This is our third and final blog on the Lee .44 Magnum Deluxe 4-die set. We posted an initial blog on the four dies and their components, and then a second blog on how to setup each die in the reloading press. This last blog on the .44 Magnum Deluxe 4-die set shows how my reloaded ammo performed and wraps up my thoughts on the Lee 4-die set’s advantages.

Keep us afloat: Click on those popup ads!

Here’s the bottom line: The Lee Deluxe 4-die set is easy to set up, it makes accurate ammo, and it positively prevents bullet pull under recoil. Lee’s locking, crimping, and decapping pin retention approaches are superior and the Lee dies cost less. It’s a better product at a lower price.

That said, let’s take a look at the specifics.

I used my Turnbull Ruger Super Blackhawk for this test series. It’s the gun you see in the big photo at the top of this blog. I fired 5-shot groups at 50 feet from a bench, using a two-hand hold and resting my hands on the bench. No other part of the revolver was supported and I did not use a machine rest. I held at 6:00 on the orange bullseye.

Superb Accuracy

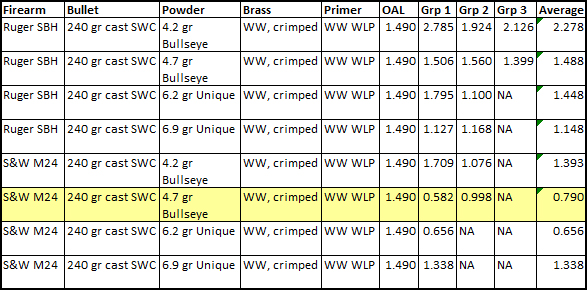

This, to me (and I imagine to most reloaders) is the most crucial aspect in evaluating any reloading equipment, and in my experience, Lee’s Deluxe 4-die set provides superior accuracy. I was more than pleased with the results. The targets below speak for themselves. My preferred .44 Magnum load of 6.0 grains of Bullseye with a 240-grain cast semiwadcutter bullet, reloaded with Lee’s Deluxed 4-dies set worked well. It was accurate, and barrel leading and recoil were minimal. I know you can load hotter .44 Magnum loads. Read that sentence again, and put the accent on you. A 240-grain projectile at just under 1000 feet per second (which is what my load provides) works fine for me.

Groups that tore one ragged hole were typical. That speaks highly of the Lee die set’s ability to produce consistent ammo.

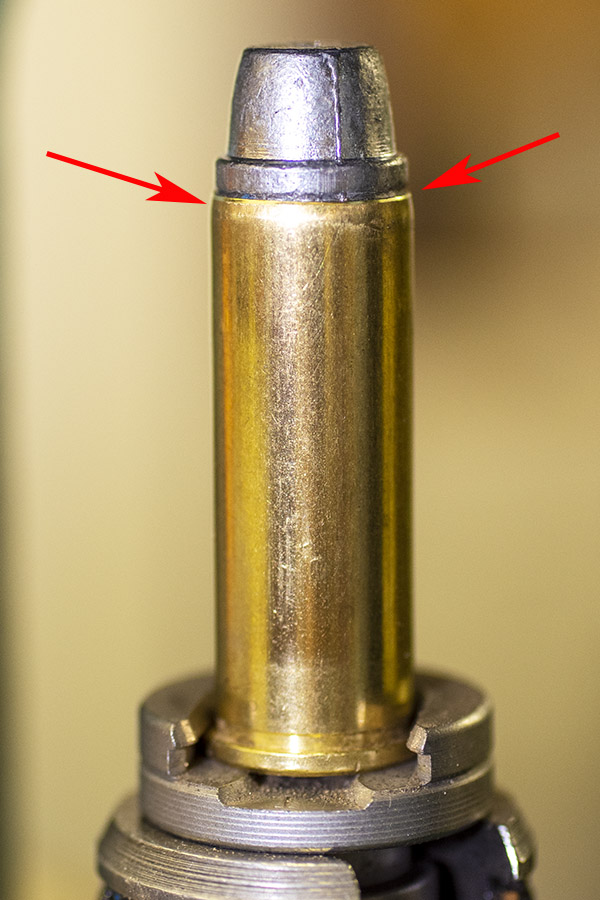

Consistent Crimping

The Lee factory crimp die is just a better approach than any other die maker’s. It gives a better crimp, it assures cartridge chambering, and I believe it maintains better bullet alignment in the case. Yeah, you can crimp in a separate step with the bullet seating die, but then you wouldn’t have the carbide straightening and alignment features you get in the Lee factory crimp die. It’s a better approach that better aligns the bullet in the case and guarantees reliable chambering.

Simply put, with the Lee factory crimp die there is no bullet movement under recoil. None of the cartridges in this test series experienced bullet pull under recoil. The Lee crimp die does a great job in locking the bullets in place. In similar testing using a Lee Deluxe 4-die set in .357 Magnum, I found that regular crimping (i.e., not using the Lee factory crimp die) allowed bullet pull, but crimping with the Lee factory crimp die did not. This .44 Magnum reloaded ammo performed similarly.

Easy Die Adjustability

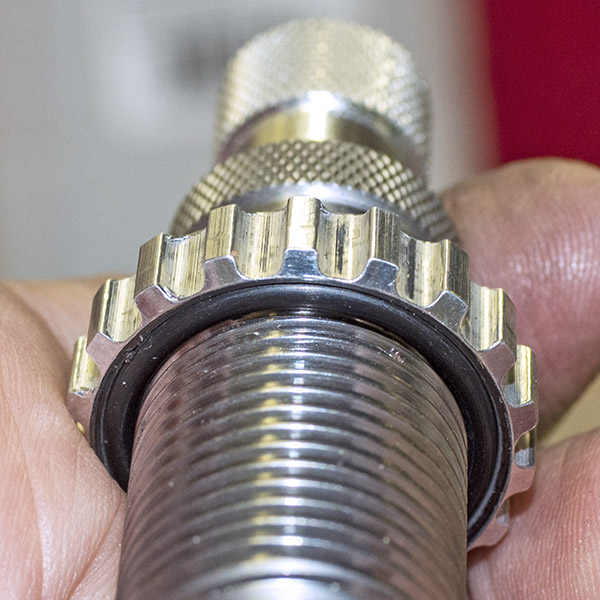

The Lee dies are easy to adjust and they stay in adjustment. I like Lee’s incorporation of orings for holding the locknut in place and for locking the die position in the press.

When I first encountered Lee’s oring approach 40+ years ago, I thought it was a bit sketchy, but I’ve come around. I believe this is better than using a standard locknut, even when the locknut uses a set screw to lock it in place on the die body. The Lee approach is easier to use. You can remove the die and preserve the adjustment without damaging the die body threads. I’ve never had a Lee die go out of adjustment, and to my surprise, none of the orings on any of my Lee dies ever deteriorated or otherwise failed (and some of my Lee dies are more than 30 years old). Even if an oring did fail, based on my prior experience with Lee Precision I’m pretty sure if I (or you) called Lee, they’d ship a replacement for free.

Free Shellholder

As mentioned previously in one of the blogs in this series, I like the fact that a Lee die set includes the shell holder.

With most (maybe all) other die manufacturers, you have to buy the shellholder separately. That’s an inconvenience and an added expense. I like Lee’s approach better.

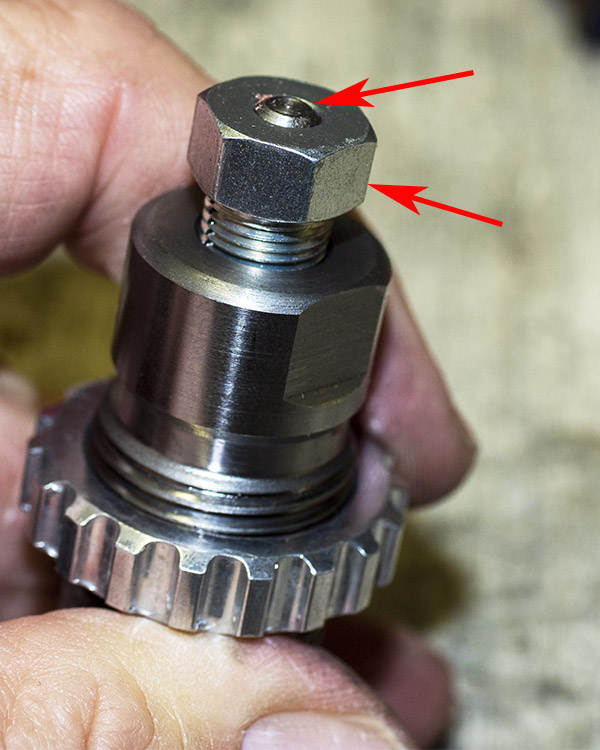

Better Decapping Pin Retention

I like Lee’s approach for securing the sizing die decapping pin better than the approach used by the other guys.

With other manufacturers’ dies, if something obstructs the decapping pin, it’s easy to bend or break the decapping pin. When that happens, a reloading session is over until a new pin is installed. With Lee’s approach, an obstruction just backs the decapping pin out of the locking collet, and if that occurs, it only takes a minute to fix.

Lower Cost

Lee dies are less expensive than other dies. Simply put, you get more bang for your buck with Lee dies.

The Bottom Line

As I said above, the .44 Magnum Lee Deluxe 4-die set is easy to set up, it makes accurate ammo, and it positively prevents bullet pull under recoil. Lee’s locking, crimping, and decapping pin retention approaches are superior and the Lee dies cost less. It’s a better product at a lower price.

Here are links to our earlier blogs on Lee dies:

Lee’s Deluxe .357 Magnum 4-die set.

Part I: Lee’s Deluxe .44 Magnum 4-die set.

Part II: Lee’s Deluxe .44 Magnum 4-die set.

Like our shooting and reloading articles? There are a lot more here!

Never miss an ExNotes blog. Get a free subscription here:

Keep us afloat: Click on those popup ads!

For more info on Lee Precision reloading equipment, click on the image below: