Good buddy Rick C., one of the world’s great philosophers, once told me that every time he reloads he learns something new. I think he was right. This story focuses on reloading .45 ACP ammo for the Model 625 Smith and Wesson revolver, and what I learned during a recent reloading session.

The Model 625 is a beautiful revolver. It’s a direct descendant of the Model 1917 that Smith made for the US Army in World War I. The only thing I sometimes find annoying about the 625 is that sometimes reloaded 45 ACP that chambers easily in a 1911 auto won’t chamber in the revolver. This blog focuses on that issue.

There are two kinds of ammo for these revolvers. The first is standard .45 ACP, firing the same cartridge as the 1911. The other is .45 AutoRim. Firing .45 ACP ammo in a revolver like the Smith and Wesson 625 requires the use of either star or moon clips (the star clips hold six rounds; each moon clip holds three rounds). Individual cartridges clip into these. The clips provide proper headspace by holding the cartridges in place in the cylinder, and they allow the extractor to push the rounds out of the cylinder. They also work as speed clips because you can insert six rounds into the cylinder simultaneously. Theoretically, you could fire .45 ACP ammo in a Smith and Wesson revolver without the clips, but then you would need a probe to knock each case out of the cylinder. The .45 AutoRim cartridge is very similar to the .45 ACP round, but it has a rim. That eliminates the need for the clips.

Over the years, I’ve found that .45 AutoRim always chambers easily in a .45 ACP revolver. With .45 ACP reloads, however, that’s not always the case. That’s not good, as it sometimes prevents closing the cylinder. Even if you can close the cylinder with difficult-to-chamber .45 ACP reloads, the loaded cylinder will often drag on the frame, making cocking or double action fire difficult.

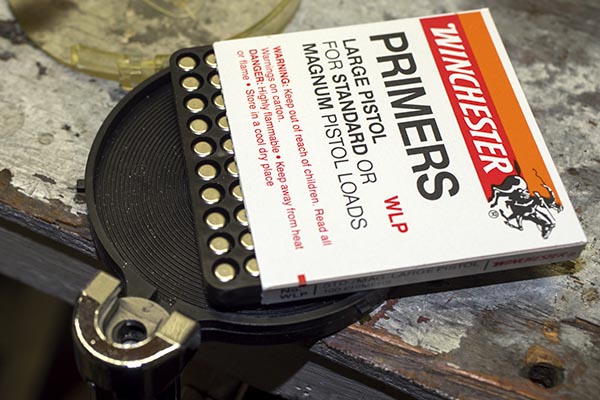

I recently loaded a batch of .45 ACP ammo that I intended to fire in my Model 625, and as is my normal practice when loading for the 1911, I put just enough of a flare on the empty cases to allow the bullet base to start into the case. After priming the cases, charging with propellant, and seating the bullets, I adjusted the seating die such that the brass just kissed the crimping ring in the seating die. At this point, I thought it would be a good idea to check the first 10 rounds in the 625 to see if they chambered fully, and you can probably guess where this story is going. A couple of rounds only went about two-thirds of the way into the chamber. I put a little more crimp on the cartridge; of the two that would not chamber, now one would and the other wouldn’t.

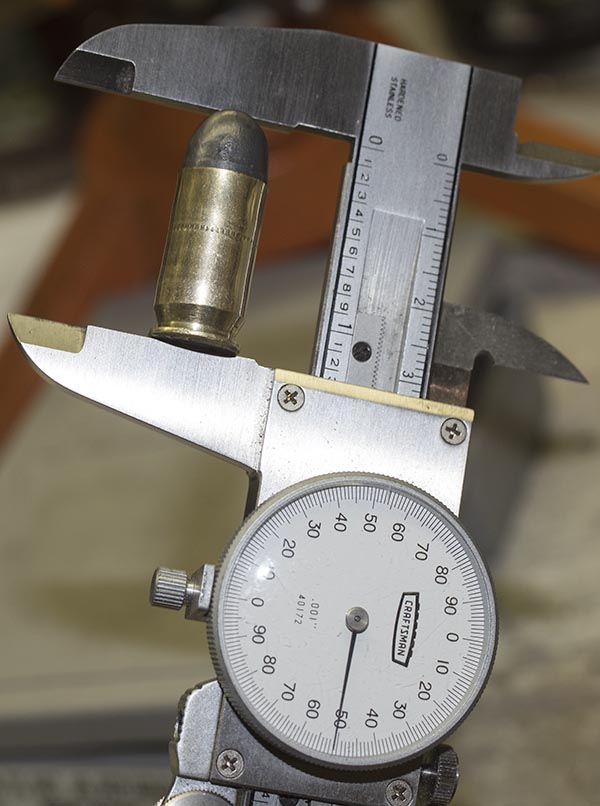

In examining the loaded rounds, I could see where the case had expanded circumferentially slightly after the bullet had been seated (it had a slight bulge at the base of the bullet. I wondered if perhaps the Missouri 230-grain roundnose bullets I was loading were just too big, so I measured them. The box told me the bullets had been sized to 0.452 inches, and that’s exactly where they were. Then I measured the case outside diameter for the loaded rounds just below the case mouth. They measured 0.475 to 0.476 inch. Then I went online to see what that dimension should be. Here’s what I found:

The drawing above is misleadingly dimensioned. The dimension we’re interested in is the 0.473 case outside diameter at the case mouth (it looks like an inside diameter on the drawing, but it’s the outside diameter. My reloaded ammo was 0.002 to 0.003 inch above this. I played around with the crimp a bit, but I couldn’t get that number to come down via crimping with my RCBS bullet seating die.

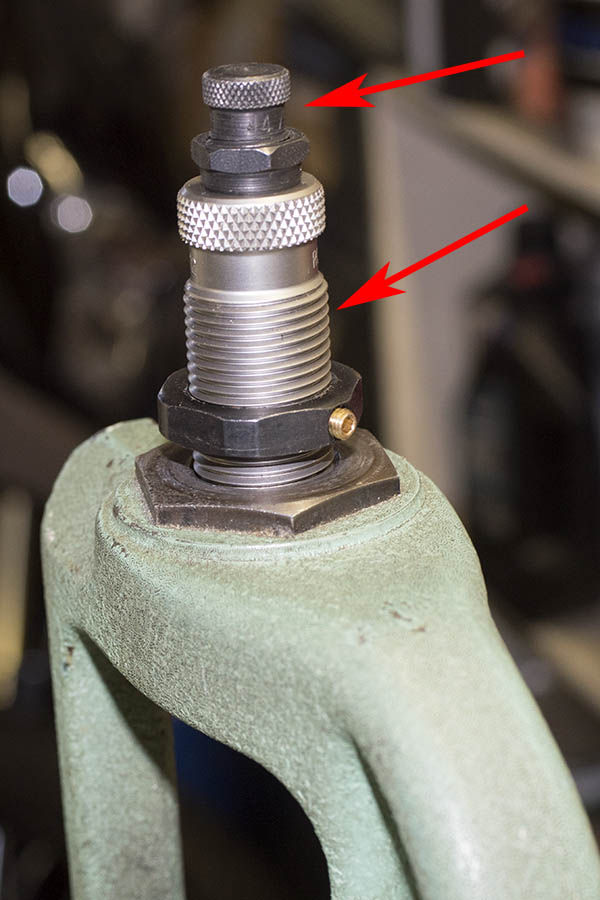

Then I had an idea. I removed the decapping pin and threaded shaft from the resizing die, and adjusted it to just kiss the loaded round a little to square up the bullet in the case and decrease the diameter at the case mouth a bit. I adjusted the depth of the seating die in the press such that I obtained a 0.473 outside case diameter result at the case mouth. The first case chambered. I then repeated the partial resize on 10 cartridges; all but one sucked right into the chamber with no circumferential play. I still had that one, though, so I played with the resizing die adjustment again until the dimension was right at 0.472, and that did the trick. It removed the flare completely, and every subsequent cartridge I loaded using this technique chambered perfectly. Basically, I was using the resizing die as a crimping tool.

It bothered me that I had to go .001 below the 0.473 inch spec to get the ammo to chamber 100% of the time in my revolver, and I was a little worried about what this might be doing to the bullet diameter. I wondered what factory ammo measures, and then I realized I had some. So I pulled it out of the ammo locker and measured it. The factory ammo measured 0.470 inch at that dimension (0.003 under the 0.473 specification), which explains why factory .45 ACP ammo always chambers so easily in this revolver. I also checked the drawing for the .45 AutoRim cartridge. It shows the case outside diameter at the business end to be 0.472, which is coincidentally exactly what I found to work perfectly for my reloaded .45 ACP ammo in the revolver.

I was a little bit worried that in running the cartridges part way into the resizing die I might be swaging the bullets to something below .451 inch (the minimum bullet diameter for this cartridge). To check on this, I measured the case wall thickness. On my Winchester .45 ACP brass (which has a wall thickness perceptibly greater than other brass I sometimes use) the wall thickness is exactly 0.010. Since my ammo measured 0.472 at the mouth after my post-load resizing/crimping operation, that should leave the bullet at exactly 0.452 inch (or 0.472 – 2*0.010). That’s exactly where it should be. The cases hold that wall thickness for some distance into the case, too. I think what the operation is doing is aligning and straightening the bullet in the case.

I’m not using any lube for my secondary resizing operation. I have carbide dies, and they do not require it.

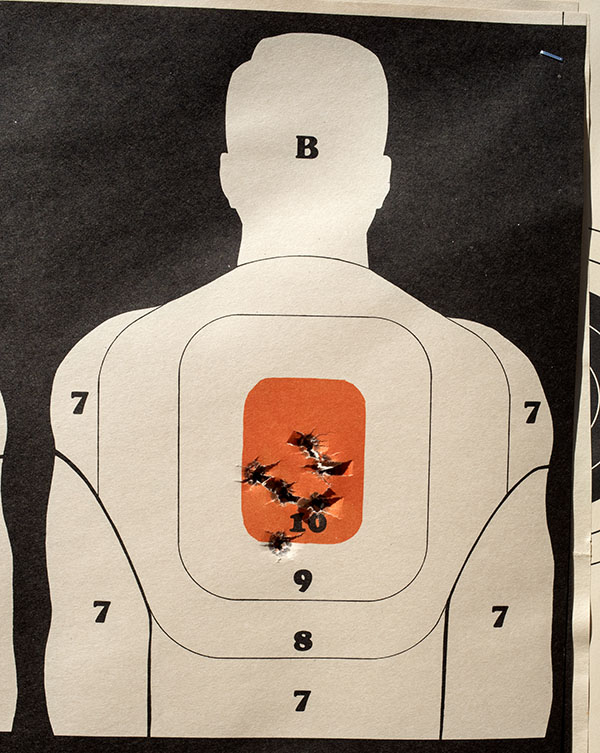

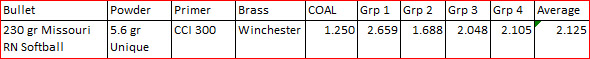

The proof on all of this was how the rounds grouped, and folks, they grouped well. It was a little windy when I fired these groups at the West End Gun Club, but the gun and the ammo did what they are supposed to do.

I like this modified approach (resize/decap, clean, prime, bellmouth, charge, seat, remove the FLRS decapper, and then crimp the ammo to 0.472 with the resizing die). It works well, it produces an accurate load, and every round chambers easily in the Model 625.

My shooting buddies Rick and Robby tell me that the Lee factory crimp die does the same thing as what I’ve described above. I ordered one for the .45 ACP and I’ll reload ammo using it, but that’s a topic for a subsequent blog.

Like what you read above? More Tales of the Gun stories are here.