By Joe Berk

Here’s something different: A visit to the New Jersey State Police Museum in West Trenton, New Jersey.

I’d seen references to the NJSP Museum on Facebook and elsewhere, and being back in New Jersey a short while ago, Susie and I found ourselves casting about for things to do. Ordinarily, our visits to the Garden State include the same stops: Lunch at the Shrimp Box in Point Pleasant (awesome seafood), every once in a while a visit to Bahr’s in the Highlands (another spot for awesome food), maybe a trip to Asbury Park (think Bruce Springsteen and Danny Devito), a few of the Soprano’s filming locations, the Rutgers University campus, the Old Mill in Deans, New Hope (just across the Delaware River), and a few of our other standard stops. This time we wanted to explore a bit more, and I put the New Jersey State Police Museum on the list. I knew that it had a couple of vintage motorcycles, and I figured it would probably have a few firearms on display. Guns and motorcycles fit the ExhaustNotes theme.

The New Jersey State Police is a paramilitary, well-disciplined, and impressive organization. I’d call it a STRAC outfit (in Army slang, STRAC is an acronym derived from skilled, tough, and ready around the clock). One thing I’ve never seen is an out-of-shape NJ State Trooper.

New Jersey State Troopers are the Marines and Green Berets of the police world. That didn’t happen accidentally: The guy who formed the NJ State Police a century ago was none other than Colonel H. Norman Schwarzkopf. Not the guy who led US troops during the first Persian Gulf War in 1991 (that H. Normal Schwarzkopf was his son), but the original. Colonel Schwarzkopf was a US Military Academy graduate, and when he formed the NJ State Police, his vision was a military organization with the same look as that instilled at West Point. I’d say he succeeded.

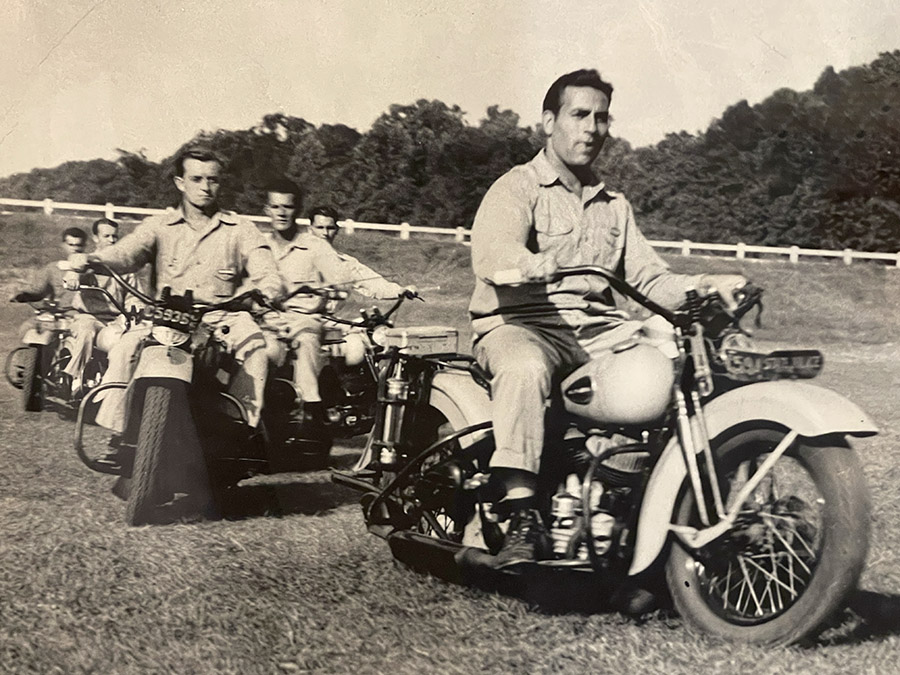

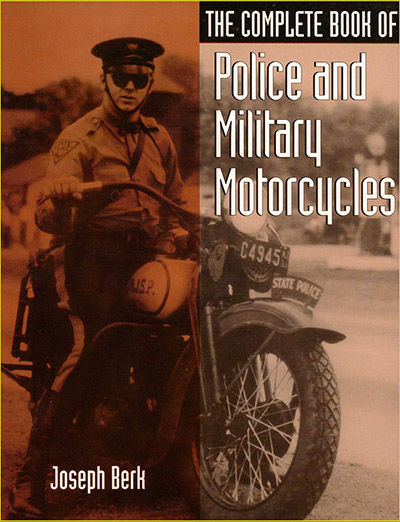

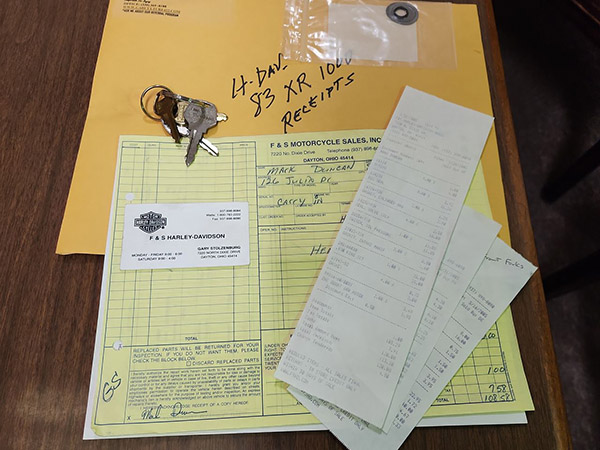

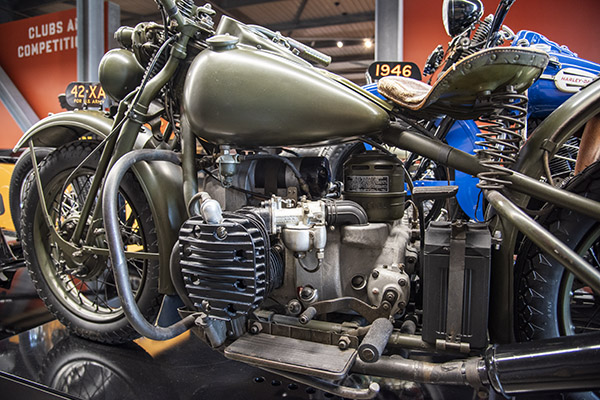

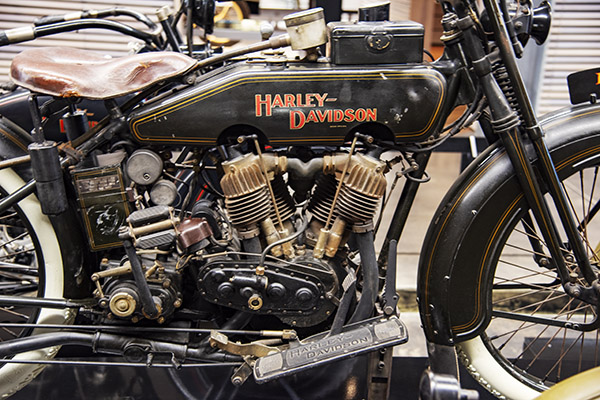

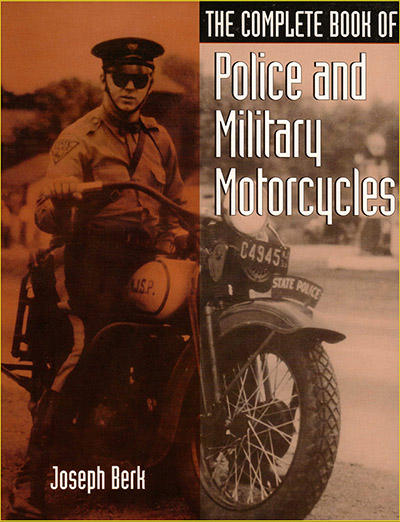

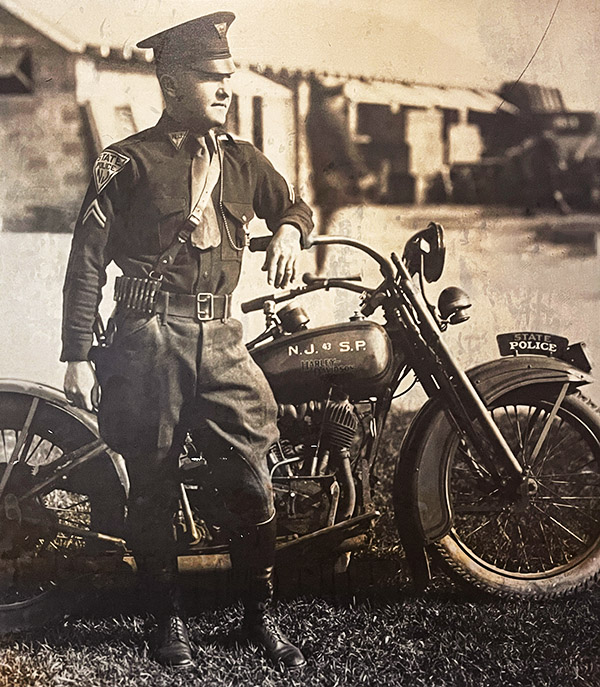

I touched on the NJ State Police when I wrote The Complete Book of Police and Military Motorcycles. The cover photo shows Captain Ralph Dowgin on a 1934 Harley-Davidson. Captain Dowgin went on to command Troop D, the NJSP branch that patrolled the New Jersey Turnpike and the Garden State Parkway. We also wrote about Jerry Dowgin, Captain Dowgin’s son and a friend of mine who owned a 1966 Honda 305 Scrambler (a bike featured here and in a Motorcycle Classics magazine story).

Getting to the NJSP Museum was relatively easy, although the location was tucked away on the NJSP Headquarters grounds. We just plugged the name into Waze, and after meandering through a bunch of small streets in West Trenton, we were at a manned gate. The location is essentially a military compound. The nice young lady at the gate called ahead to confirm the Museum was open (it was), and then she raised the gate. We followed her instructions and the map she gave to us, and we were there. We were the only visitors, so we had the place to ourselves.

The NJ State Police guns story is an interesting one.

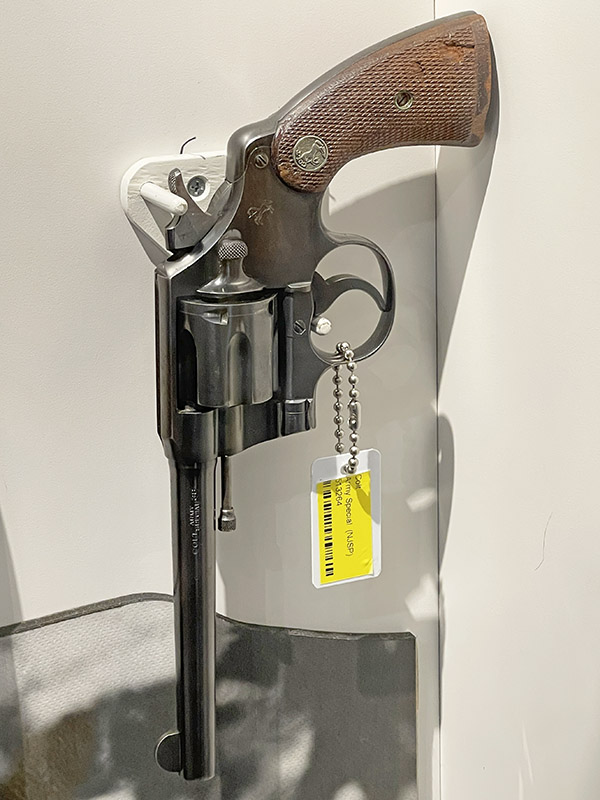

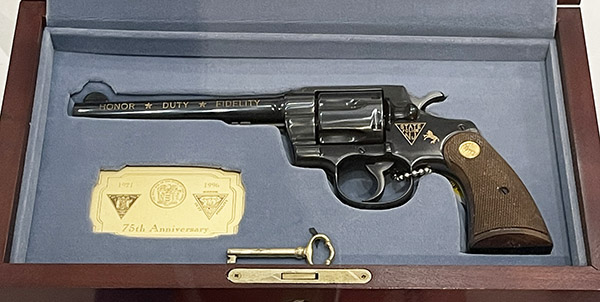

Back in the day, the NJ State Police also issued the .38 Smith and Wesson Combat Masterpiece to their Troopers, which was a 6-shot revolver with adjustable sights. This one has a 6-inch barrel. I’ve owned a few of the Smith and Wesson revolvers; they are good guns.

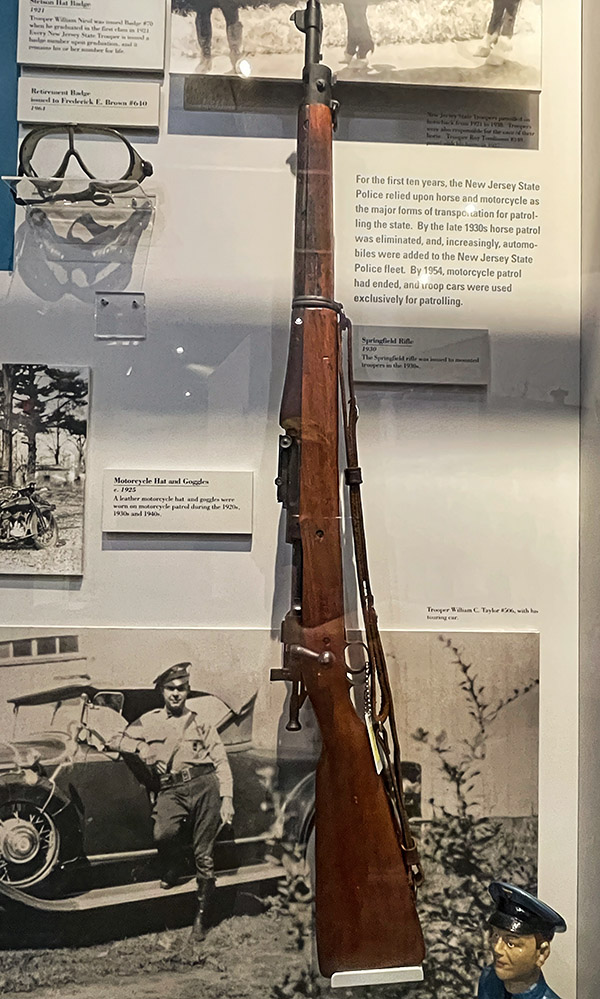

In those early days, the NJ State Police also used 1903A1 Springfield rifles. I have a 1903A1 in near perfect condition and I’ve written about shooting cast and jacketed bullets in it, and the rifle’s complex rear sight. They are nice rifles and they are collectible. Truth be told, though, I can shoot tighter groups with my 91/30 Mosin Nagant.

Later in their history, the NJ State Police used Ruger .357 Magnum double-action, stainless steel revolvers.

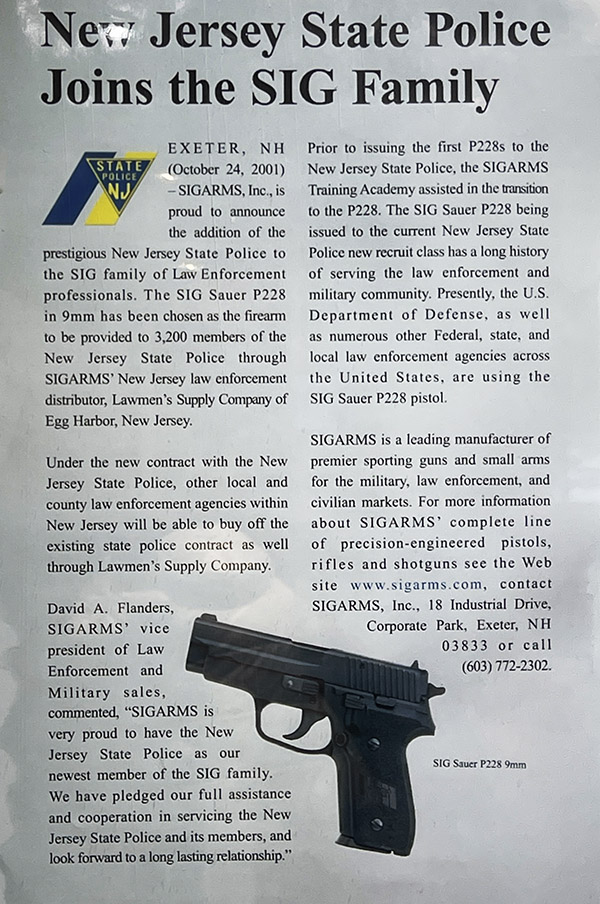

During the 1980s, many police departments made the switch from revolvers to 9mm semi-automatic handguns. Not all choices worked well for the NJ State Police. One firearm, the H&K 9mm squeeze cocker, was particularly troublesome. The NJSP experienced numerous accidental discharges. Sometime after that, the NJSP went to SIG handguns. That didn’t work out, either. When the NJ State Police made the switch to SIGs, the handguns had reliability issues, and when SIG couldn’t fix the problems, the NJ State Police sued SIG. It seemed like the NJSP couldn’t catch a break in their quest to adopt a 9mm handgun. Ultimately, the NJSP went with Glock 9mm handguns. That worked out well.

The firearms exhibits also displayed other long guns used by the New Jersey State Police.

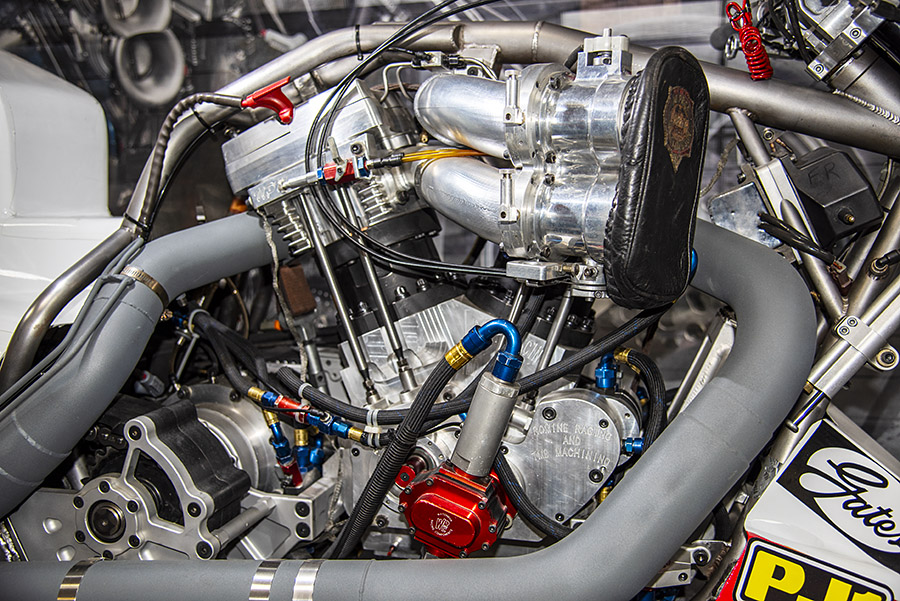

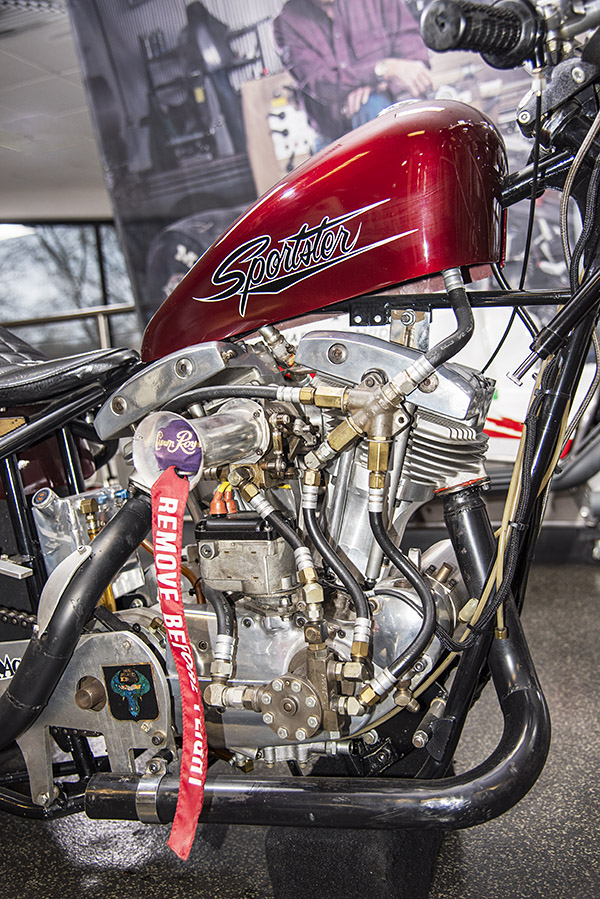

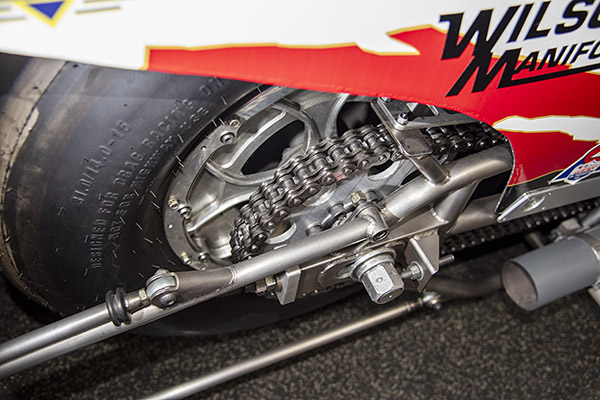

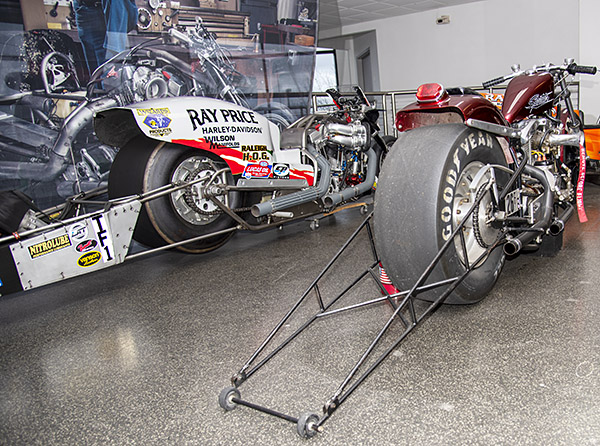

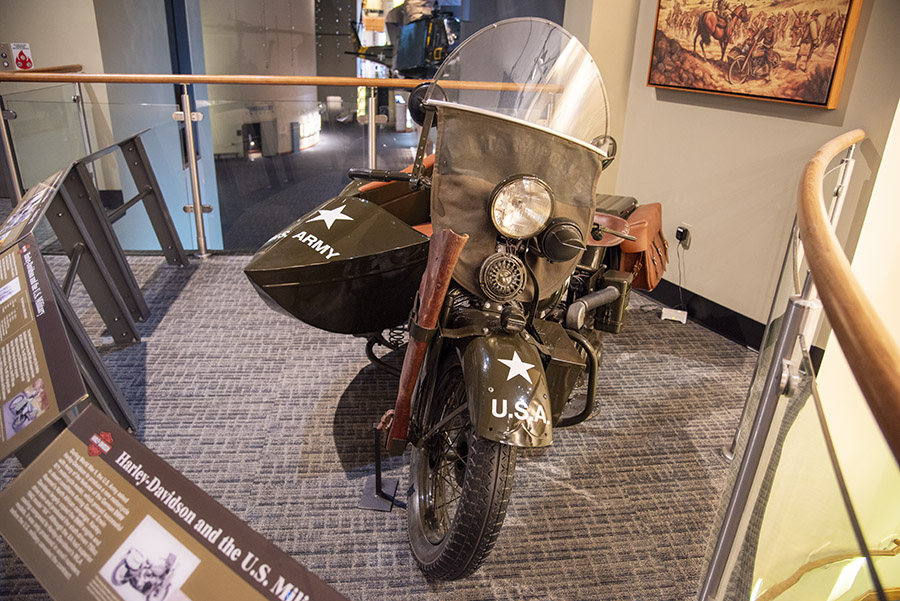

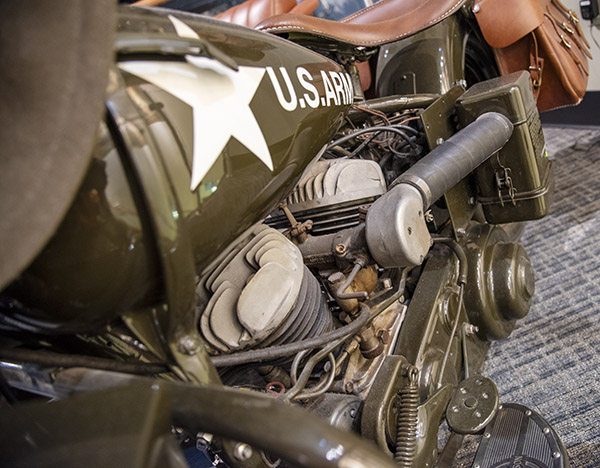

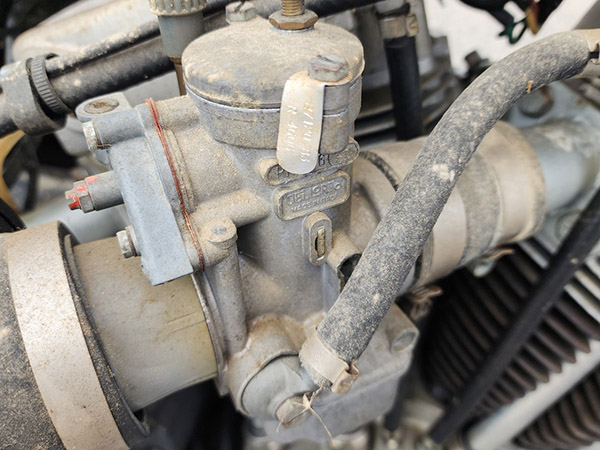

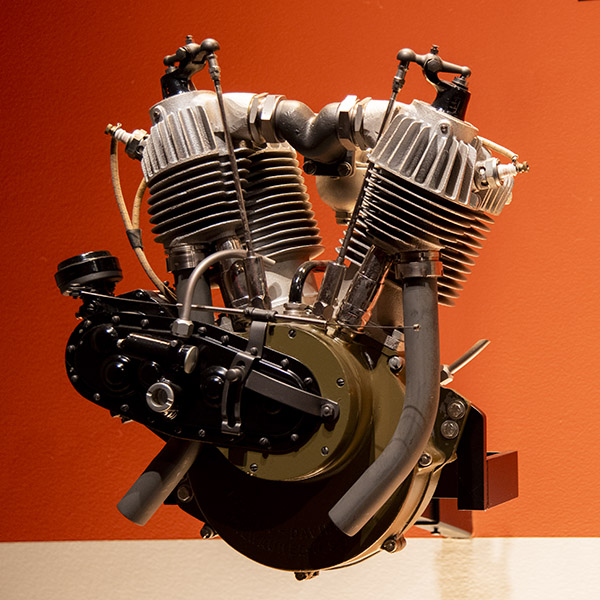

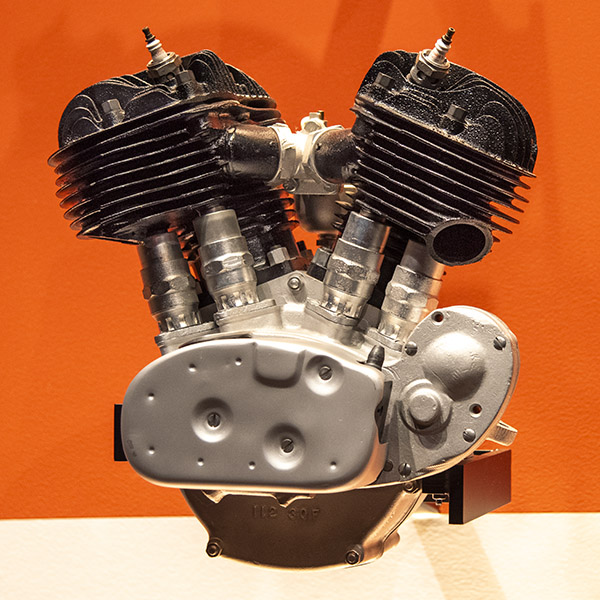

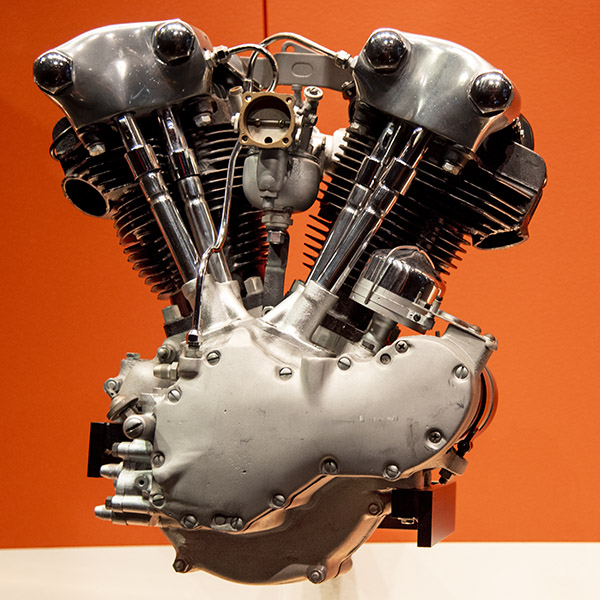

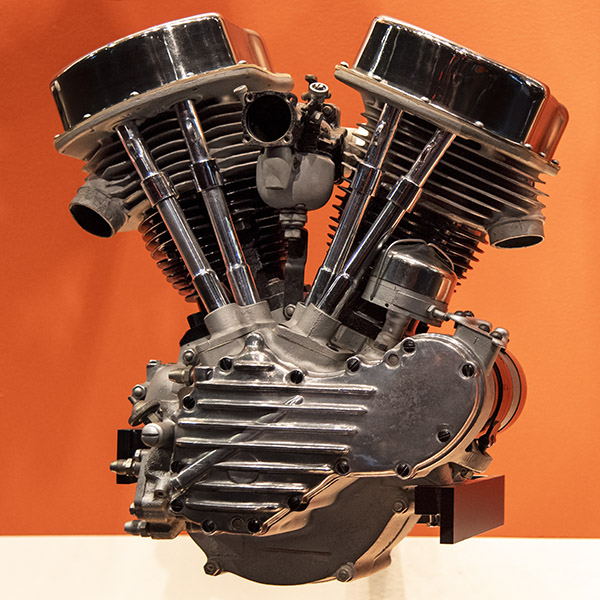

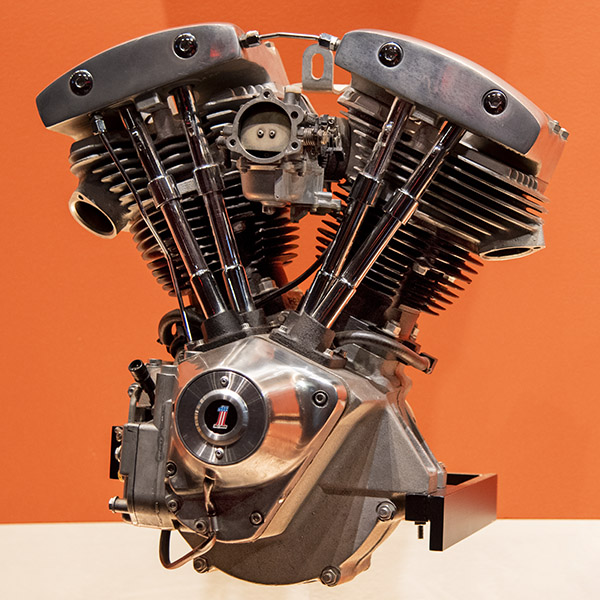

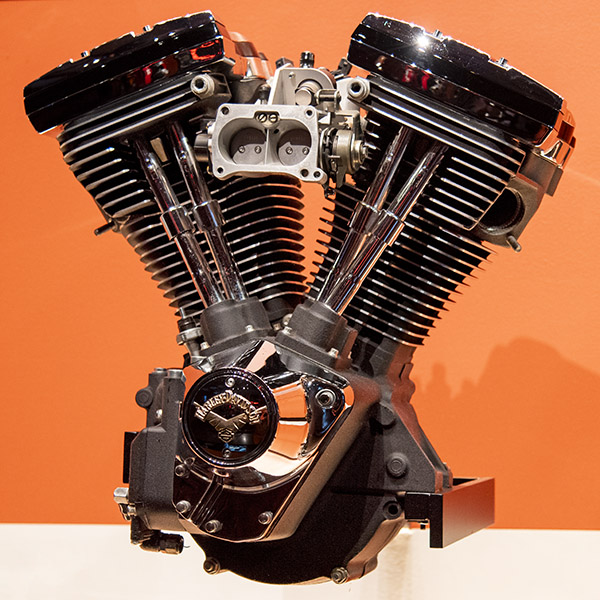

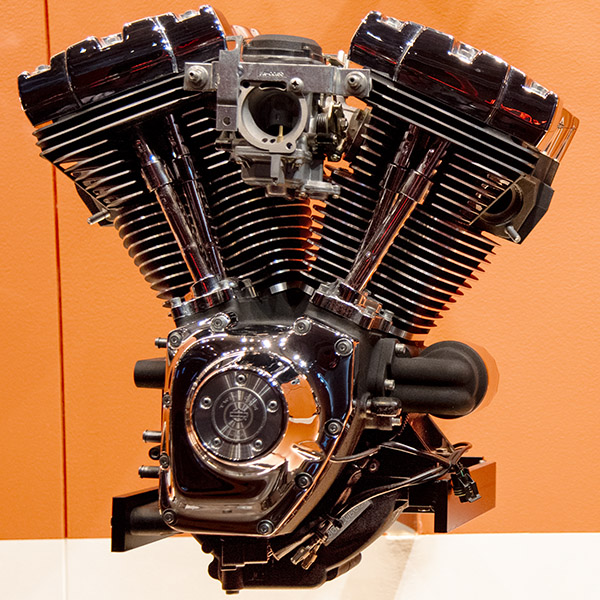

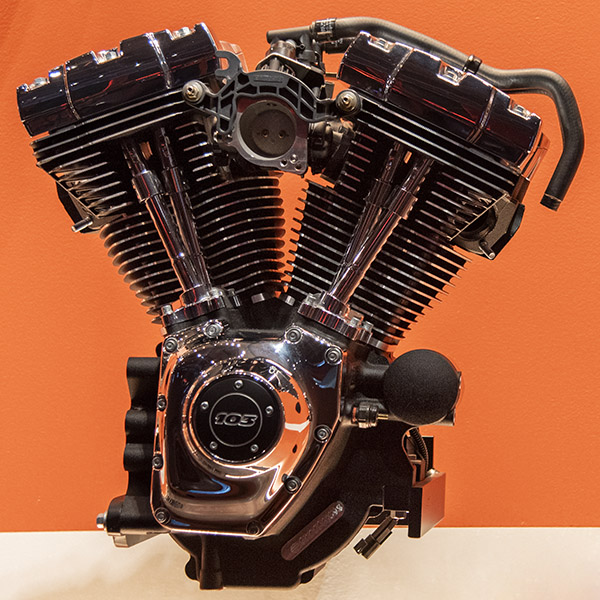

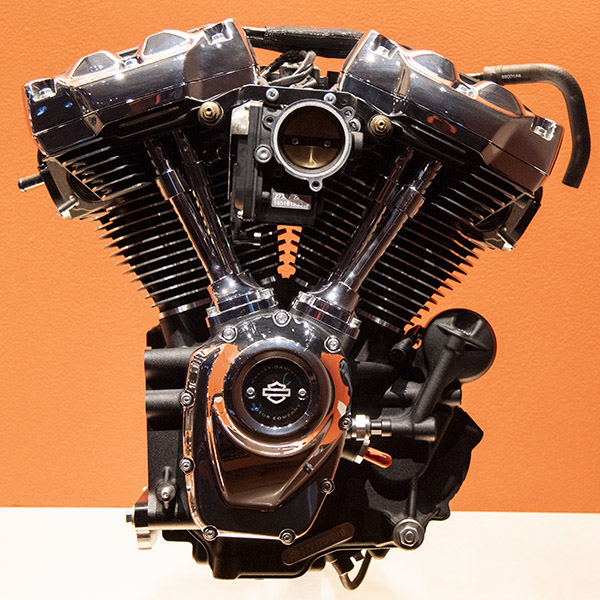

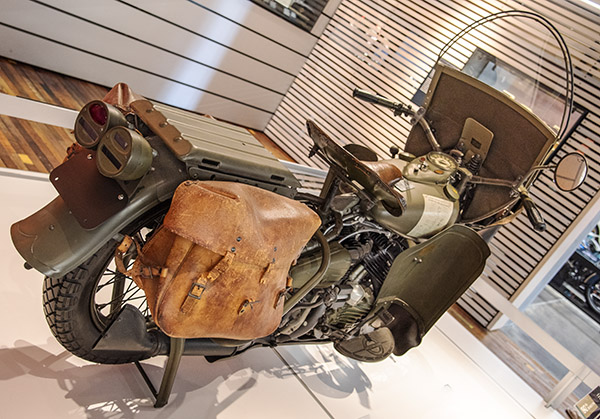

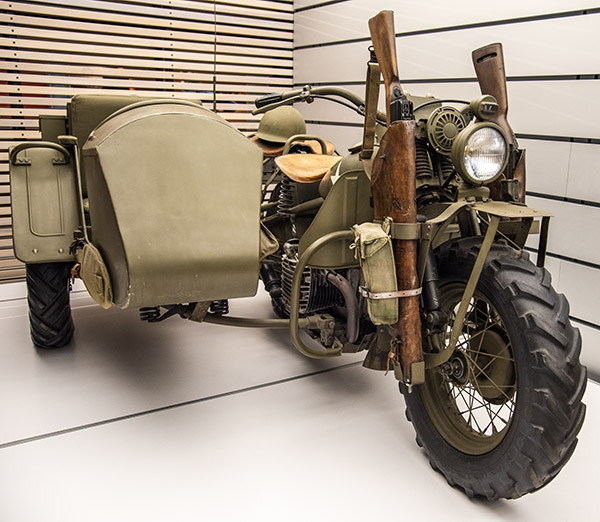

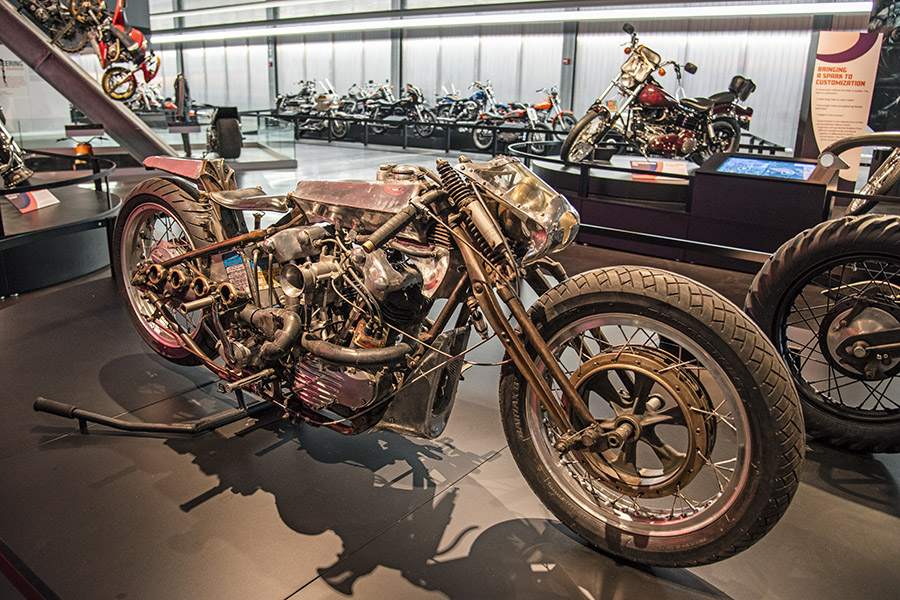

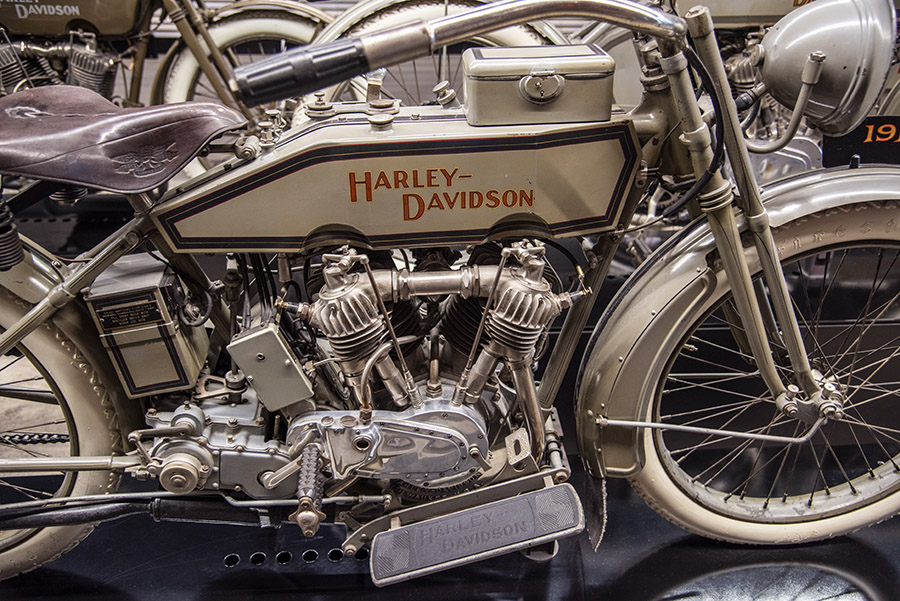

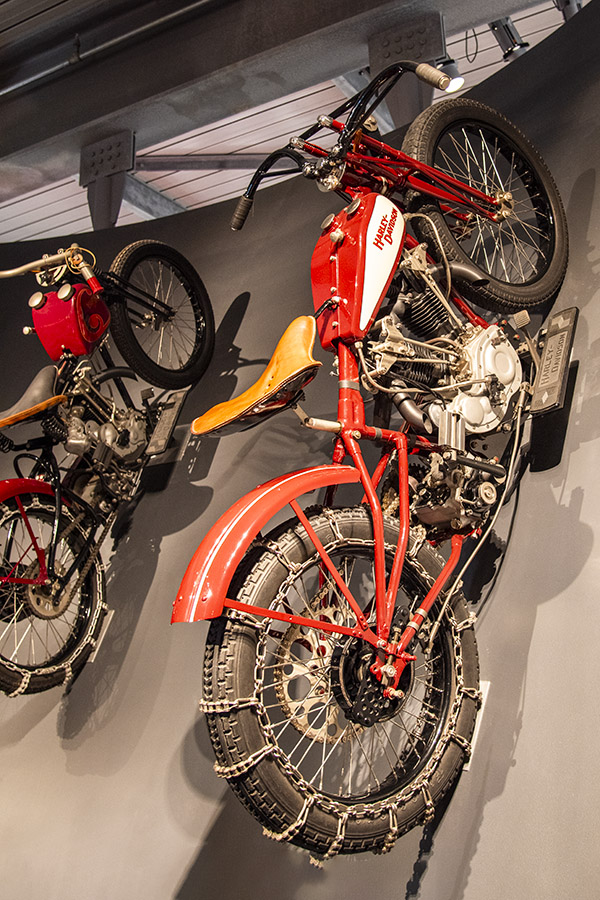

The New Jersey State Police also have a rich tradition using motorcycles, although they no longer use motorcycles for patrol duties. The NJSP has a few modern Harleys, but these are used for ceremonial functions only. In the early days, the NJSP used motorcycles year round, and in New Jersey, the winters can get cold, wet, snowy, and icy. Back in the day, the NJSP used tire chains when it snowed. That’s hard to imagine.

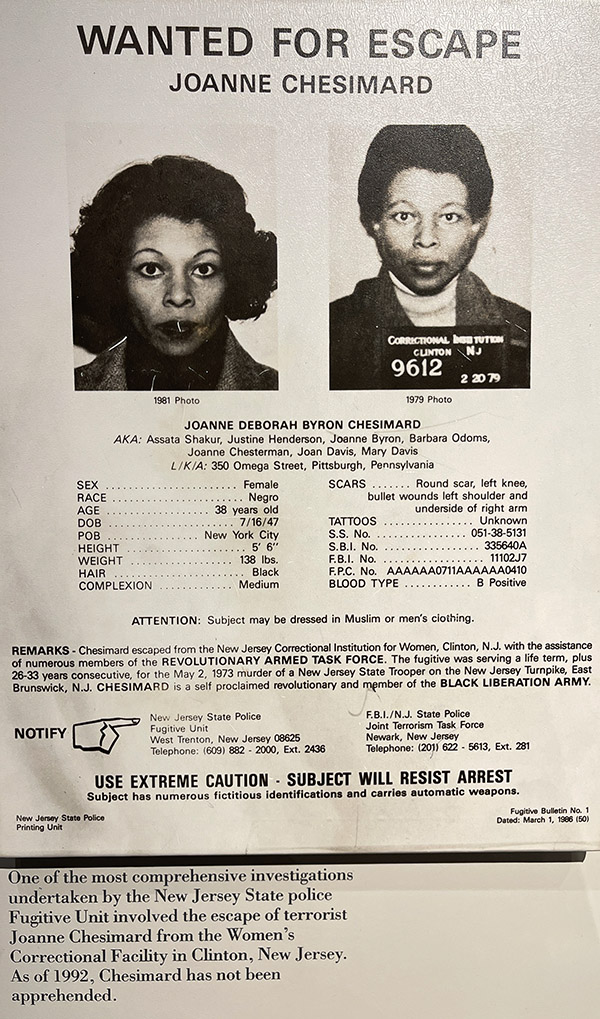

One of the NJSP Museum’s exhibits was a wanted poster for a particular person. That wanted poster is for Joanne Chesimard, who is a fugitive being sheltered by Cuba. Chesimard participated in the murder of New Jersey State Trooper Werner Foerster in May 1973. The murder occurred very near where my family lived. Another NJ State Trooper had pulled over a car driven by Clark Squire (Chesimard was also in the car). Foerster arrived in a backup patrol car. A gun battle ensued, Foerster was murdered, and Squire escaped into the woods just to the east of our home.

Squire remained at large, hiding in the woods, for several days. We thought he had escaped from the area, but police officers continued the search. Squire finally surrendered to a local police officer. We believed that if the NJ State Police had found him, Squire would not have been brought in alive (and that would have been okay with everyone I knew).

Squire, Chesimard, and a third person were convicted of murdering Foerster and sentenced to life in prison. Chesimard subsequently escaped and found her way to Cuba, where she lives in freedom to this day (sheltered by a Cuban government that refuses to extradite her to the United States). Incredibly, when Barack Obama wanted to recognize the Castro regime and lift sanctions on Cuba, returning Chesimard to serve out her sentence was not part of the deal. She remains on the FBI’s Most Wanted List to this day.

In yet another disappointment related to this Foerster murder, Squire was recently released on parole (50 years into what should have been a life sentence). I know. It’s not right.

To get back to the main topic of this blog, if you ever find yourself in New Jersey you might want to spend a few hours visiting the New Jersey State Police Museum in West Trenton. It’s free, it’s a great museum, and it’s an opportunity to learn a lot about one of the most elite police organizations in America. We enjoyed it. You will, too.

Join our Facebook ExNotes page!

Never miss an ExNotes blog: