Good buddy Peter asked me to post a map of our recent Royal Enfield adventure ride to see the whales in Baja. That was a great suggestion, and it also provides an opportunity to suggest a great 7-day itinerary to see the whales in Baja. This was a relaxed ride of approximately 200 miles per day, and a full day off the bikes in Guerrero Negro on the day we saw the whales. One thing I want to mention up front: If you’re taking a motor vehicle into Mexico, you must insure the vehicle with a Mexican insurance policy. We insure with BajaBound, and that’s who we always recommend.

Day 1: The Los Angeles Basin to Tecate (170 miles)

The 170-mile distance I reference here is taking the 15 or the 5 south from the Los Angeles area. When you get down to the San Diego area, just find California 94 off the freeway, stay on it for about 25 miles heading east, and make a right on 188 for the 2-mile hop to Tecate.

You can make Tecate in about three hours if there’s no traffic. It’s an easy run and it gives you time to process into Mexico by picking up a visitor’s card, you can change U.S. currency into pesos, and you have time to explore Tecate a bit. An alternative route is to head south by riding over Mt. San Jacinto into Idyllwild and then take country roads through California down to Tecate, but you’ll need a full day if you do this and you would get into Tecate much later.

My advice for a Tecate hotel is either the El Dorado or the Hacienda (you get to either by running straight into Tecate and turning right on Boulevard Benito Juarez. If you are with your significant other, you might consider the Amores Restaurante for dinner (it’s world class fine dining and it is superb). If you want something simpler, go for Tacos Dumas, a short walk from the Hacienda Hotel. There’s also a great Chinese restaurant across the street from the Hacienda (there are a lot of great Chinese restaurants in Mexico).

Day 2: Tecate to San Quintin (180 miles)

Day 2 starts with breakfast at 8:00 a.m. at the Malinalli Sabores Autóctonos restaurant. It’s in the same building as the Hacienda Hotel, and as explained to us by Jonathan (the head chef at the Amores restaurant) it’s the best breakfast in Tecate. I think it’s the best breakfast anywhere, and with their exotic buffet featuring different Mexican regional cuisines, it will start your day right.

After breakfast, head east on Boulevard Benito Juarez, turn right when you see the sign for the wine country, and stay on that road (it becomes Mexico Highway 3) to Ensenada. It’s Mexico’s Ruta del Vino, and the scenery and the vineyards are grand.

After 70 miles of glorious wine country, you’ll hit Mexico Highway 1 just north of Ensenada. Turn left, hug the Pacific, and skirt through Ensenada (one of Baja’s larger cities). After Ensenada, you’ll pass through several small towns and then the road becomes the Antiqua Ruta del Vino, or Baja’s old wine country. The scenery is impressive. Stay on that road; you’ll pass through many small agricultural towns as you continue south through Baja. San Quintin is the destination on this second day of our Baja journey. There are lots of hotel options in San Quintin; my favorite is the Old Mill Hotel. Watch for the Old Mill Hotel sign, and make a right when you see it to reach San Quintin Bay and the hotel 4 miles to the west. Staying here is a tradition for Baja travelers.

There are two great restaurants on either side of the Old Mill, and the Old Mill now has its own restaurant, the Eucalipto. Good buddy Javier is the owner and head chef, and the cuisine is fabulous. You’ll get a free beer when you check into the hotel. Ask for a Modelo Negra; it’s superb.

Day 3: San Quintin to Guerrero Negro (264 miles)

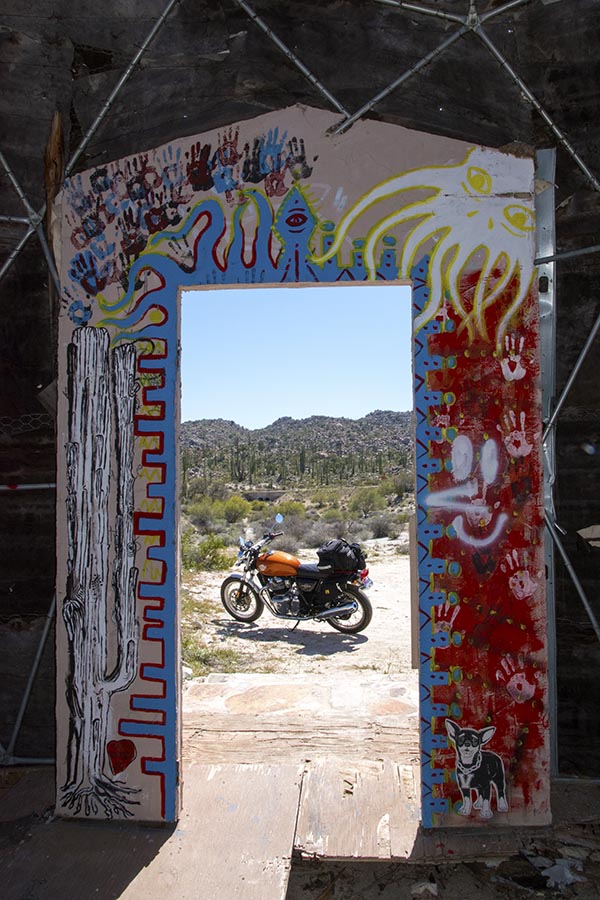

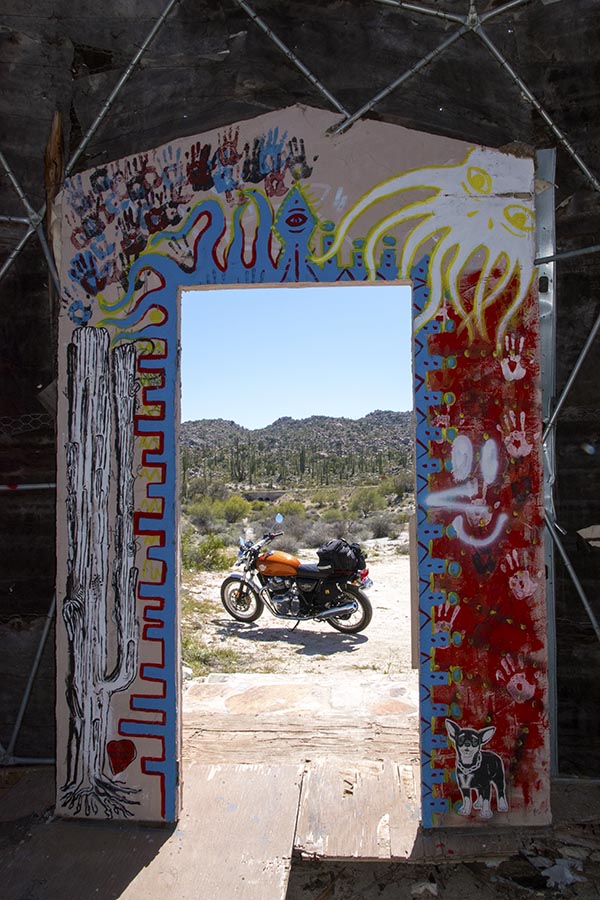

This is the long stretch, and it starts with a run south from San Quintin through Los Pinos, and then roughly 20 miles along a roller coaster road skirting the Pacific. Then it’s a climb into the hills, a Mexican military checkpoint, and you’ll arrive in El Rosario. Top off at the Pemex in El Rosario, and if you’re hungry, you might have a late breakfast or an early lunch at Mama Espinoza’s (try the chicken burritos; they’re awesome). After that the Transpeninsular Highway climbs into the Valle de los Cirios and the desolation that is Baja. You’ll see several varieties of plant life that grow in Baja and no place else on Earth (including the Dr.-Suess-like cirio and the mighty Cardon cactus).

It gets even better when you enter the Catavina boulder fields. The area around Catavina is a magnificent region with stunning scenes. There’s a hotel on the right side of the road that seems to change ownership every time I’m down that way. The food is good (but a little on the pricey side); the trick is to get there before any tour buses arrive. A new Los Pinos 7-11 type store recently opened across the street from the hotel and it looks like they’re putting gas pumps in, which is a good thing. For now, though, if you’re on a bike we advise filling up from the guys selling gasolina out of cans. It’s 110 miles to the next gas station, and most bikes don’t hold enough fuel to make the entire 231-mile run from the Pemex in El Rosario all the way to Guerrero Negro.

After the Catavina boulder fields, it’s a run through Baja’s Pacific coastal plains to Parallelo 28, the border between Baja and Baja Sur (the two states comprising the Baja peninsula). There’s an immigration checkpoint there where you might have to produce your visitor’s form, but usually the Mexican immigration folks just wave you through. Make a right turn off the Transpeninsular Highway, and head on in to Guerrero Negro.

There are plenty of hotels in Guerrero Negro. I’ve stayed at the Hotel San Ignacio (no restaurant), Malarrimo’s (one of the best restaurants in Guerrero Negro), the Hotel Don Gus (they have a good restaurant), and the Hotel Los Corrales. They’re all good. The real attraction here, though, is whale watching, and that’s the topic for Day 4 of our 7-day Baja adventure.

Day 4: Whale Watching in Guerrero Negro (0 miles).

Day 4 is a day off the bikes and a day devoted to whale watching. I always have breakfast at Malarimmo’s when I’m in Guerrero Negro. For whale watching, we’ve used Malarimmo’s and Laguna Baja’s tour service; both are great. They have morning and afternoon tours. Folks ask if the whale watching is better in the morning or the afternoon. I’ve found both are awesome (and both are just under $50 per person). The whale watching tours are only available January through March because that’s when the California gray whale herd is in Scammon’s Lagoon. You’ll be out on the boat for roughly three hours, so you’ll want to use the bathroom before you go. You can expect a genuine life-altering experience when you visit with the whales. You might think I’m exaggerating, but I am not. Bring a camera. No one will believe what you tell them about this experience unless you have pictures.

After seeing the whales, look for a fish taco van parked on northern side of the road. That’s my good buddy Tony’s Tacos El Muelle truck. Tony makes the best fish tacos on the planet. Yeah, I know, that’s another strong statement, but I know what I’m talking about here.

For dinner in Guerrero Negro, there are lots of options. The Hotel Don Gus has a great restaurant, Malarimmo’s is great, and we most recently tried the San Remedio (off the main drag on a dirt road in Guerrero Negro) and it, too, was awesome.

Day 5: Guerrero Negro to San Quintin (264 miles)

You might wonder: Are there other ways to head back north in addition to the way we came down? The short answer is yes, but the roads are sketchy and I’ve seldom felt a need to take a different route. My advice is to just go back the way you came down, and stop and smell the roses along the way. There’s plenty to see. Take photos of the things you missed. Enjoy the ride.

On the return leg of this adventure, you can stay at the Old Mill Hotel again. Yeah, it’s my favorite. There are other hotels in the San Quintin area, including the much larger and more modern Misione Santa Ines (which also has a great restaurant). There’s also Jardin’s, which Baja John told us about but I haven’t visited yet. One of these days I’m going to spend two or three days in and around San Quintin. It’s a cool area.

The Old Mill’s Eucalipto isn’t open every morning for breakfast, but that’s okay because there are lots of good places to eat once you get back on the Transpeninsular Highway heading north. If you want to pick one of the great breakfast spots, just look for any restaurante with a whole bunch of cars parked in front (the locals know what they are doing). If you’ve never had chilequiles, give this Mexican breakfast specialty a try.

Day 6: San Quintin to Tecate (180 miles)

This is the same ride we took on the way south, and my guidance is the same: Stop, smell the poppies, and grab a few photos along the way. If you can hold out for a great lunch, I have two suggestions. One is the Los Veleros in Ensenada, which is in the Hotel Coronado building as you ride along the coast. The other is Naranjo’s along the Ruta del Vino (Highway 3) back into Tecate.

I always like to stop at the L.A. Cetto vineyard on the way home (rather than on the first part of the ride). I’ll pick up one bottle of wine (and for me, that’s either a Malbec or a Cabernet). I’d like to be able to take more home, but it’s tough to do that on a motorcycle, and you’re only allowed to bring one bottle back into the United States. Rules is rules, you know.

If you had dinner at Tecate’s Amores on the way down, you might want to try a street taco restaurante on this, your second night in Tecate. We like Tacos Dumas, just up the street from the Hacienda Hotel. It’s awesome.

Day 7: The Ride Home (168 miles)

This is an easy run, and for me, it starts with a breakfast at Malinalli Sabores Autóctonos in Tecate (yeah, I love that place). After that, it’s a quick stop at the Mexican immigration office to return your tourist visa (don’t skip this step; you need to check out of Mexico and simply crossing back into the US won’t do that). If you’re in a car, you’ve got to get into the long line waiting to get back across the US border. If you’re on a bike, go a block or two east of the street you took into Mexico, turn left, and look for the US border crossing. There’s a break in the K-barriers guiding the automobile line, and you can go right to the head of the line. I’ve never had a problem doing this, even though it feels like I’m doing something wrong.

And folks, there you have it: Seven glorious days of the best riding on the planet. I’m ready to go again.

If you’d like to read the rest of our recent Royal Enfield Baja adventure ride posts, here are the links…

BajaBound on Royal Enfield

18 Again

The Bullet Hits Home

We’re Off

We’re Off 2

Snapshot

Tecate

San Quintin

Royal Enfield 650cc Twin: First Real Ride

The Plucky Bullet

Guerrero Negro

Ballenos

Whales

The Bullet in Baja

A Funny Thing

No One Goes Hungry

Day 7 and a Wake Up

The Bullet

The Bullet: Take 2

The Interceptor

One more thing…if you like what you see here, don’t forget to sign up for our blog update email notifications! We’re having our next drawing for one of our moto adventure books in just a few days, and getting on the email list gets you in the running!

Everything Joe Berk has written about the Bullet’s shaky performance on our Baja tour is true, but like our President’s spokeswoman has said, there are alternative facts in addition to real facts.

Everything Joe Berk has written about the Bullet’s shaky performance on our Baja tour is true, but like our President’s spokeswoman has said, there are alternative facts in addition to real facts.