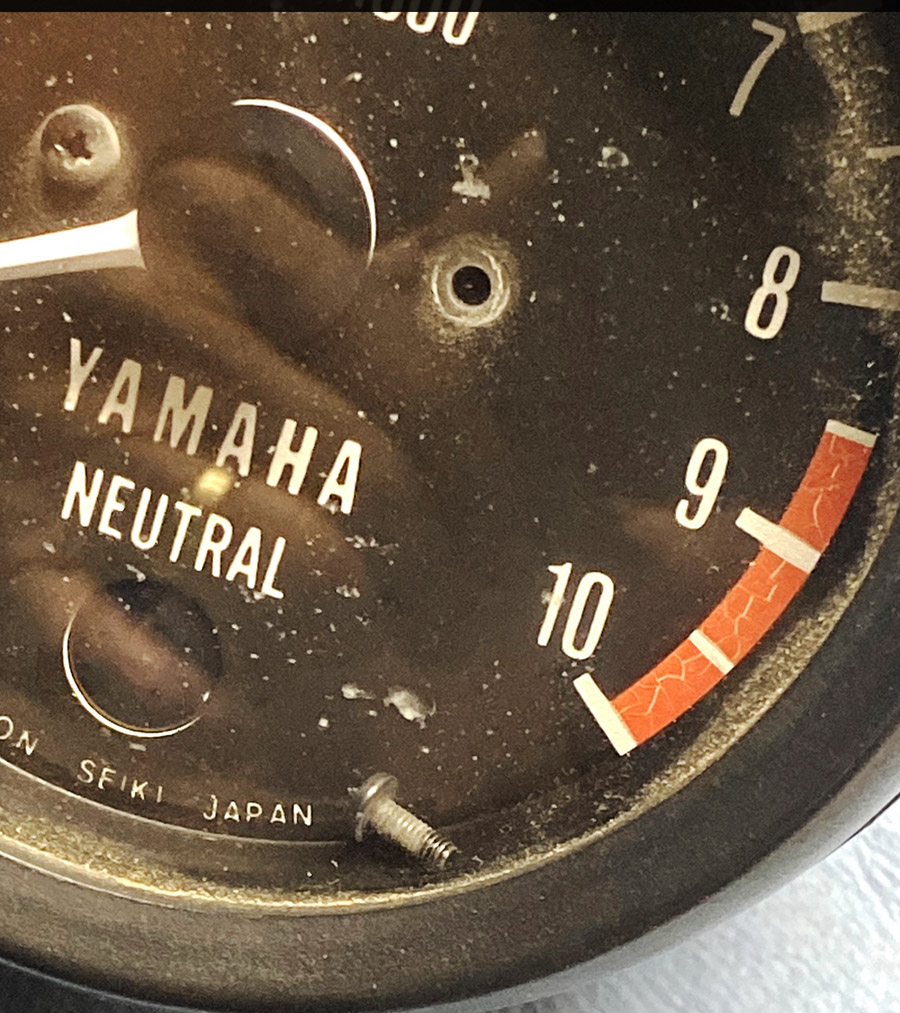

The bike started up okay and ran fairly well, if a bit ragged at low RPM. This I chalked up to the four carbs needing synchronization. I didn’t have a carb sync tool so I just ran it like it was. It ran pretty good for 7000-8000 miles but became harder to start and really rough at any RPM below 2500. I put up with it because I dreaded removing the carbs again.

The old, original fuel hose started leaking where I had installed an inline fuel filter. No matter what clamp I used it leaked. Giving it a through examination I discovered the hose itself was rotten and the inner liner split. I pulled the hose off and sealed my fate. It was impossible to reach the hose connection buried between the carbs to install a new hose. Things had finally gotten so bad I had to fix the situation.

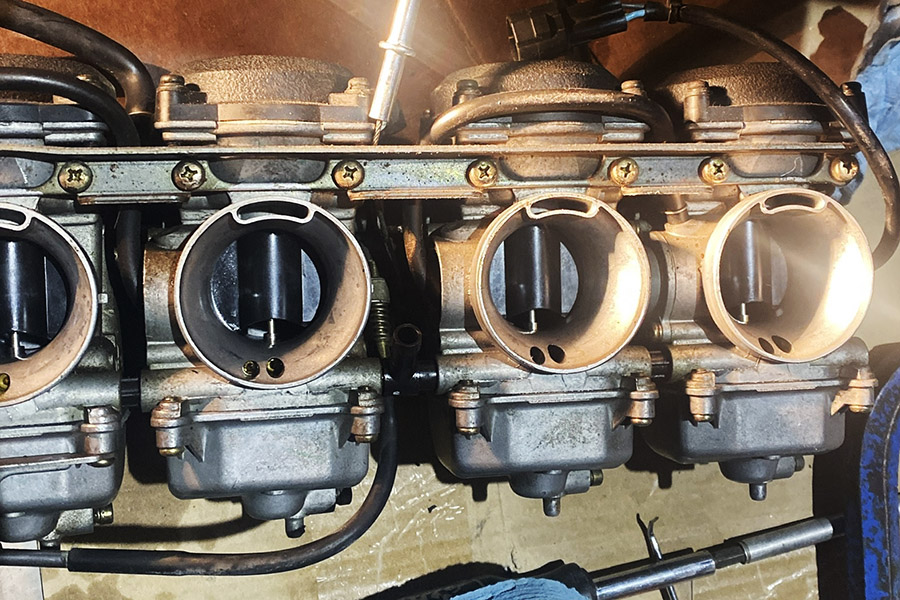

Removing the carbs was as dreadful as I remembered it to be. There’s not a lot of room between the air box and the intake rubbers so it was a bear (like an Ossa!) to remove the bank of four constant velocities.

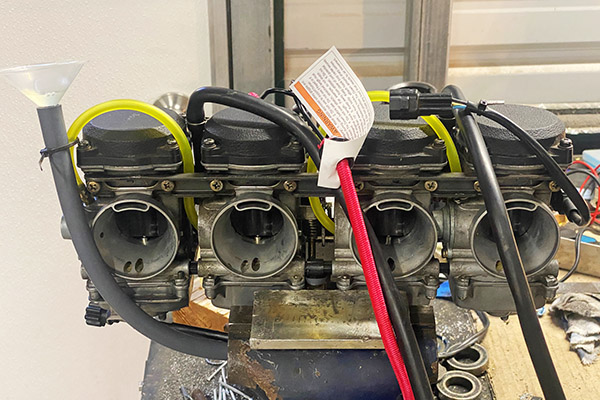

Once on the bench the Kawasaki ZRX1100 carbs are pretty easy to work on. I ordered new carb kits and new fuel pipes that go between the carbs to supply fuel. The old pipes weren’t leaking but I didn’t want to go through this ordeal only to have them start leaking.

To install the new fuel pipes you have to un-rack the carbs and split them into individual units. The old pipes looked pretty crusty and I can see them puking fuel because I disturbed them once too often. I also wanted fresh plastic to replace the 24-year-old pipes. While I was at it I bought factory coolant hoses to replace the silicone ones that leaked when it was cold. The new hoses fit much better and should last the rest of my life. All in, I spent three hundred bucks with Dave at Southwest Suzuki/Kawasaki out on Highway 70.

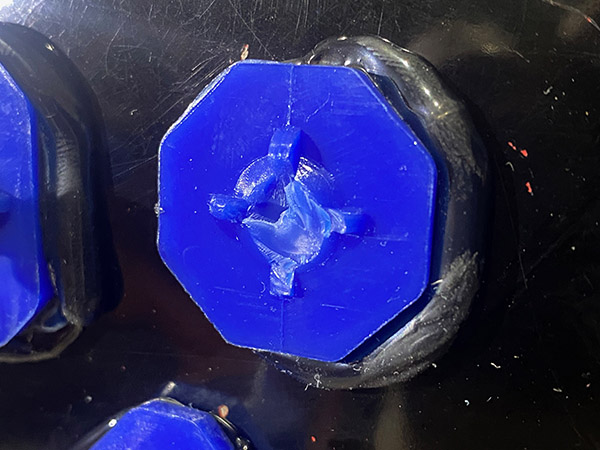

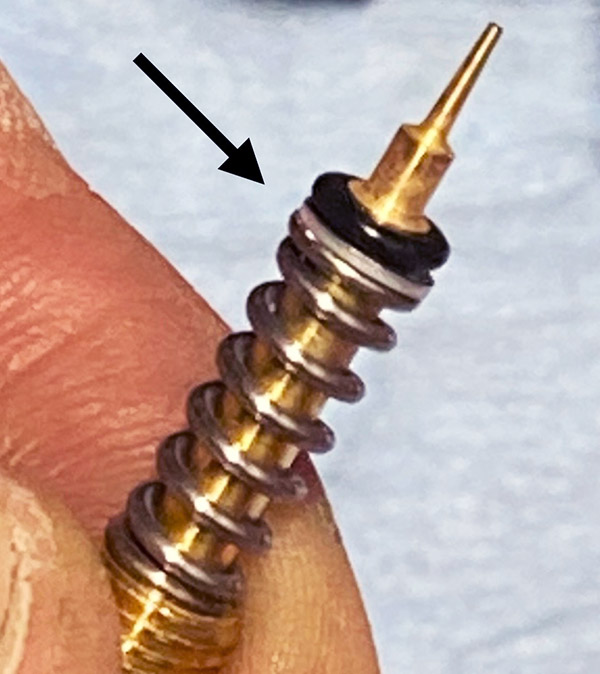

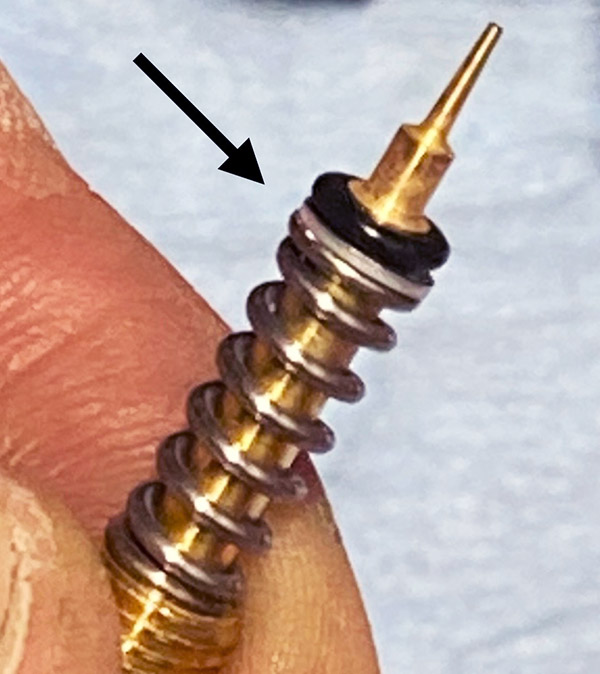

Two of the pilot jets were clogged solid. I had just cleaned them a few months or 8000 miles ago. Possibly the rotten fuel line sent debris down stream and clogged the jets. In addition there are supposed to be tiny washers between the o-ring and the tension spring on the pilot jet adjusting screws. Three were missing and I must have lost them the last time I took the carbs apart. Without the little washers the tension spring digs into the o-ring shredding the thing. Any pieces of o-ring go right into the tiny idle transition holes on the floor of the venturi. So that’s on me. I swear, I never saw the things.

When I say the pilot jets were clogged I mean clogged. I soaked the pilot jets in Evaporust and tossed them into the ultrasonic cleaner: No joy. I had to use a single strand of copper from a fine strand electrical wire and work it for 20 minutes to get the things cleared.

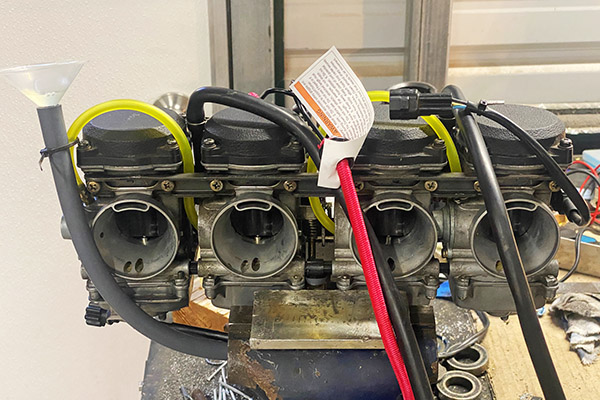

The new Parts Unlimited carb kits came with all the stuff I needed, even those tiny idle mixture screw washers. I usually don’t use the jets out of kits because the quality is so suspect. In this case I decided to use them to be sure the pilots were clear enough. Besides, it couldn’t run any worse. I rechecked the float levels, one was a millimeter off, and assembled the entire mess.

The next day it occurred to me that I had installed the new jets without making sure they were actually drilled all the way through or that a bit of machining swarf hadn’t been left inside. So I took the float bowls off and ran copper wire through all four pilot jets and the main jets. It was good for my peace of mind. I also sprung for an OEM Kawasaki fuel line at a reasonable $12.

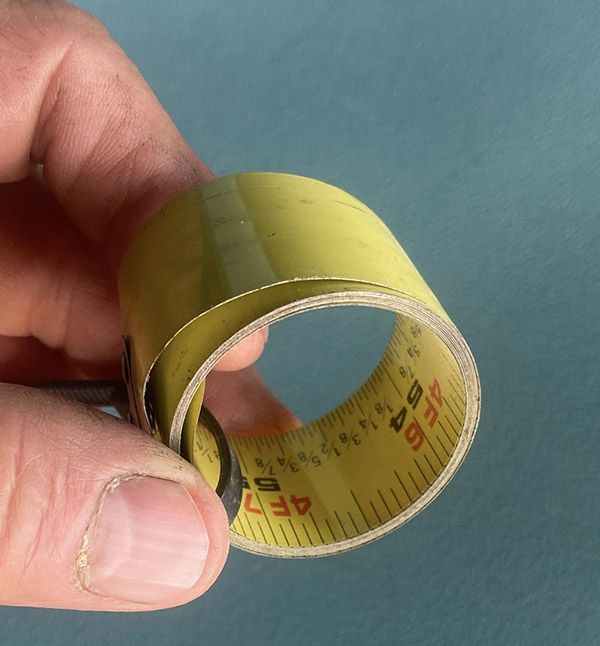

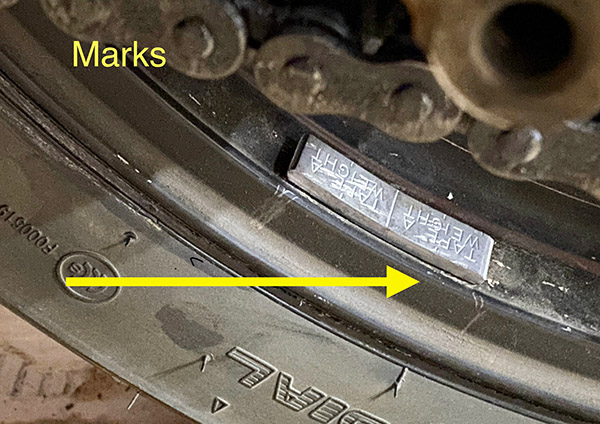

Because they are so hard to remove I try to be sure the carbs are not leaking by bench testing the floats and needles. This will save you a lot of work in the event something isn’t right. There’s nothing more depressing that fighting the carbs back into place only to have the things leak when you turn the petcock to On.

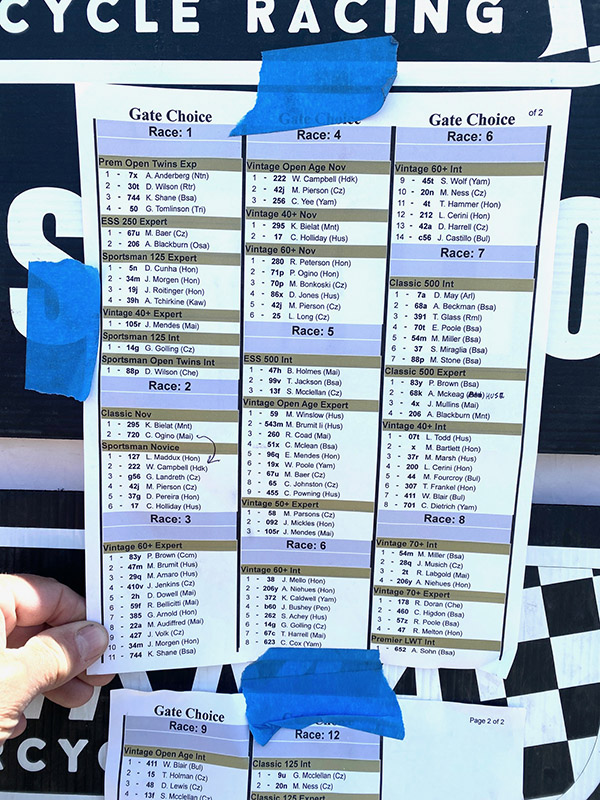

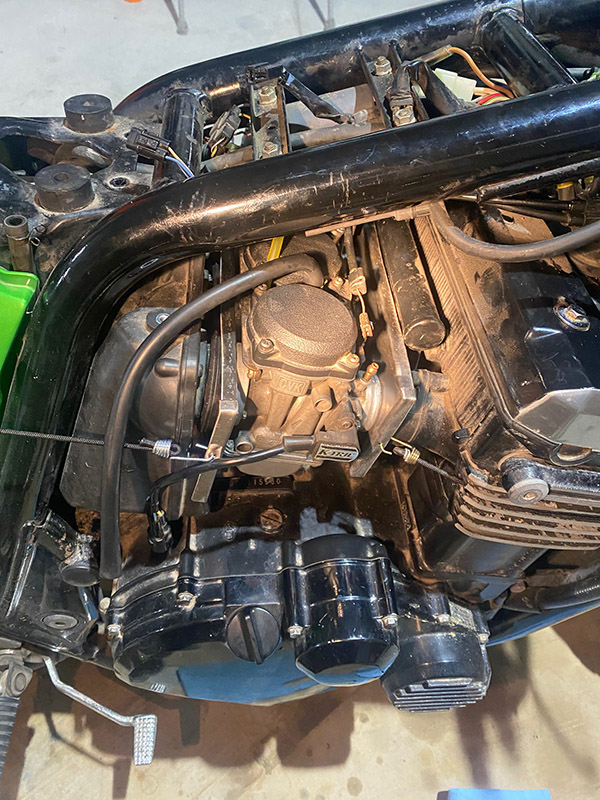

As you may have heard I was banned from the ZRX owner’s forum because I posted an ExhaustNotes light bulb review. It didn’t sit well with the members that were selling light bulbs. My new ZRX hangout is on Facebook called Banned ZRX members, or something like that. A lot of the same guys who were on the other site ended up there due to disagreements with the admin. Anyway, these ZRX guys suggested a thin piece of material between the air box and the rubber intakes to make replacing the carbs easier.

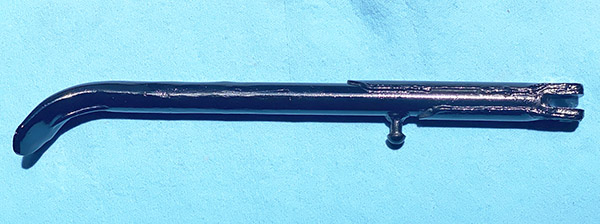

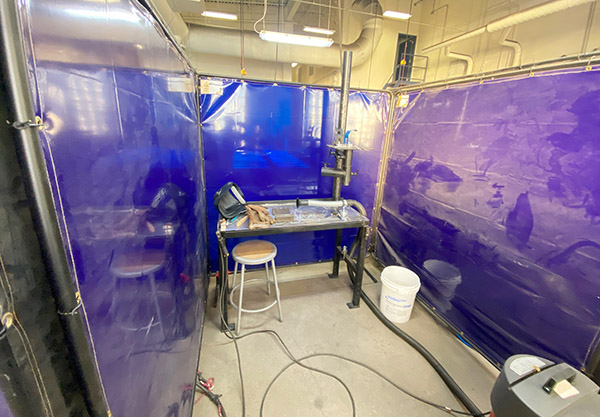

I had some thin sheet metal from a filing cabinet and used it to make two carb slider thingies. The sliders are held onto the engine by small bungee cords. I put a 90-degree bend in the sliders so they wouldn’t slip down in use. Those ZRX guys know their stuff, as it was a breeze to slide the carbs into position then remove the sheet metal. That’s half of a hard job made easy.

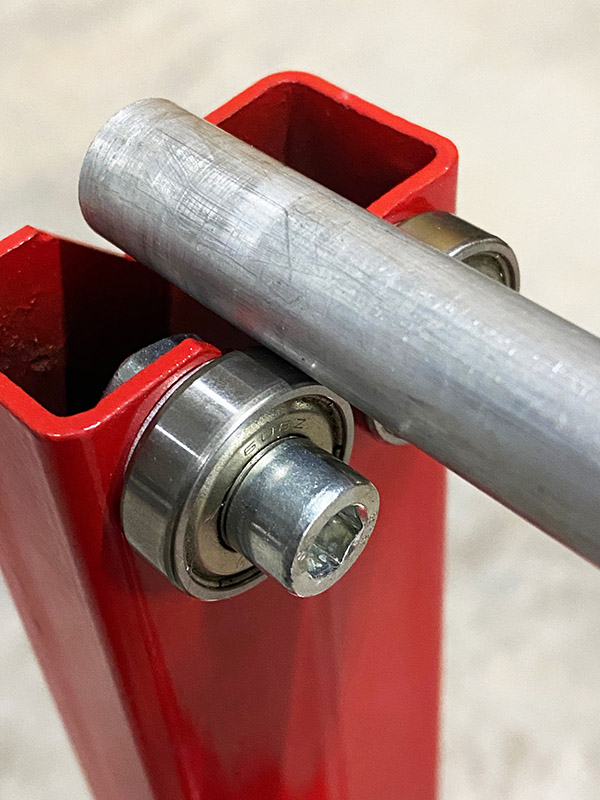

The Kawasaki ZRX1100 has a lot going for it in the maintenance department. The valves are easy to set clearances. The carbs use three simple, spring-loaded adjustment screws for synchronization, and there are no lock nuts to cause changes when tightened. The procedure is simplicity: You adjust the left set of two outside carbs, then adjust the right set of outside carbs, then adjust both sets of carbs to each other using a middle adjusting screw. It actually takes longer to write the carb sync procedure than to do it.

With all four idle circuits functioning correctly the ZRX starts up first push of the button. The bike pulls smoothly from idle all the way to redline. Having the carbs synced makes for a smooth transition coming off a stop and I don’t think the bike has ever run as good as it does now. I’ll be heading to Utah in June for the Rat Fink convention. It will be a lot more fun with the bike running like Kawasaki intended.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

Don’t forget: Visit our advertisers!