…and those two would be Ruger No. 1 single-shot rifles, arguably the classiest rifles on the planet. I smile when I hear folks talking about high-capacity magazines and black assault rifles. One shot, folks. That’s all it takes if you know what you’re doing. When you see someone hunting with a single-shot rifle, you know that rifleman knows how true sportsmen play the game.

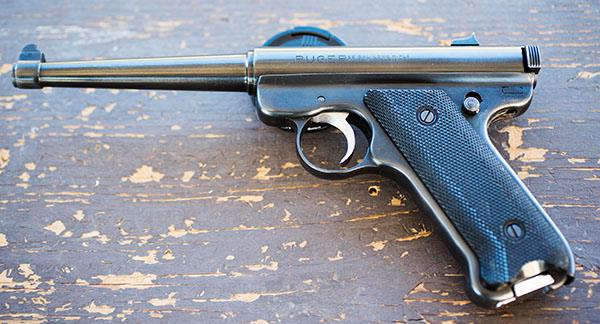

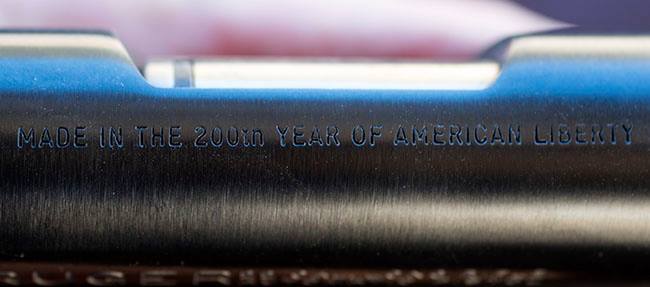

Ruger introduced these rifles in the late 1960s, and they are still in production. In 1976, like I mentioned in an earlier blog, Ruger stamped every firearm they manufactured with a “Made in the 200th Year of American Liberty” inscription. I bought my first one back then, and I’ve had a soft spot for the Ruger single-shot rifles ever since. Both of the rifles you see in this blog (mine and good buddy Greg’s) are 200th Year Rugers.

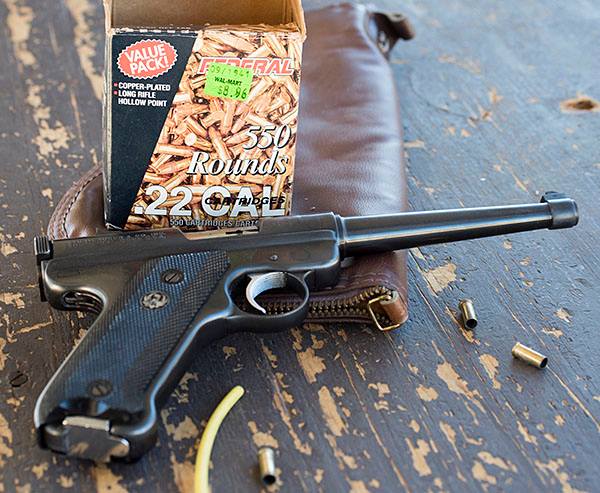

Several years ago, I found a clean, used No. 1 in 7mm Remington Magnum. I had never owned a rifle in that caliber before, and I always wanted one. I bought it and I kept it for several years without shooting it, and then good buddy Marty gave me a stash of new-old-stock 7mm Mag brass. A few years before that, good buddy Jim had given me a set of 7mm RCBS dies. With the addition of Marty’s brass, all of a sudden I was in the 7mm game. I had the rifle, the dies, and the brass.

I loaded some 7mm ammo last summer and took the No. 1 to the range. I was disappointed but not surprised that it did not group well with that first load. It takes a while to find the right load, and the load I tried that day was only the first of many. It’s okay. These things take time.

Good buddy Greg (I have a lot of good buddies) saw my No. 1 and he decided that his life would not be complete unless he owned one, too. He found one with even nicer wood than mine, and it, too, was a 200th Year Ruger. Yowwee, our load development time was cut in half! Greg was chasing the proverbial secret sauce and so was I.

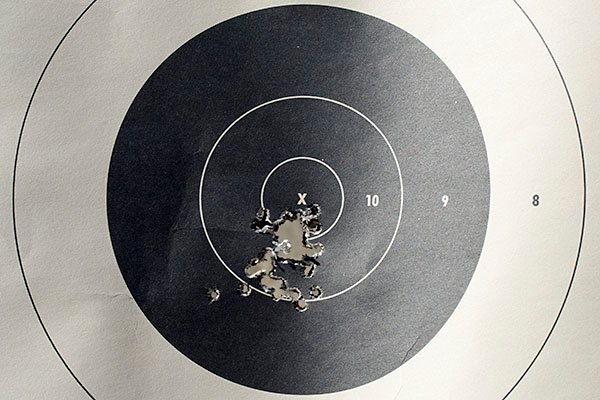

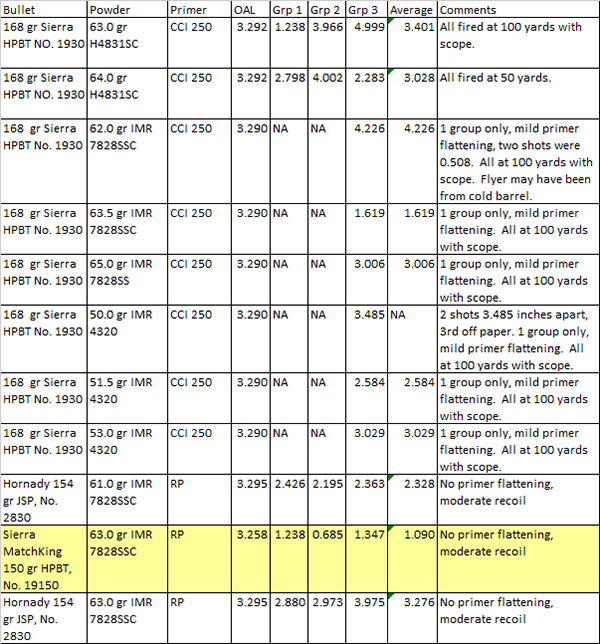

So about this load development business: Every rifle is an entity unto itself. I’m not certain what that phrase means, but I like the way it rolls off the keyboard. I think it means every rifle is different, and if that’s the case, it sure is an accurate statement. What you do when you reload ammo (what most of us do, anyway) is look for a load that delivers superior accuracy. The gold standard is getting a rifle to consistently shoot three shots into an inch at 100 yards. Most of the time, factory ammo won’t do that. You’ve got to experiment with different combinations of bullet weight, bullet design, bullet manufacturer, bullet seating depth, crimp, powder type, powder charge, primer type, and brass case manufacturer, and if you get lucky, you might find that magic MOA load (minute of angle, or one inch at 100 yards) before you run out of money for reloading components. It is amazing how much difference finding the right load can make. It can take a rifle from 4-inch groups to the magic MOA.

In the case of my 7mm No .1, I’m getting pretty close. I tested a load this past weekend that averaged 1.080 inches at 100 yards. It shot one group into 0.656 inches…

I think I’m just about there. This weekend I was using old brass with old primers, it had not been trimmed to assure consistent length, and I did not weigh each powder charge individually (I just let the powder dispenser add the same volume with each throw). Those are all tricks we use to improve accuracy. If I resize and trim the brass, use new primers, and individually weigh each charge, things should get even better. That’s the next step. Then I’ll start experimenting with bullet seating depths. I’m thinking I might get this nearly-50-year-old rifle to shoot in a half-inch at 100 yards. That would be cool.

Like I said, it took awhile to get here. Here are the loads I tried before I shot that group above….

Want to see all of our gun stories? Just click here!