The thought came to me easily: The Patton Museum. We’d been housebound for weeks, sheltered in place against the virus, and like many others we were suffering from an advanced case of cabin fever. Where can we go that won’t require flying, is reasonably close, and won’t put us in contact with too many people? Hey, I write travel articles for the best motorcycle magazine on the planet (that’s Motorcycle Classics) and I know all the good destinations around here. The Patton Museum. That’s the ticket.

I called the Patton Museum and they were closed. An answering machine. The Pandemic. Please leave a message. So I did. And a day later I had a response from a pleasant-sounding woman. She would let me know when they opened again and she hoped we would visit. So I called and left another message. Big time motojournalist here. We’d like to do a piece on the Museum. You know the drill. The Press. Throwing the weight of the not-so-mainstream media around. Gresh and I do it all the time.

Margit and I finally connected after playing telephone tag. Yes, the Patton Museum was closed, but I could drive out to Chiriaco Summit to get a few photos (it’s on I-10 a cool 120 miles from where I live, and 70 miles from the Arizona border). Margit gave me her email address, and Chiriaco was part of it (you pronounce it “shuhRAYco”).

Wait a second, I thought, and I asked the question: “Is your name Chiriaco, as in Chiriaco Summit, where the Museum is located?”

“Yes, Joe Chiriaco was my father.”

This was going to be good, I instantly knew. And it was.

The story goes like this: Dial back the calendar nearly a century. In the late 1920s, the path across the Colorado, Sonoran, and Mojave Deserts from Arizona through California was just a little dirt road. It’s hard to imagine, but our mighty Interstate 10 was once a dirt road. A young Joe Chiriaco used it when he and a friend hitchhiked from Alabama to see a football game in California’s Rose Bowl in 1927.

Chiriaco stayed in California and joined a team in the late 1920s surveying a route for the aqueduct that would carry precious agua from the mighty Colorado River to Los Angeles. Chiriaco surveyed, he found natural springs in addition to a path for the aqueduct, and he recognized opportunity. That dirt road (Highways 60 and 70 in those early days) would soon be carrying more people from points east to the promised land (the Los Angeles basin). Shaver Summit (the high point along the road in the area he was surveying, now known as Chiriaco Summit) would be a good place to sell gasoline and food. He and his soon-to-be wife Ruth bought land, started a business and a family, and did well. It was a classic case of the right people, the right time, the right place, and the right work ethic. Read on, my friends. This gets even better.

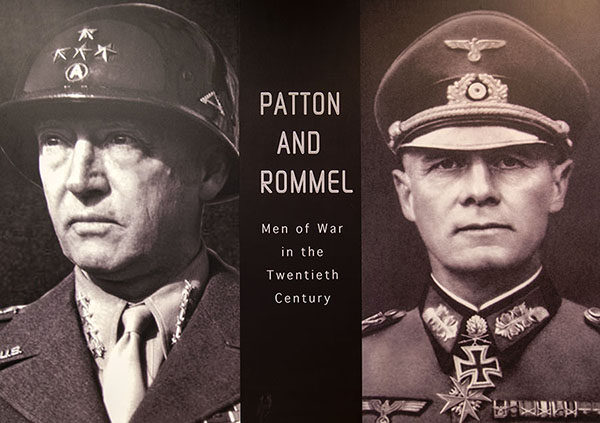

Fast forward a decade into the late 1930s, and we were a nation preparing for war. A visionary US Army leader, General George S. Patton, Jr., knew from his World War I combat experience that armored vehicle warfare would define the future. It would start in North Africa, General Patton needed a place to train his newly-formed tank units, and the desert regions Chiriaco had surveyed were just what the doctor ordered.

Picture this: Two men who could see the future clearly. Joe Chiriaco and George S. Patton. Chiriaco was at the counter eating his lunch when someone tapped his shoulder to ask where he could find a guy named Joe Chiriaco. Imagine a response along the lines of “Who wants to know?” and when Chiriaco turned around to find out, there stood General Patton. Two legends, one local and one national, eyeball to eyeball, meeting for the first time.

Patton knew that Chiriaco knew the desert and he needed his help. The result? Camp Young (where Chiriaco Summit stands today), and the 18,000-square-mile Desert Training Center – California Arizona Maneuver Area (DTC-CAMA, where over one million men would learn armored warfare). It formed the foundation for Patton defeating Rommel in North Africa, our winning World War II, and more. It would be where thousands of Italian prisoners of war spent most of their time during the war. It would become the largest military area in America.

General Patton and Joe Chiriaco became friends and they enjoyed a mutually-beneficial relationship: Patton needed Chiriaco’s help and Chiriaco’s business provided a welcome respite for Patton’s troops. Patton kept Chiriaco’s gas station and lunch counter accessible to the troops, Chiriaco sold beer with Patton’s blessing, and as you can guess….well, you don’t have to guess: We won World War II.

World War II ended, the Desert Training Center closed, and then, during the Eisenhower administration, Interstate 10 followed the path of Highways 60 and 70. Patton’s troops and the POWs were gone and I-10 became the major east/west freeway across the US. We had become a nation on wheels and Chiriaco’s business continued to thrive as Americans took to the road with our newfound postwar prosperity.

Fast forward yet again: In the 1980s Margit (Joe and Ruth Chiriaco’s daughter) and Leslie Cone (the Bureau of Land Management director who oversaw the lands that had been Patton’s desert training area) had an idea: Create a museum honoring General Patton and the region’s contributions to World War II. Ronald Reagan heard about it and donated an M-47 Patton tank (the one you see in the large photo at the top of this blog), and things took off from there.

I first rode my motorcycle to the General Patton Memorial Museum in 2003 with my good buddy Marty. It was a small museum then, but it has grown substantially. When Sue and I visited a couple of weeks ago, I was shocked and surprised by what I saw. I can only partly convey some of it through the photos and narrative you see in this blog. We had a wonderful visit with Margit, who told us a bit about her family, the Museum, and Chiriaco Summit. On that topic of family, it was Joe and Ruth Chiriaco, Margit and her three siblings, their children, and their grandchildren. If you are keeping track, that’s four generations of Chiriacos.

The Chiriaco Summit story is an amazing one and learning about it can be reasonably compared to peeling an onion. There are many layers, and discovering each might bring a tear or two. Life hasn’t always been easy for the Chiriaco family out there in the desert, but they always saw the hard times as opportunities and they instinctively knew how to use each opportunity to add to their success. We can’t tell the entire story here, but we’ll give you a link to a book you might consider purchasing at the end of this blog. Our focus is on the General Patton Memorial Museum, and having said that, let’s get to the photos.

When I first visited the Patton Museum nearly 20 years ago, there were only three or four tanks on display. As you can see from the above photos, the armored vehicle display has grown dramatically.

Like the armored vehicle exhibits, the Museum interior has also expanded, and it has done so on a grand scale. In addition to the recently-built Matzner Tank Pavilion shown above, the exhibits inside are far more extensive than when I first visited. Sue and I had the run of the Museum, and I was able to get some great photos. The indoor exhibits are stunning, starting with the nearly 100-year-old topo map that dominates the entrance.

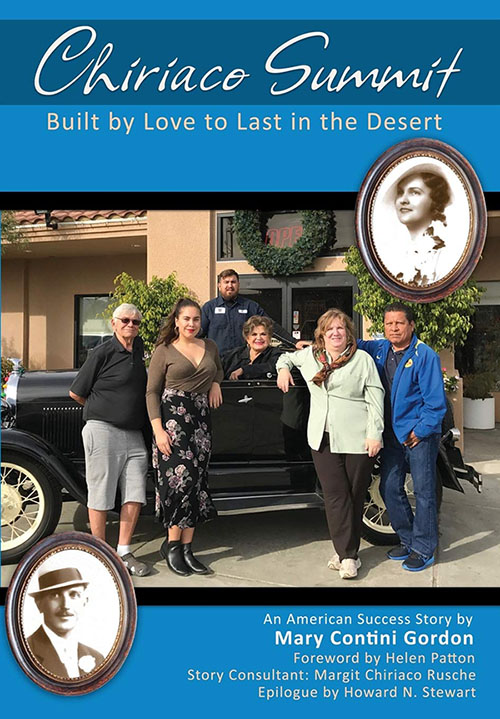

In addition to the General Patton Memorial Museum, there are several businesses the Chiriaco family operates at Chiriaco Summit, and the reach of this impressive family is four generations deep. As we mentioned earlier, it’s a story that can’t be told in a single article, but Margit was kind enough to give us a copy of Chiriaco Summit, a book that tells it better than I ever could. You should buy a copy. It’s a great read about a great family and a great place.

So there you have it: The General Patton Memorial Museum and Chiriaco Summit. It’s three hours east of Los Angeles on Interstate 10 and it’s a marvelous destination. Keep an eye on the Patton Museum website, and when the pandemic is finally in our rear view mirrors, you’ll want to visit this magnificent California desert jewel.

More great Destinations are right here!

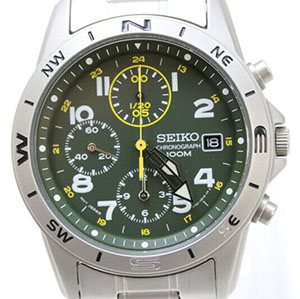

The first one I’ll mention is the green-faced, military-styled Seiko I wore on the Western America Adventure Ride. It’s a quartz watch and it’s not a model that was imported by Seiko’s US distributor (which doesn’t mean much these days; I ordered it new from a Hong Kong-based Ebay store and it was here in two days). But I like the fact that I’ve never seen anybody else wearing this model.

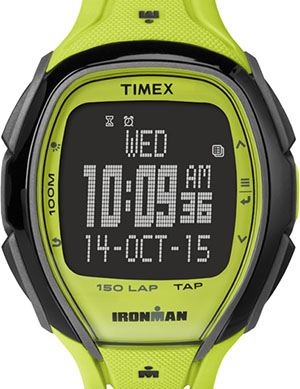

The first one I’ll mention is the green-faced, military-styled Seiko I wore on the Western America Adventure Ride. It’s a quartz watch and it’s not a model that was imported by Seiko’s US distributor (which doesn’t mean much these days; I ordered it new from a Hong Kong-based Ebay store and it was here in two days). But I like the fact that I’ve never seen anybody else wearing this model. Next up is the safety-fluorescent-green Timex

Next up is the safety-fluorescent-green Timex  The last one is a

The last one is a