By Joe Gresh

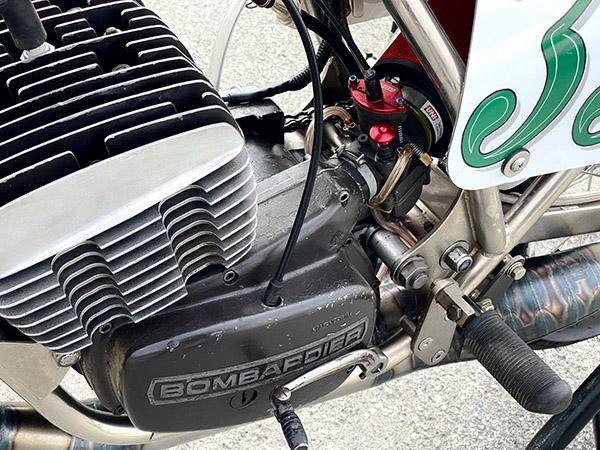

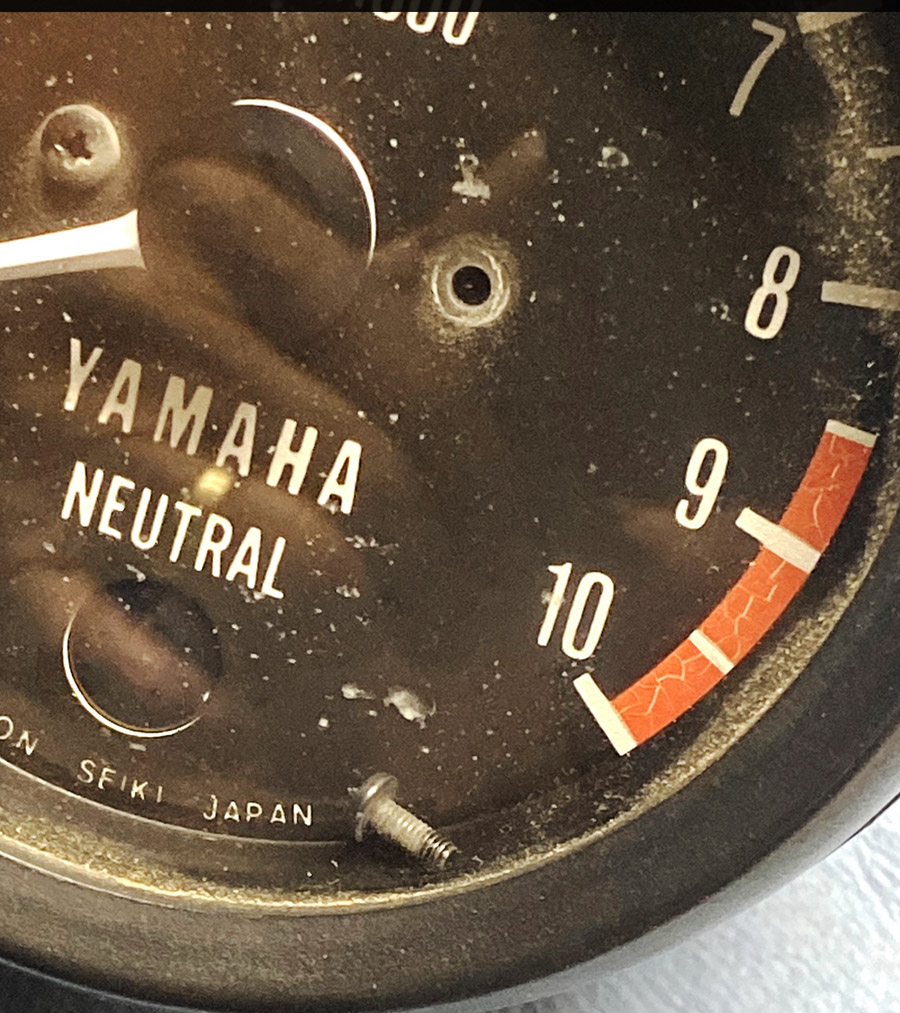

Zed has been dormant for a few years. The bike has a running issue that has eluded my best efforts to remedy. But this story isn’t about my mechanical incompetence. This story is about Zed’s gas tank.

Back in the Zed’s Not Dead series I cleaned the tank fairly well using the apple cider vinegar method. The cider/baking soda trick works well but Zed’s tank was looking a little crusty after sitting two years with alcohol laced fuel inside.

I decided to give the tank a second cider session. All went well and the tank was spotless inside. I installed the tank and filled it with fresh gas. Checking the tank for leaks revealed none so I closed up the shed and retired to dream big dreams of fun motorcycle rides to come.

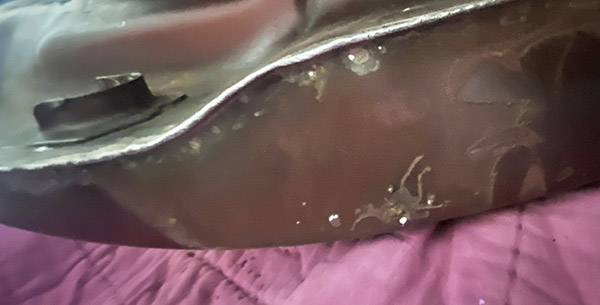

The next morning when I opened the shed a strong odor of gasoline hit my nose. Fuel was everywhere under Zed. The right side tank bottom was soaking wet. Apparently only the paint was covering pinhole rust-through spots. After draining the remaining fuel I ran a wire brush over the bottom of the tank, which revealed a ton of tiny holes.

My initial plan, because I can’t let it go, was to cut out the bottom of the tank, fabricate a new sheet metal piece to fit and then braze the new bottom into the tank. It’s a good plan and it might have worked.

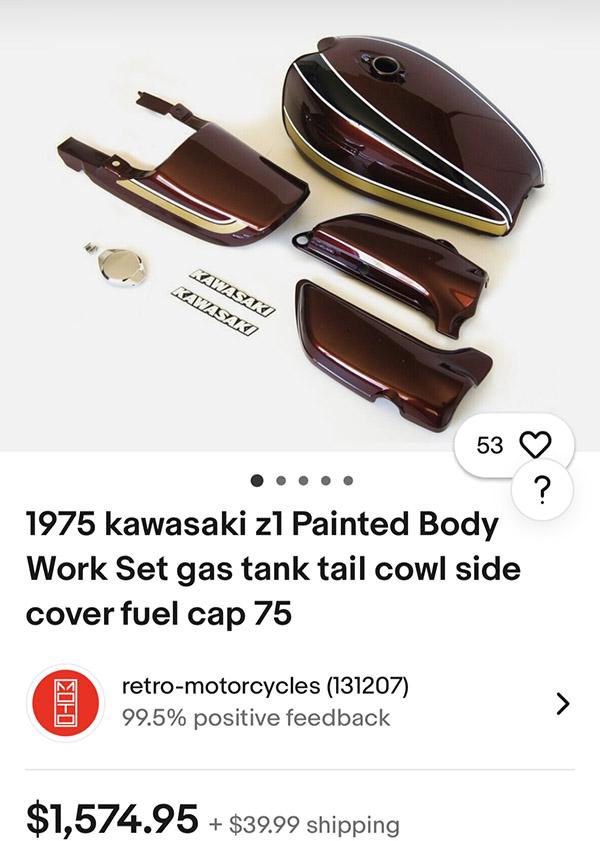

Instead, I went with Plan B: a new set of painted bodywork from Doremi (a Zed parts supplier out of Japan). Doremi is resold by several different companies in the US. I chose Cycles R Us, an eBay seller because they had the correct year and color in stock and their shipping was only $39. Prices for the body set are mostly the same (around $1500 with some outliers at $1700).

I know what you’re thinking: that’s a lot of money for a cheap bastard like me. It killed me to spend the money but used tanks are going for $500 and new, unpainted reproduction tanks are $400. Not to mention a professional paint job on my repaired stuff would probably exceed $1200.

One of the good things about the soaring value of Z1 Kawasaki’s is that you can spend money restoring them with a good chance of getting your investment back (minus your labor)

Enough of the rationalizations: let’s get into the product. Opening the well packaged box from Doremi was breathtaking. The paint is stunning. I cannot find a flaw anywhere and I don’t think the factory Kawasaki paint looked this good back when the bike was new on the showroom floor.

For 1975 Kawasaki’s Z1 had two color choices, a metallic aqua-blue that was pretty and my bike’s color, a dark burgundy that looks almost brown in low light. The color pops deep red metallic when a single photon from the sun strikes the paint surface. The stripes are perfectly applied and I cannot fault the quality of Doremi’s product.

My kit came with new tank badges and a new gas cap, some resellers break these parts out of the kit and sell them separately.

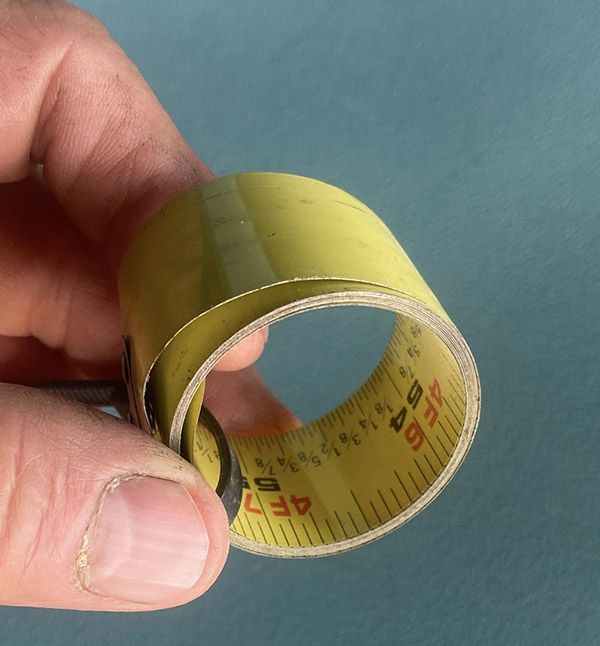

The tank badges are flat when you get them and require gentle bending by hand to fit the curvature of the gas tank. This is kind of a trial and error thing. I got the badges pretty close but they still need a little tweaking near the front. I stopped bending them mostly because I was worried about messing them up.

The gas cap comes loose in another bag. Putting the cap on was pretty easy once the roll pin was test fit into the tank.

The gas cap latch was a little harder to install. The instructions were oddly worded and there are some notches you are supposed to file into the underside of the latch. The photos aren’t super clear and I could find no reason to file notches so I ignored the instructions and did it the way I wanted.

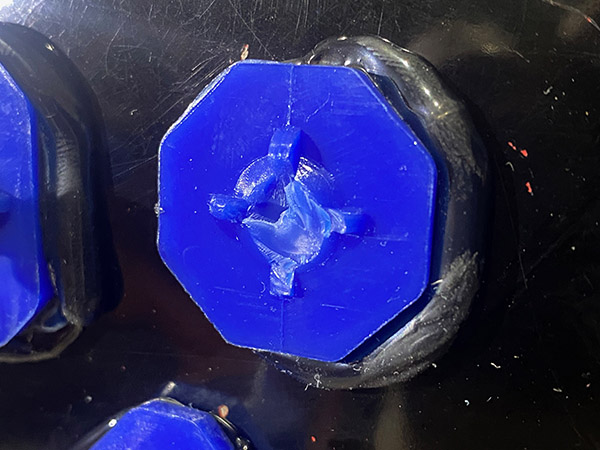

The main issue with the gas cap latch is getting the little torsion spring inside the latch then holding it concentric while the pivot shaft is slid into place. The instructions recommended using a small, flat blade screwdriver, I tried that but it was fumbly and the spring never ended up in the correct location.

The method I settled on was to compress the torsion spring and capture the two ends with a small tube (the interior metal barrel of a wire crimp connector) once you have both ends of the spring under control it’s easy to insert the spring and line it up with the pivot shaft.

The latch’s pivot shaft is sort of a rivet. After it’s in place you have to peen over the end. This is a two-man job as you’ll need to hold a weight against the pivot head on one side while rolling the other end. I’ll get CT to help me with this step.

The new side covers arrived without badges so I used the original badges. The old badges were in fair condition but I suspect the reseller removed the new badges from the Doremi kit.

The new tail section was a bit fiddley in that the bolt holes didn’t quite line up perfectly like the original tail. You reuse the original Kawasaki grommets and spacers with the new tail. Maybe new grommets would be softer and have more give. It took a little aggressive tugging to get all four bolts lined up and in place. I imagine the plastic will take a set in its new position and future fitting will be easier.

Zed’s original paint was in horrible condition, the bike had sat outside for an indeterminate length of time. Talk about patina. I cleaned up the old paint as much as I could but it was tatty and dead. The Doremi body kit transformed the bike: it looks like a new, 1975 Kawasaki Z1-B. The bike is beautiful in the sunlight with the perfectly smooth surfaces changing color as you move about. Damn, this bike looks good.

Is the Doremi body set worth $1500? If your old stuff is rusted, yes. Even if your old stuff is in good shape you’d be hard pressed to find a painter who could lay down a beautiful job like Doremi for $1500. It’s like you’re paying for a paint job and the bodywork is free!

I recommend the Doremi highly. If we had a rating system at exhaustnotes it would get top marks. If you want your Z1 to look like a new bike get the Doremi.

Never miss an ExNotes blog: