Last century I worked on a boat called the Attessa. The Attessa has worn many names since and was a steel Kong & Halvorsen dry docked at a National City, California shipyard for a fairly thorough refit. I think it was over 150 feet long by the time we added a stern section. For some reason we didn’t move the rudders aft at the same time, which was kind of weird. I always wonder if it steered well or crab-walked when you turned the helm? We also re-flared the bow to give the front of the boat a less navy, more-yachty look. A complete remodel of the interior was also done. That’s where I came in. I was one of three electricians on the job.

The other two electricians were from Montana and were sent from the yacht owner’s personal supply. The Montana boys were house electricians and had never done boat wiring so I was there to help them with the oddities of marine construction. All three of us got along well. One day I accidentally caught our lead electrician snorting coke down below in the new aft section. “I guess you shouldn’t have seen this,” he said. I didn’t care, there was so much work to do we needed everyone we could get. Besides, the painters were all speeded up. Why not Sparkies?

You may remember the Attessa as the boat featured in Goldie Hawn’s movie Overboard. The owner of the boat was an ultrarich Montana guy named Washington. The project was pretty massive. The boat even had two captains at one time. Something about overlapping contracts. I spent months just doing interior lighting. For some reason one captain of the boat hated me and would go around sabotaging my work. He bitched constantly even though I was getting more done than the other two guys put together. The other captain was fine and we worked well together.

One day Bad Captain cut out a low-voltage lighting transformer because he didn’t like where it was. I just followed the plans, man. The wires were cut at the worst location making them unusable, meaning I had to run new wires or splice them. Splicing is never good on a boat. I was pissed off. “What the F is wrong with you?” I asked the captain. “You just destroyed 8 hours of work! It was done! It was tested! Now I have to run new wires and re-do the transformer. Like we don’t have enough shit going on!”

I went to the main contractor on the project, Neil, and told him about Bad Captain’s constant needling and tampering. It caused a real hubbub. Neil was already under the gun for cost overruns and hearing about the sabotage made him mad as hell. We had a team meeting where Bad Captain was told to leave me the F alone and that if he had any problems with my work to go see Neil. We maintained a frosty relationship after that but Bad Captain let me work undisturbed.

The engineer aboard the Attessa also hated Bad Captain so naturally we hit it off in grand fashion. He was the cool kid aboard the boat. He was a lovable cad and everyone liked him, which should have tipped me off. He had a Jaguar sedan with the straight 6 and wanted to repower the car with a small block Chevy. I had a sweet, 400 cubic-inch small block Chevy trapped inside a giant green station wagon.

It was a pain in the ass to work in National City. You had to park far away and check in or out. It was like working at a factory. The shipyard had a huge floating dry-dock and did a lot of contract work for the Navy. The metal grinding was constant, every day you’d have to blow the iron dust off the decks or the next morning you’d have rust stains bleeding all over. When the new bow and stern were finished we launched the Attessa and took her to Shelter Island for completion. I was much happier on Shelter Island.

I sold the 400-inch Chevy Wagon to Attessa’s engineer for 400 dollars. He didn’t have the money right then but we were good friends, you know? He pulled the engine and transmission from the Chevy and installed it into the Jag. I guess there is a kit that makes this swap particularly easy. The Attessa re-fit job was starting to go sour. The budget was blown to hell and the owner was getting tired of shelling out so much money. In the afternoon Neil would come aboard and ask each of us what we did that day. I’d show him what I was working on and he’d tell me to speed it up as he was getting heat from the owner. Our lead electrician was fired for drug use. People were quitting. Good Captain was gone. The engineer left.

I started getting parking tickets for the Chevy Wagon. The car was abandoned without plates in downtown San Diego racking up charges. They cops traced the car to me by the VIN number. I guess the engineer never changed the title to his name and just shoved the scavenged car into the nearest parking spot. At the same time Neil was bugging me to get the old 6-cylinder Jaguar engine out of his shop. My engineer buddy had given it to me as partial payment for the small block. I had no use for the Jag engine but that didn’t deter his generosity.

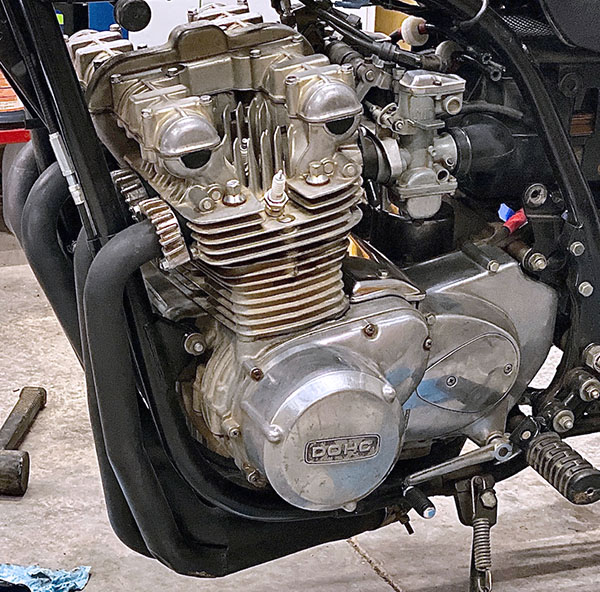

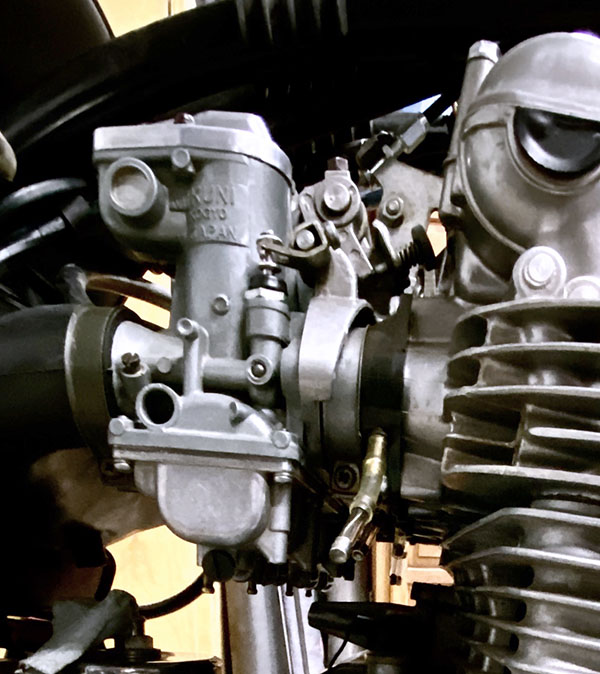

The Chevy was towed followed by more bills and notices. I had a hell of a time convincing the department of motor vehicles that I didn’t own the Chevy. The tow company kept the car. Nobody knew where my engineer buddy had gone. I had nowhere to store the Jag engine and no one wanted to buy it. This was pre-internet days and advertising the engine for sale would cost more than it was worth. I called around but even Jaguar repair shops wouldn’t give me 25 dollars for the engine. I told Neil to toss the double overhead cam, inline 6 engine in his dumpster.

Everybody on the Attessa was starting to get on each other’s nerves. It wasn’t a happy workplace since the crew stopped using drugs. There was constant bitching about how long the job was taking. On lunch break one of the welders told me, “I don’t know why they’re bitching at you, you’re the only one doing anything on this boat.” Morale was falling apart. After 5 months of hustle and push the Attessa needed a fresh team. We were burned out. I got a better offer from another boat builder (twice as much per hour!) so I told Neil I was quitting.

Neil took it well, we are still friends today, and had me use my full two-week notice to get the remaining Montana electrician up to speed as best I could. We kicked ass and when I left the lower decks were all done and we were working in the pilothouse so the electrical part was nearly finished. Starting the next boat project felt like I was in a prison early release program. The new boat build was full of happy workers. Some of the welders and painters from the Attessa got there ahead of me. It was like a family reunion except you were being paid to attend. I never got a penny for the Chevy small-block and I never heard from the engineer again. Which is just as well or I probably would have given the lovable cad another damn car.

More Joe Gresh is right here!

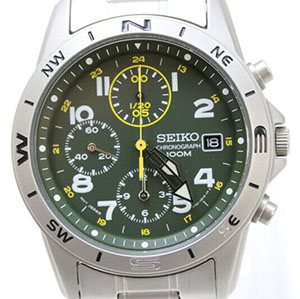

The first one I’ll mention is the green-faced, military-styled Seiko I wore on the Western America Adventure Ride. It’s a quartz watch and it’s not a model that was imported by Seiko’s US distributor (which doesn’t mean much these days; I ordered it new from a Hong Kong-based Ebay store and it was here in two days). But I like the fact that I’ve never seen anybody else wearing this model.

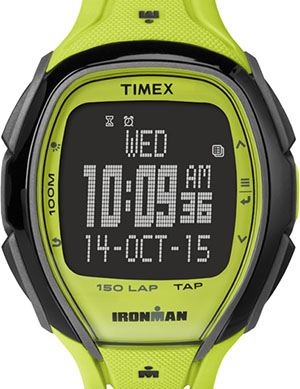

The first one I’ll mention is the green-faced, military-styled Seiko I wore on the Western America Adventure Ride. It’s a quartz watch and it’s not a model that was imported by Seiko’s US distributor (which doesn’t mean much these days; I ordered it new from a Hong Kong-based Ebay store and it was here in two days). But I like the fact that I’ve never seen anybody else wearing this model. Next up is the safety-fluorescent-green Timex

Next up is the safety-fluorescent-green Timex  The last one is a

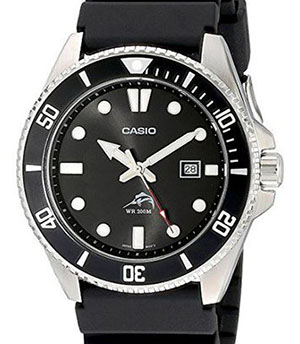

The last one is a