By Joe Berk

Here’s a quick look at what I’ve found to be three Mosin-Nagant accuracy loads shot off the bench at 100 yards using the rifles’ standard open sights. I didn’t try to get too sophisticated for this quick comparison; I simply shot a 10-shot group with each load. All were at 100 yards. I used the NRA 25-yard handgun target because it’s what I had on hand (the bullseye on that target is slightly smaller than the 100-yard NRA rifle bullseye target, and it gave a decent aiming point). You’ll see the targets below.

My first two loads were with a rifle I use strictly for jacketed bullets. It’s my Tula 1940 round-top receiver. All you purists and keyboard commandos look away; this rifle is not for you. I refinished the stock with TruOil, I glass-bedded the action, and I reworked the trigger. As I’ve explained in earlier blogs, this rifle has a very rough bore, but the rifle remains blissfully ignorant of that fact and it shoots well.

I shot the cast bullet load in a Mosin-Nagant rifle I use for cast bullets. It’s a 1928 Ivshevsk hex receiver with a relatively clean (i.e., unpitted) bore. When I first shot this rifle with jacketed bullets, I found that it shot a foot or more above the point of aim at 100 yards with the rear sight in its lowest setting. I could have compensated for that by finding a taller front sight, but I decided instead to use the rifle with cast bullets. It shoots cast bullets within the rear sight’s adjustment range.

The Ammo

I shot 7.62x54R Russian reloaded ammo for this article. Two of the loads used jacketed bullets; the third used cast bullets.

The jacketed loads were identical other than the bullet and cartridge length: For one load, I used Hornady’s 150-grain polymer-tipped jacketed bullet; in the other, I used Privi Partizan’s 150-grain jacketed softpoint boattail bullet. I didn’t crimp either load, and I didn’t attempt to find the best seating depth. The seating depths I used, though, worked well. Both loads used a charge of 43.7 grains of IMR 4320 propellant.

The cast load used a 200-grain cast lead bullet with a gas check. I didn’t crimp the cast bullets, either, although I did use the Lee factory crimp die to remove the case mouth flare that prevented bullet shaving when the bullet was seated. This load used 18.0 grains of SR 4759 propellant.

The astute reader and reloader will notice that several of the components I used for these loads are no longer available. The Hornady polymer-tipped 150-grain .312 bullets went out of production some time ago, as did the IMR 4320 and SR 4859 powders. It’s annoying, because when I get a load that works, I’d like to be able to load it again. I’ve got a good stash of IMR 4320 and that will probably last me the rest of my life (it’s a powder that works well for .30 06 and several other cartridges). I’ve also got a good stash of SR 4759. That’s been a favored “go to” powder for cast bullet loads and reduced .458 Win Mag loads, and I’m working through it at a pretty good clip. Trail Boss and 5744 are two powders frequently mentioned as also being good for reduced loads and cast bullets, so at some point I’ll have to start developing loads with those powders. I’m probably good for the next two or three years with my SR 4759 stash.

The Results

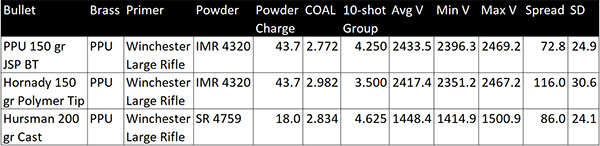

To cut to the chase, here are the loads and the results:

The Hornady polymer-tipped bullet was the clear winner:

The Hornady polymer-tipped bullet put all 10 shots into a 3 1/2-inch group at 100 yards, which is not too bad with iron sights and geezer eyes. That’s almost a 10-ring-sized group (the 10 ring on these targets is 3 1/4 inches in diameter). I’ll call it close enough for government work.

The PPU bullets are still available, although you don’t come across them very often. Sometimes the big online reloading shops (MidwayUSA, Midsouth, Natchez Shooting Supply, Powder Valley, etc.) have them on sale, and when that happens, I’ll stock up. Here are two PPU-bullet, 10-shot, 100-yard targets:

Interestingly, the velocities of the two jacketed bullets (Hornady and PPU) were about the same. The Hornady bullet had a much larger velocity spread, but it turned in the tighter group.

And finally, here’s the 10-shot, 100-yard target I shot with cast bullets:

I was pleased with the cast bullet target, too. I wouldn’t ordinarily expect a cast bullet to group as well as a jacketed bullet, but these hung right in there.

So there you have it: Three loads that return acceptable accuracy in a Mosin-Nagant.

We have several articles on Mosin-Nagant rifles and on different loads for these rifles:

Mosins, Sewer Pipes, and Lunar Landscapes

A Tale of Two Mosins

More Mosin Loads

Mosin Cast Bullet Loading and Shooting

Enemy at the Gates

Chonographing Mosin Loads

A Tale of Two Old Warhorses

Home on the Range

Stupid Hot 7.62x54R Ammo

Lee Ermey’s Guns

Revisiting World War II

Sniper!

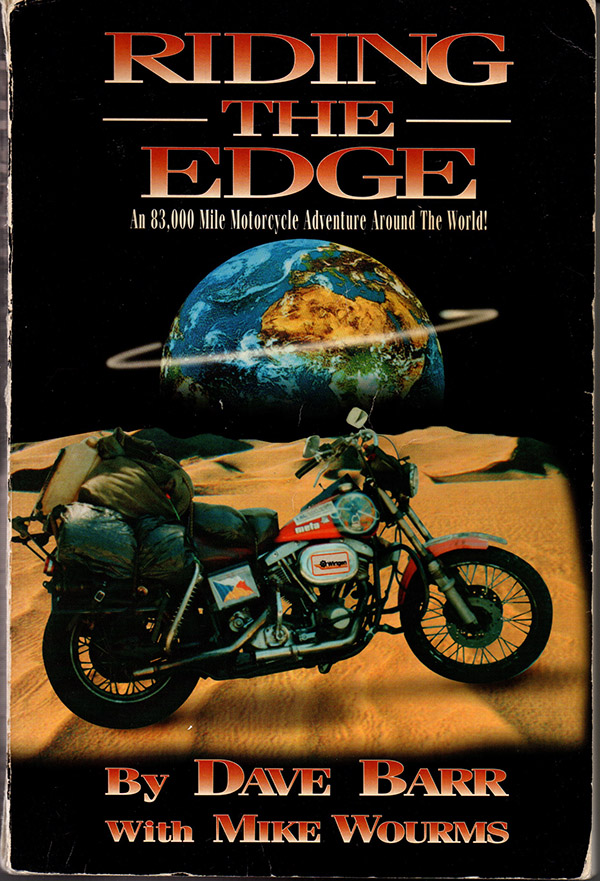

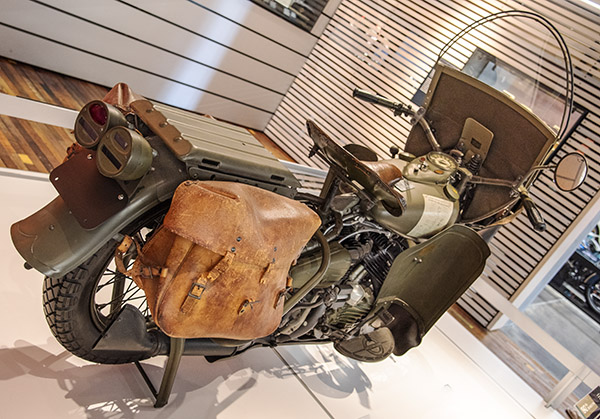

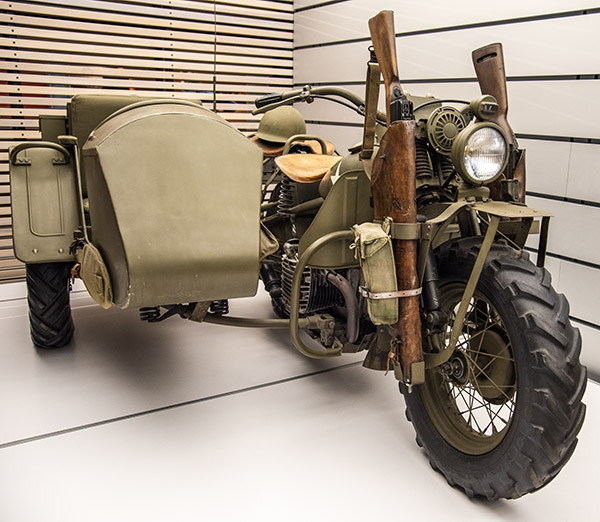

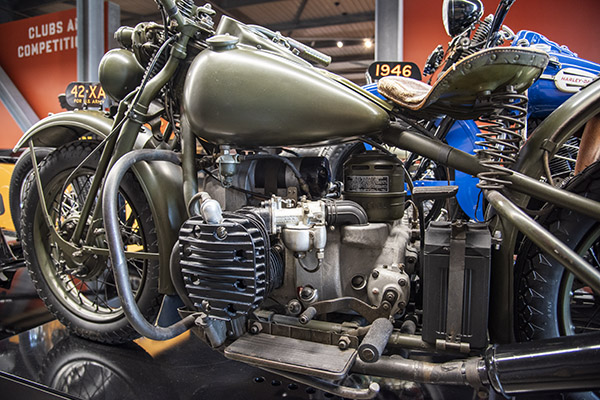

Motorcycles and Milsurps

We also have a bunch of articles on other guns (and my preferred loads) on our Tales of the Gun page.

Join our Facebook ExNotes page!

Never miss an ExNotes blog: