It’s time to get out and do stuff. Yeah, this CV19 thing is a disaster, but it looks like what the wizards recommended is starting to produce results, and that gave me an excuse to get to the range again. Not that anyone ever needed an excuse to get to the range, but I felt like it was time, and that beautiful Henry Single Shot I’ve been writing about (but had not yet fired) was calling my name.

I had my Nikon with me, too, so I was finally able to get some good D810 photos of this beauty from Henry’s Rice Lake, Wisconsin manufacturing operation.

I wanted a couple of photos showing the entire rifle, and then I wanted to get a couple more showing the highly-figured walnut stock. The folks at Henry sure did a great job.

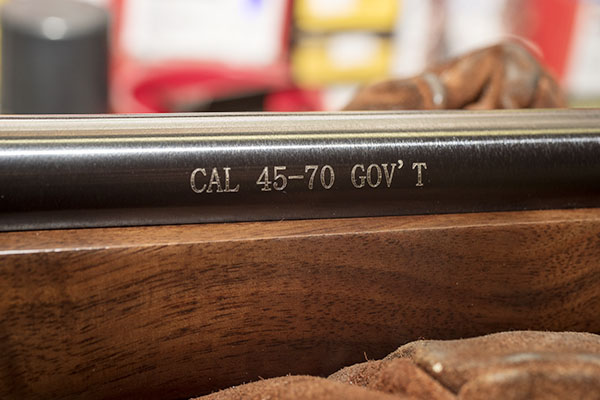

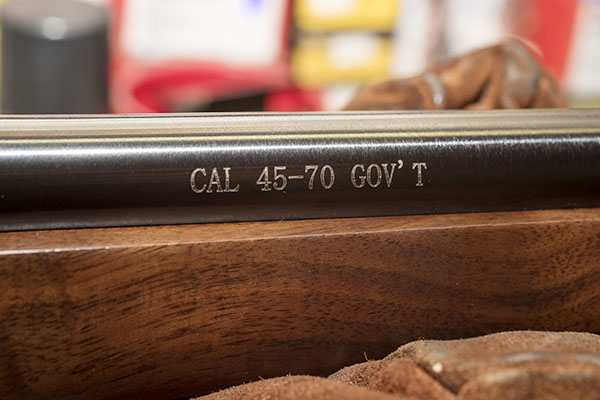

The .45 70 cartridge is a big one, and I’ve written about it in earlier blogs. There’s a list of links to our earlier blogs on the Henry single shot at the end of today’s post, along with a few other cool links. Take a stroll through them to get a feel for how I came to acquire this magnificent rifle (after you’re read this blog and shared it on all your social media platforms, of course).

It was fun shooting the Henry, both literally (more on that in a second), and figuratively (with the Nikon). The brass receiver on these guns photographs well, I think.

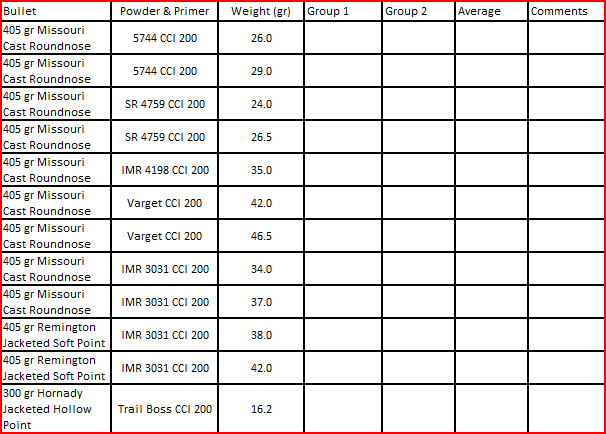

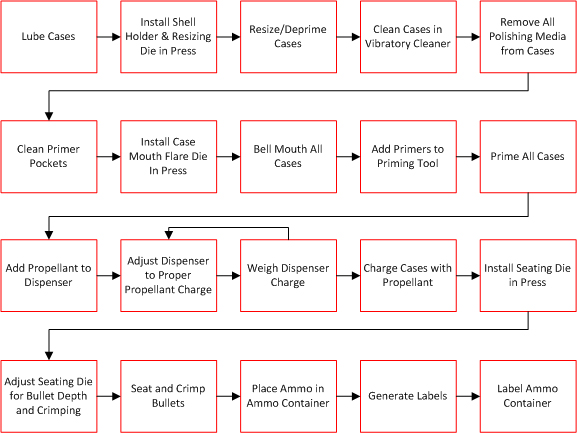

On to the good stuff, and that’s an answer to the most basic question for any firearm: How does it shoot? In a word or two, superbly well. I had a big plan to test all kinds of different loads, but I don’t want to bore you with the details of what didn’t work well and get right to what did.

First, a word on my marksmanship. It had been about 9 weeks since I’d been to the range, and the ability required to shoot a rifle well is not something you just pull out of drawer and pick up where you left off. Nope, rifle marksmanship is an art, and I needed to put a few rounds downrange before the Henry started performing. Well, actually, that’s not quite accurate: I had to send a few rounds downrange before I started performing. There’s a skill set involved in shooting a rifle well. You can read our treatise on rifle marksmanship later (I’ll include a link for that at the end of this article, too).

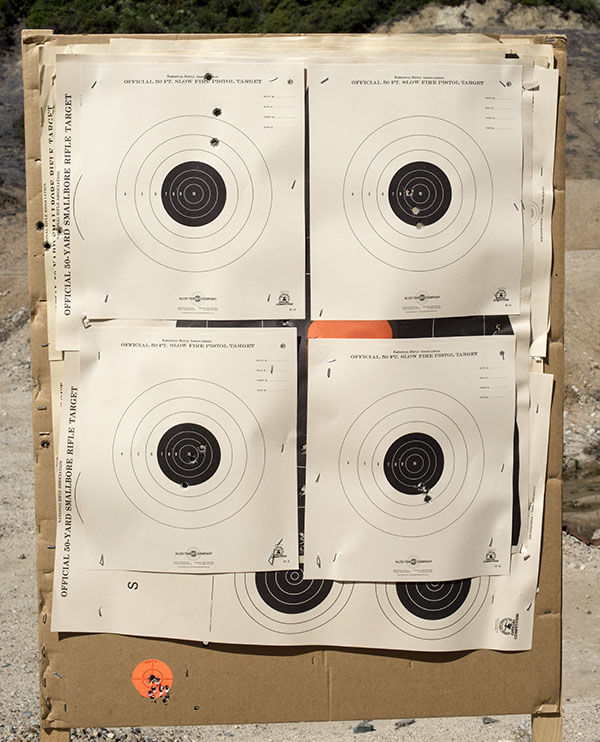

I started with four targets this morning at 50 yards and the results were not what I wanted, but I knew it was me and not the rifle. So I put another four targets out, and I started to settle down. It was a beautiful morning out at the West End Gun Club. Bright skies, mild temperatures, no wind, and I had the range to myself. It wasn’t too long before I was in the groove. The first target (the top left) was a bit shaky (good enough for deer or hog, and especially good enough for buffalo), but not what I knew I should be able to do with this rifle. The second target (top right) was a lot better, as I was kind of figuring out how to get the right sight picture. Shooting with iron sights is much more challenging than simply laying a scope’s crosshairs on the bullseye. Iron sights demand skill and practice. With 9 weeks away from the firing line, I was coming up short on both, but I was getting my groove back. I could feel it. The third target (bottom left) was another good deal, and then the fourth target sealed the deal. That one was a 0.740-inch group, with all the holes touching. With open sights on a lightweight .45 70 at 50 yards, I’ll take three-quarter-inch groups all day long.

Here’s another photo of my last target of the day, showing that beautiful 0.740-inch group. Bring on the buffalo. I’m ready. So is my Henry.

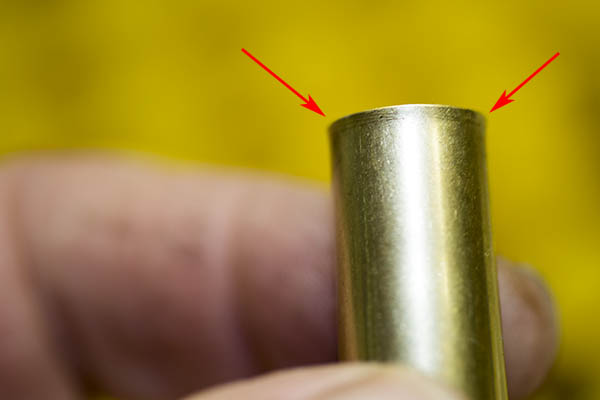

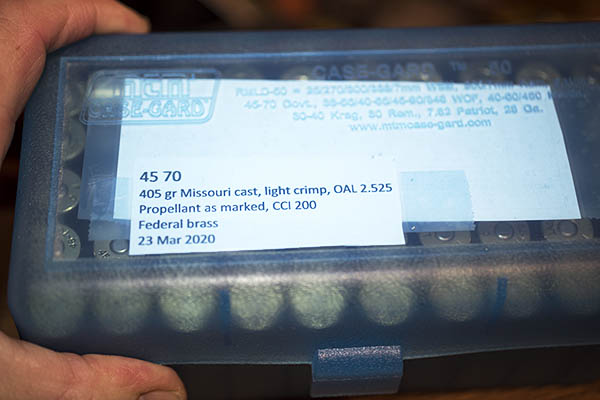

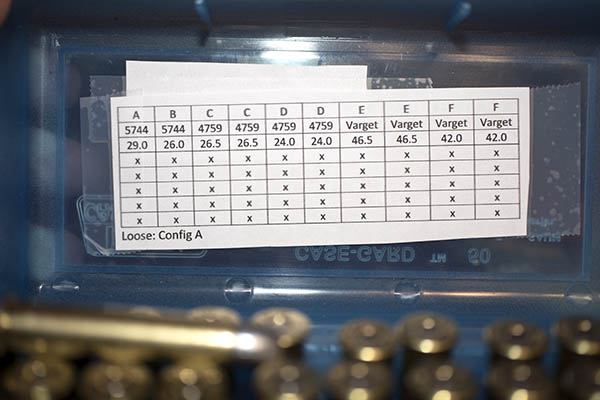

The secret sauce? It goes like this: A 300-grain Hornady jacketed hollow point bullet crimped in the cannelure, 16.2 grains of Trail Boss powder, a CCI 200 primer, and Federal brass. I don’t think the brass makes much of a difference when shooting .45 70, as long as the brass is trimmed to a uniform length. I used Federal brass because it’s what I had, and I’ve had it a long time. My .45 70 brass is over 40 years old. It’s been loaded a lot of times, but when you load at Springfield levels, brass lasts a long time.

So what’s it like to shoot the Henry .45 70 Single Shot? It’s fun. The Henry is more of carbine than a full-sized rifle, although the length of pull is the same as my other rifles and the barrel is a full 22 inches. It’s that single shot design that allows the overall package to be shorter. It’s a compact, hard-hitting package with recoil that is one thin red hair on the good side of tolerable. The rifle’s brass buttplate adds substantially to the rifle’s overall rich appearance, but let me tell you, you feel it when the hammer drops. I was glad the 300-grain bullets worked well; the 405-grain loads I had were just a hair over a tolerable recoil level for me. My shooting was all in shirt sleeves shooting off the bench, though. With a winter jacket or on a hunt, making friends with 405-grain bullets would be a lot easier.

It’s stunning just how elegant the Henry .45 70 Single Shot is, and what’s equally stunning is the amount of “cool” you get for the price. The MSRP on this rifle is $628, and Henry tells you on their website that you should expect a discount from that price. To me, the benchmark single shot rifle is Ruger’s No. 1, and that rifle is something like $1500 these days. I believe the Henry’s fit and finish are actually superior to what you get on a Ruger No. 1. The walnut on my Henry is exceptional. I think Henry is undercharging for these rifles. They’re that good.

So where am I on all of this? The Henry likes 300-grain bullets better than the heavier 405-grain stuff, and that’s where I’ll focus future load development. Several suppliers offer 300-grain .458 bullets, and there are other powders to try. One more thing I want to make sure you know: I love this rifle. Life is good. I’m having a lot of fun with my Henry.

Check out our earlier Henry Single Shot stories here:

Henry’s Home

Developing a Henry .45 70 Load: Part 2

Developing A Henry .45 70 Load: Part 1

The Henry Is In California

Henry Rifles: Made in America Or Not Made At All

Want more gun stuff? Hey, just click here!

Our rifle marksmanship blog is here!

Never miss an ExhaustNotes blog! Sign up here: