By Joe Berk

I went to my indoor handgun range to try the ARX bullets in two .45 ACP revolvers, my 1917 redo revolver and the 625 Performance Center Smith and Wesson. The 1917 is the one you see at the top of this blog. It’s a beautiful N-frame Smith styled to look like the 1917 US Army revolvers with a 5 1/2-inch barrel and a lanyard ring. Smith also added a nice t0uch: Turnbull color case hardening. It really is a beautiful revolver.

The 625 is a special number Smith offered about a decade or so ago. It has a custom barrel profile, ostensibly a smoother action, and better sights. It came from the Performance Center with a gold bead front sight, which I didn’t care for, so the revolver went back to Smith for a red ramp front and white outline rear sight. I thought the red ramp and white outline would be like what came on Smiths in the 1970s, but it wasn’t. The red isn’t nearly as vibrant, and the white outline is sort of a dull gray. Live and learn, I guess.

I also added custom grips to the 625 (which I refinished myself, as I didn’t care for the red, birch, and blue clown grips that came with the gun). I know this Model 625 Performance Center gun to be an extremely accurate revolver. With 200-grain semi-wadcutters and 6.0 grains of Unique, this is one of the most accurate revolvers I’ve ever shot.

But enough about the revolvers. This blog focuses on how the .45 ACP ARX bullets performed in these two handguns. Everything we’ve written about the ARX bullets has been, up to this blog, about how the bullets performed in semi-auto handguns. I shoot .45 ACP in revolvers, too, and I was naturally curious about how the composite bullets would do in those.

Here’s the bottom line:

-

-

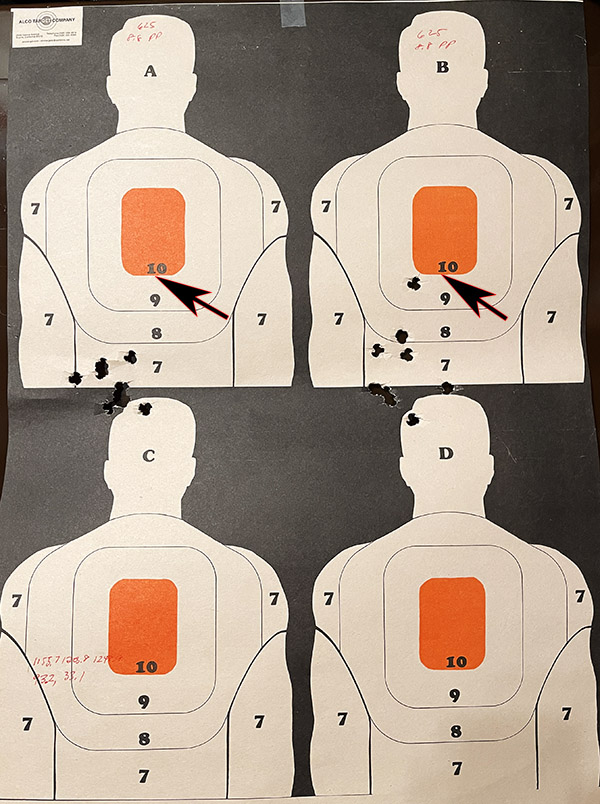

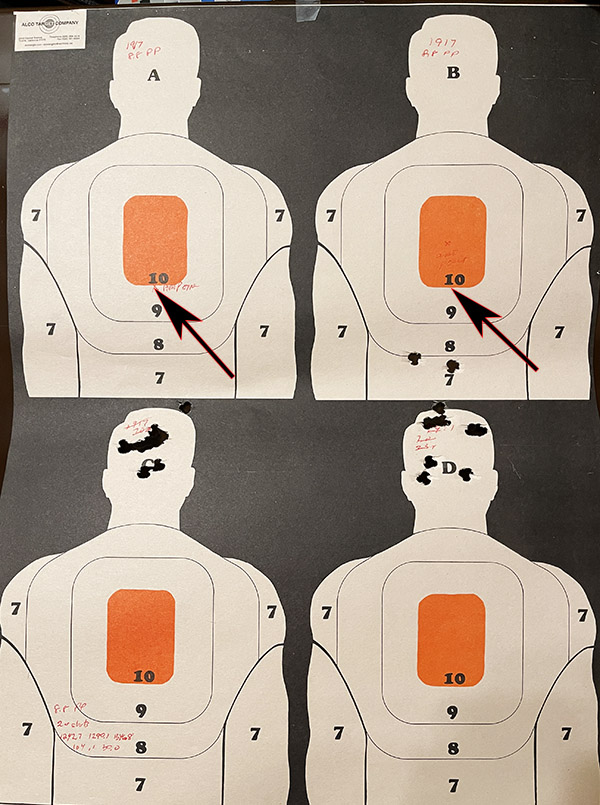

- The ARX composite bullets are not quite as accurate in my revolvers as they were in the 1911 with two different loads. The groups were good (as you’ll see in the photos below), but they weren’t as good as they had been in the 1911.

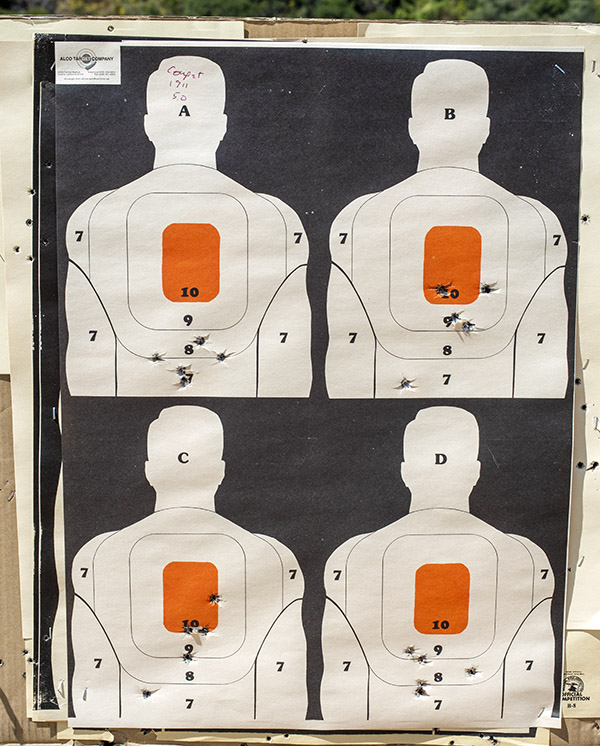

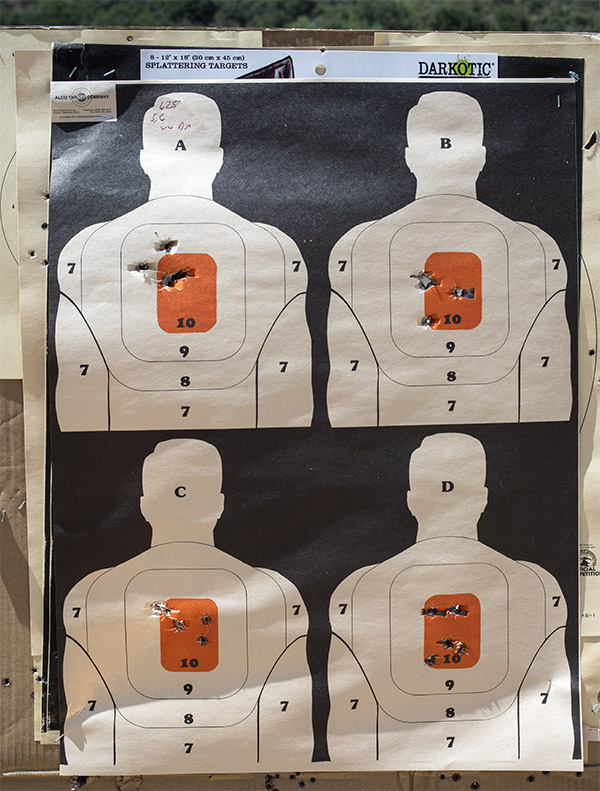

- Both revolvers shot low at 30 feet. The 625 shot about 3 1/2 inches below the point of aim. The 1917 shot about 5 inches below the point of aim. In the 1911, the .45 ACP ARX load was spot on, putting the shots right where I aimed.

-

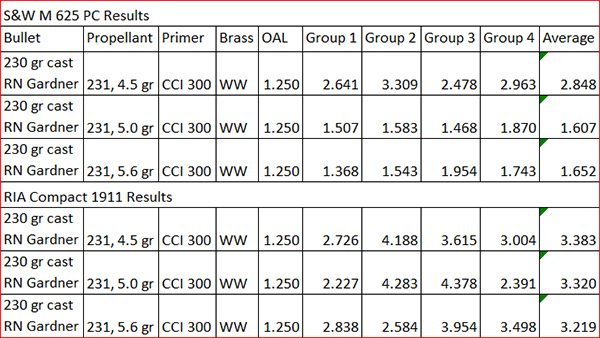

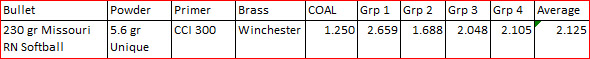

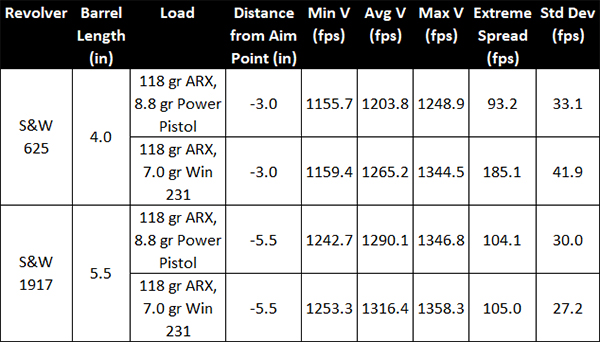

Here’s the relevant load and chrono data:

And here are the targets I shot with each revolver and the two different loads. First, the Model 625 targets:

The next two photos show the 1917 targets:

As you can see from the above data, velocities from the 1917’s slightly longer 5 1/2-inch barrel were a bit higher than from the 625’s 4-inch barrel. In the revolvers, the Winchester 231 velocities were higher than the Power Pistol loads (but not by much). The opposite was true in the 1911. Group sizes maybe were a bit better with Winchester 231 in both revolvers, but not as good as with the 1911. The 1917 has fixed sights, so my only option there is to hold higher on the target. The 625 had adjustable sights, but I don’t think there’s enough adjustment to make up for the 3 1/2-inch drop.

One more observation: Winchester 231 is a much dirtier powder than Power Pistol. I didn’t notice this with the 1911 comparisons I did earlier, but with a revolver, it’s quite noticeable.

In my opinion, the 118-grain ARX .45 ACP bullets are much better suited for the 1911 than they are for a .45 ACP revolver. That’s my opinion only; your mileage may vary.

So there you have it. This is our 6th blog on the ARX bullets, and I don’t have any more planned. I think ExhaustNotes has the most comprehensive evaluation of these bullets you’ll find anywhere on the Internet or in any of the print pubs, and I feel good about that. I like these bullets, and I really like them in my 9mm Springfield 1911, my 9mm S&W Shield, and my .45 ACP Springfield 1911. I ordered a bunch of both the 9mm and .45 bullets, and they are what I’ll be shooting for the foreseeable future.

Prior ExNotes ARX bullet evaluations are here:

25 and 50 Yard ARX .45 ACP Results

Winchester 231 and Alliant Power Pistol .45 ACP ARX Results

Dialing In A .45 ACP ARX Load

9mm and .45 ACP ARX Load Testing

ARX Bullets In Two 9mm Pistols

Join our Facebook ExNotes page!

Never miss an ExNotes blog: