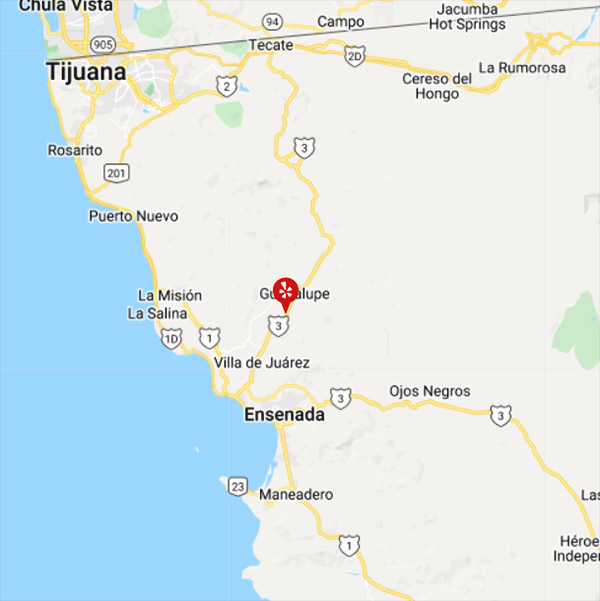

Ohio this time, folks, and today’s feature is the National Museum of the United States Air Force. We had been exploring Indiana, and Dayton was a just a short hop across the border. This was part of our great visit with good buddy Jeff, and wow, did we ever have a good time.

The official name, as denoted in the title of the blog, is a mouthful. I’ve heard of this place as the Wright-Patterson air force museum, and it’s been around for a long time. Dayton is a hop, skip, and a jump away from Vandalia, and my Dad visited the air museum decades ago when he competed in the Grand American Trapshoot in that city when I was a kid. I always meant to get here, and thanks to Jeff and my navigator’s travel planning (my navigator, of course, is Susie), I finally made it.

Dayton was also home to the world famous Wright brothers. I recently read a great book about The Wright Brothers by David McCullough, which added greatly to my understanding of their accomplishments.

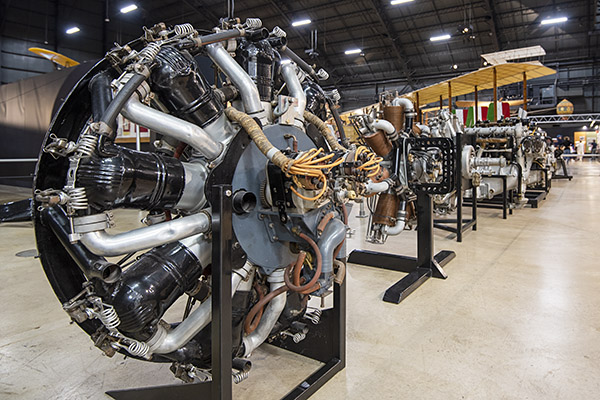

There were many other early aircraft on display. I probably should have noted what they all were. But I was having too much fun taking available light photos with my Nikon. There’s no flash in any of the pictures in this blog.

There are four main halls in the museum, each dedicated to a specific aviation era. The first is focused on the early days (that’s what you see in the photos above), and the last is focused on more modern military aircraft. There are also exhibits of presidential aircraft, missiles, nuclear weapons, and more.

The missile hall was particularly cool. The photo immediately below shows a nuclear weapon.

The missiles made great photo subjects. I had two lenses with me: The Nikon 24-120 and the Nikon 16-35. Most of these shots are with the wide angle 16-35. Both of these lenses do a great job, the 16-35 even more so in these low light, tight locations.

Here’s another photo of a nuclear (in this case, thermonuclear) bomb. It’s hard to believe that much energy can be packed into such a small envelope.

The Wright-Patterson Museum also had several experimental aircraft. These make for cool photos.

That’s Chuck Yeager’s airplane below…it’s the one he used for breaking the sound barrier (or it’s one just like it).

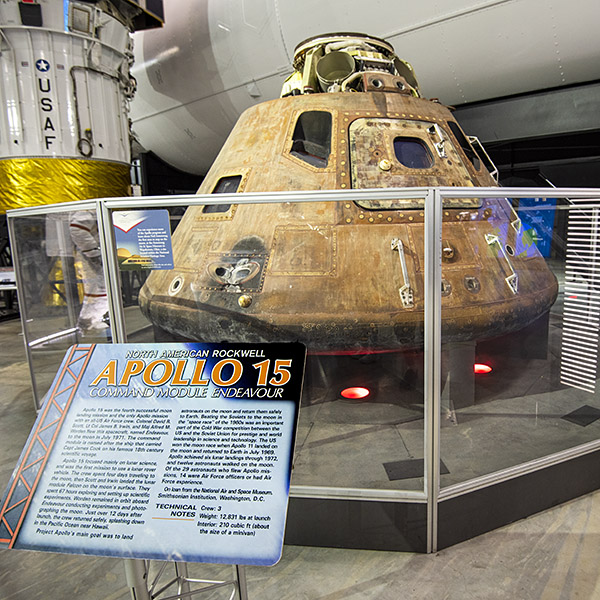

There was an Apollo display, including the actual Apollo 15 capsule.

Our tour guide told us something I didn’t know before. If the lunar landing module was damaged and couldn’t be repaired such that it could dock with the lunar orbiter, the plan was to leave the guys who landed on the moon there.

One of the displays showed an Apollo astronaut suited up for a moon walk. What caught my attention was the Omega Speedmaster in the display. There’s a very interesting story about that watch the Bulova chronograph worn when one of astronauts was replaced just prior to launch. You can read that story here. I wear one of the modern Bulova lunar pilot watches.

Here’s one of my favorite airplanes of all time: The Lockheed C-130 Hercules. It’s an airplane that first flew in 1954. Analysts believe it will still be flying in 2054. Imagine that: A military aircraft with a century of service.

A long time ago, I went through the Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia, and I made a few jumps from a C-130. My last jump was from the C-141 Starlifter jet, an aircraft that was retired from military service several decades ago (even though it was introduced way after the C-130). The C-141 jump was a lot more terrifying to me than was jumping from a C-130.

In a C-130 you have to jump up and out to break through the boundary layer of air that travels with the C-130. Because you jump up and out, it was like jumping off a diving board…you never really get a falling sensation (even though you drop more than a hundred feet before the parachute opens). On a C-141, though, you can’t do that. If you jump up and out, you’ll get into the jet exhaust and turn yourself to toast. The C-141 deploys a shield just forward of the door, so the drill is to face the door at a 45-degree angle and simply step out. When that happens, you fall the same distance as you do when exiting a C-130, but you feel every millimeter. It scared the hell out of me.

The Museum also has a section displaying prior presidential aircraft…different versions of Air Force One. That was also fascinating. One of the Air Force One planes is the 707 that was took President Kennedy to Dallas, and then returned with his body that afternoon.

Jackie Kennedy would not allow JFK’s coffin to be stowed in the freight compartment on the flight back to Washington. She wanted it to fly with her in the passenger compartment. An enterprising flight engineer obtained a hacksaw and cut away part of the bulkhead just ahead of the rear passenger door, which allowed the coffin to make the turn into the aircraft.

There were other presidential aircraft on display as well, including the one used by Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman.

Not everywhere a president flies can handle a large jet, so sometimes Presidents use small executive jets. One of the first of these bizjets used for Air Force One (any airplane carrying the President is designated Air Force One) was a small Lockheed. President Lyndon Johnson called the small Lockheed executive jet below “Air Force One Half.”

It was a good day, and a full day. Even spending a good chunk of our day at the Museum, we were only able to see two of the four halls. That made for a good day, but if you want to see the entire Museum, I think it would be wise to allow for a two-day visit.

Sign up for a free ExNotes subscription:

Are those pop up adds perturbing? Get even! Click on them and then they have to pay. And they pay us!

More reviews (museums, books, watches, cars, motorcycles, and more) are right here!